|

One of Mellozo da Forli's Musical Angels |

|

The Vatican Picture Gallery--the Pinacoteca | |

|

Our visit to the Picture Gallery, the Pinacoteca (from the Greek pinakes for “painted panels”). The Vatican collection of paintings began under Pius VI Braschi (1775-1799), but it was for Pius VII Chiaramonti (1800-1825) to actually found a separate Pinacoteca in the Borgia Apartments. The Pinacoteca was thereafter moved several times within the Apostolic Complex and Bramante’s corridors until Pius XI Ratti (1922-1939) built the free standing Pinacoteca Building we visit today, taking up the area north of the Square Garden.

I love the small and compact Gallery for its contents but also for its organization. You go down one long corridor, then into the large Raphael Exhibit, then turn around and come back down another long corridor to the point of beginning. And it is arranged chronologically. We begin with Giotto at the beginning of the fourteenth century and the Renaissance and end with Bernini and the Baroque in the middle of the seventeenth century—for me pretty much the beginning and the end of great art.

| |

|

We find Giotto (1276-1337) in Room II with the famous Tryptich that was made for the High Altar of old Saint Peter’s or perhaps for the Canon’s Chapel, designed to be seen by the Congregation on one side and the Canons on the other. Giotto Bondone was born in Vespignano, about fourteen miles from Florence. He was discovered by Cimabue, who saw him drawing with a stone on another stone when he was visiting Vespignano, and took him into his studio in Florence, when Giotto was just ten. Not too many years later Giotto overtook his master. His great talent lay in his ability to accurately portray nature. He “resuscitated” art, and in the words of Giorgio Vasari “he restored (art) to a path that can be called the true one.” Giotto is said to have rediscovered the “plastic values of painting” providing “concrete figurative power” with scenes that are “solid, tangible, tightly constructed, rigorous not only in the delineation, but in the expression and attitudes.” Eugenio Battisti. In Giotto there was a “spontaneous rebirth of antiquity,” and the Byzantine two dimensional other worldly expressionism was cast off. Giotto was able to reproduce every aspect of the external world, he was the master of nature. He was also the master of creating the illusion of three dimensions on a two dimensional surface. His scenes use open landscapes and architectural backgrounds to create depth. His faces are humanized and not the impassive Byzantine. His Saint Francis cycle at Assisi is the first recorded instance of a “strict application of modern geometric perspective based on lines converging toward a single vanishing point.” Eugenio Battisti. Next time you are in Assisi admire Giotto’s awesome illusionist cornices.

After Giotto painted at the Abbey, Santa Maria Novella and San Croce in Florence, he went to Assisi to finish what Cimabue had begun at San Francesco. Pope Boniface VIII Caetani (1294-1303) learned of Giotto’s work, and sent a prelate to see him. The prelate asked Giotto for a drawing he could take to the Pope, and Giotto took a sheet of paper and a pencil dipped in red, and resting his elbow on his side, with one turn of the hand he drew a perfect and exact circle. The prelate was not satisfied that this simple circle would please the pope, but Giotto would provide no more. The prelate explained to Boniface how Giotto had made the drawing, and the pope quickly perceived Giotto’s talent. Today, the drawing is known as “the perfect O of Giotto,” and it is memorialized in the Italian proverb used to describe dull people—“Tu sei piu tondo che l’O di Giotto:” “You are rounder than the O of Giotto”: the Italians make use of the double entendre of the word tondo—slowness of intellect and an exact circle.

Boniface summoned Giotto to Rome, where he made the famous Mosaic of the Navicella for old St. Peter’s (the remnant of an angel from the Navicella is in the Vatican Grottoes), and several frescoes in the church, now lost, and frescoes for the loggia of the Lateran, of which the fresco on the pillar in the nave is the sole surviving piece. The Tryptich, tempera on wood, was made some time early in the fourteenth century by Giotto and his assistants (he now had a scuola), and perhaps after 1315, since Pope Saint Celestine V (1294) is included on one of the panels, and he was canonized in 1313. The donor of the work was Cardinal Jacopo Caetani degli Stafaneschi, nephew of Boniface. It adorned the high altar at St. Peter’s, perhaps later moved to the Sacristy of the Canons. When new St. Peter’s was built the Tryptich we now see in the Pinacoteca somehow managed to survive, probably because of the sanctuary of the Canons.

|  | |

We are able to get as close as we want to the Tryptich, as it is covered with a very thin layer of glass, almost invisible. It is one of the wonderful things about Rome: we are able to get so very, very close to stupendous works of art. The Tryptich is one of my favorites because I am able to place myself so close to one of the men, perhaps the man, who began the Renaissance in painting over 700 years ago. And close you should get, as the work is magnificent, full of color, and the figures full of life, the subjects at the center of our Faith.

On the front side, which would have faced the congregation, we have Peter enthroned, holding the keys, with saints presenting Cardinal Stefaneschi and then we think Pope Saint Celestine (recently sainted and thus with the halo). The cardinal presents a small model of the Tryptich, which is withing a larger structure, probably the structure in which the Tryptich was held on the high altar of old St. Peter’s. Celestine holds a scroll, query what it contained. Saint George presents the Cardinal and I can’t identify the saint who introduces the Pope, can you? Let me know! Again in front of the throne is a perspectival geometric floor. The throne bears the Cosmati and Gothic marks of the kind Arnolfo used for his tombs and baldacchinos. Andrew, John the Evangelist, Paul and James are in the side panels. Only the left panel in the predella survived, it holds three saints, one of whom is Saint Stephen.

|  | |

On the back, or the side which would have faced the Canons, Jesus is enthroned, with Cardinal Stefaneschi in layman’s robes at his feet, angels surrounding Our Lord, who sits in a two staired baldacchino of the type Arnolfo made at San Paolo, and which Giotto would certainly have seen. In the foreground is a pavement where Giotto exhibits his skills in perspective. Giotto spent some time with the concept of the vanishing point, a precursor to Brunelleschi’s work. The baldacchino also has Cosmati elements like Arnolfo’s. In the side panels are the Crucifixion of Peter and the Beheading of Paul, put into their historical place, Peter “inter duas metas” or between the two meta of the Pyramid of Celtius (once known as the Meta of Remus) and the Meta of Romulus, or the Terebinthus Neronis, since taken down from its site on the Via Concilazione, and Paul at Tre Fontane on the Via Salaria. In Paul’s Martyrdom, see the matron Plautilla giving him the veil he used to cover his eyes, and perspectival landscape. In the predella below we have a Madonna and child flanked by two angels and Peter and Paul and the Apostles, who each carry their emblem (can you identify each?). | |

| In the next Room III we find Fra Giovanni da Fiesole, Fra Angelico, perhaps the saintliest painter ever, and the Stories of Saint Nicholas of Bari, a tempera on wood predella painted in 1437 for the Chapel of Nicholas in the Church of San Domenico in Perugia. The Fra’s paintings throughout Tuscany and beyond brought him to the attention of the humanist Pope Nicholas V Parentucelli (1447-1455), who called him to Rome to decorate his private chapel, near the rooms of the Stanze, with a Deposition and The Life of Saint Lawrence. Some say Nicholas’ predecessor Eugenius IV Condulmer (1431-1447) was the one who summoned him, but in any event Angelico’s work in the Chapel of Nicholas is now greatly admired, so much so that us commoners are not allowed to see it! Here at the Pinacoteca we can admire the scenes he painted from the life of Nicholas of Bari. Presumably he did not cry for this endeavor--he was known to weep whenever he painted a Crucifixion, and he never painted without praying first, and never repainted any painting, because he said his first effort was what God wanted. |  | Also in Room III is Fra Filippo Lippi’s Coronation of the Virgin, a tempera on wood triptych made in 1450 for the Monastery of Monteoliveto in Arezzo, originally in the Lateran Pinacoteca. His patron was the great Cosimo de Medici. The Fra was master of grace and proportion and design, and his draperies especially were far advanced over his contemporaries. He began the convention of painting greater than life-size figures dressed in contemporary clothing. He was able to give the faces of his subjects intense emotion. He died at the young age of fifty-seven, probably from poison administered by the family of one of the many women with whom he had an affair. In this Coronation we have Jesus and Mary in the central panel, with a fine set of steps illustrating the Fra’s ability with perspective. The donor Carlo Marsuppini, secretary of the Republic of Florence, is kneeling in the left panel, introduced by a saint monk. Gregory the Great is in the foreground left, with his trademark dove on his shoulder. An Angelic Choir plays in the background of both the right and left panels. Note the Fra’s exquisite draperies in Gregory, the two presenting monks, and the saint in the foreground on the right (who is he?). Also see here the use of shadows to create perspective, also an advance signaling that the Renaissance was about to bloom. |  | |

Masolino da Paniacale is also in Room II, with The Burial of the Virgin, a tempera on wood made in 1428 for the predella of the Colonna altarpiece once at Maria Maggiore. Masolino was an associate of the great Massaccio (1401-1428) (the great follower of Giotto in promoting naturalism) at the Brancacci Chapel in Florence.

We move on to Room IV, where Melozzo da Forli (1438-1494) holds forth. In 1475 Sixtus IV della Rovere (1471-1484) formally created the Vatican Library, at first composed mostly of what survived from the Muslim conquest of Constantinople. The Pope appointed the humanist Bartolomeo Sacchi, known as Platina, as the first Gubernator et Custos, or Director and Custodian of the codices. Melozzo was asked to fresco for the Library, the biblioteca latina, the scene of the Pope Appointing Platina, with the Pope’s nephews, including the future Julius II, in the entourage. The kneeling Platina points to the inscription which records the event. Guiliano della Rovere is the standing Cardinal, while his cousin Rafaello Riaro is the standing Cardinal to the right of the pope. Two other nephews, Giovanni della Rovere and Girolamo Riario are also here. Girolamo is the tall blue fellow. He was the mastermind of the Pazzi conspiracy executed on Easter Sunday 1478 in which Giuliano de’Medici, brother of Lorenzo the Magnificent (who, wounded, escaped) was assassinated at high mass in the Duomo. Rafaello Riario was a concelebrant for the Easter mass, an ignorant and thus innocent bystander who was eventually released by Lorenzo.

|  | The grand classical room in which the ceremony takes place has become, with its magnificent coffered ceiling, almost as famous as the della Rovere family actors in the painting. The fresco, made in 1477, was detached from its wall in the Apostolic Palace in the nineteenth century, and placed on a canvas when it was put up in the Pinacoteca. Melozzo’s colors are brilliant, his robes well formed, and the scene depicted well composed. The figures of the two notorious Roveres, one a pope and one to become a pope, and the almost as notorious Papal nephews, were forever imprinted on visitors to the city by this Melozzo fresco. |  | Also here, and for me more special, are the pieces of the fresco that Melozzo made for the apse at Santi Apostoli, the Ascension and the Angel Musicians. Here Melozzo displayed his absolute mastery of foreshortening, of perspective illusionism. Melozzo solved the problem of putting together a proper composition for a viewer standing directly underneath the painting, in this case, the apse of the Apostoli. Raphael was to develop this talent in the full after Melozzo! |  |  | |

Regrettably the fresco of the Ascension and the Angelic Choir was taken down in the eighteenth century (the main figure of Jesus made its way to the Quirinale Palace), but fortunately the pieces we see were saved. The heads of the Apostles are magnificent in their color and expression, but it is in the angels, each individually modeled with their instrument, that are so precious. I love the coloring and the beauty that Melozzo gave us in these heavenly beings.

Next for us comes Room VII, the fifteenth century Umbrian School. First here is Pietro Perugino (1445/50?-1523), teacher to Raphael, with his Madonna and Child with Saints, also called the Altarpiece of the Decemviri, which he has signed HOC PETRUS DE CHASTRO PLEBIS PINXIT. This is tempera on wood, made 1495 for the private chapel in the Palazzo dei Priori in Perugia. See the saints of Perugia at the Virgin’s feet: Lawrence, Louis, Herclanus and Constantius. This was such a special piece that Napoleon’s henchmen included it their list of 100 paintings stolen under the 1797 Treaty of Tolentino. Recovered fortunately by Canova in 1815. Perugino was known for his compositions, his depiction of space, and the economy with which he painted. Perugino was one of the four artists that Sixtus IV brought to Rome about 1480 to paint the lower register of his new Sistine Chapel. I will always associate him with Jesus Gives the Keys to Peter, which I am sure you have seen in books many times. Several of the frescoes he made for the Sistine altar wall were destroyed to make room for Michelangelo’s Last Judgment. Regrettable.

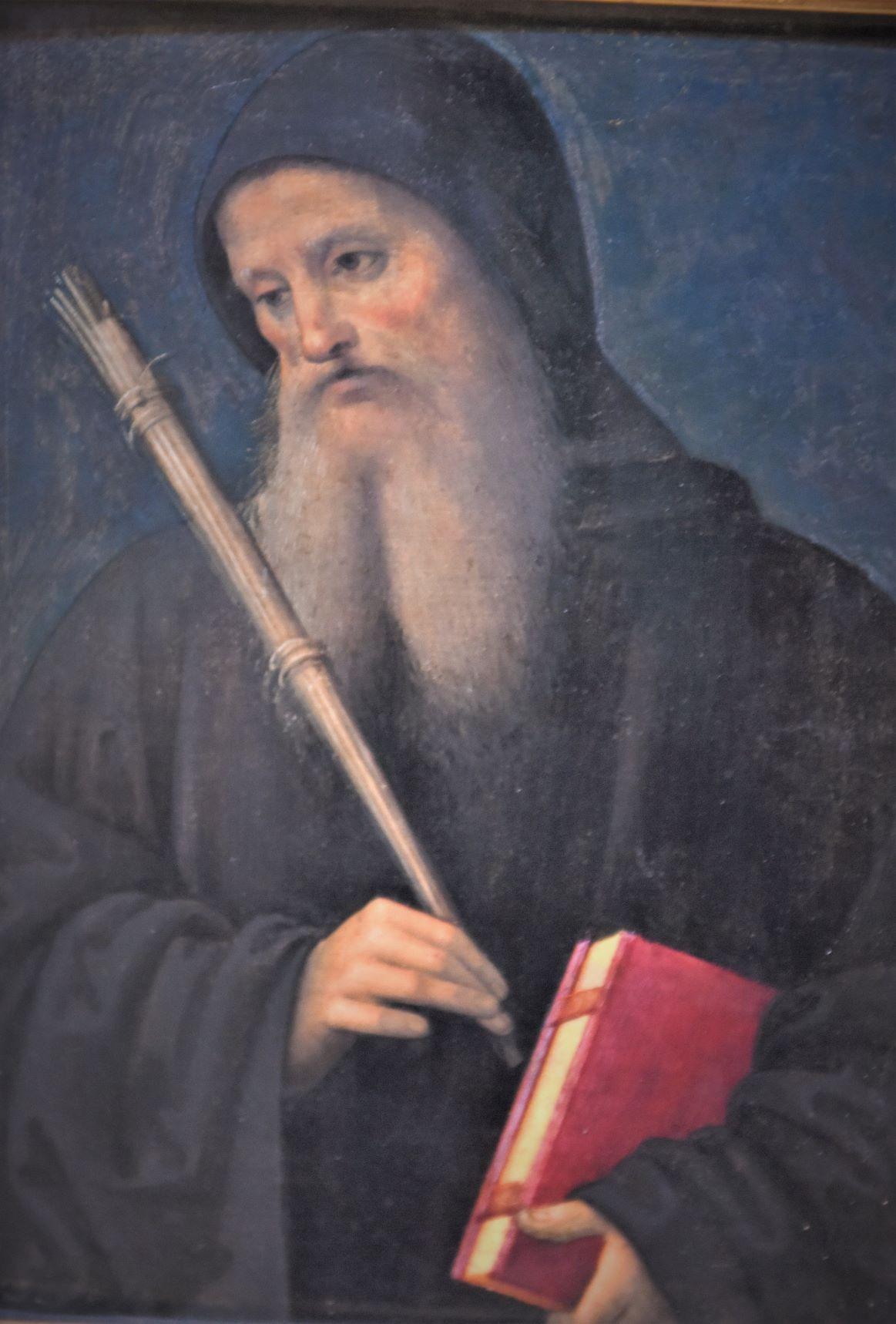

|  |  | Also here below the Decemviri is Perugino's Benedict | Also here is Perugino’s sometimes associate, Bernardino Pinturicchio (1454-1513), who in 1502 painted the Coronation of the Virgin, tempera on canvas, for the Umbertide Order Monastery, which is near Perugia. At the Virgin’s feet here we see Francis, Bernardino of Siena, Anthony of Padua, Louis of Toulouse, and Bonaventura. I have always loved Pinturicchio’s Ceiling at the Popolo and his Borgia Apartments at the Apostolic Palace. His colors are varied and stunning for me. He is often criticized for his use of assistants and his priority of speed over quality. Also here Pinturicchio’s Madonna dalla Davanzale. This is for me one of the most comforting and sublime Madonna’s in Rome |  | And now for the centerpiece of the Pinacoteca, Raphael in Room VIII. We have spoken much about Raphael of Urbino (1483-1520) elsewhere, and so we simply repeat here that he was, at least for me, the apex of painting. His was the culminating point for all the Renaissance artists who came before him, he represents absolute perfection. His figures are full to the brim with beauty and human emotion, properly formed from nature (unlike the muscular beasts of Michelangelo), his colors utterly enjoyable and so varied, his perspective and foreshortening absolutely perfect. His harmony, serenity, sense of balance and decorum are so evident in every single figure in every single painting. His palette was also unequaled, with ultramarine, lead-tin-yellow, carmine, vermillion, madder lake, brazilwood, metallic powdered gold and bismuth. |  |  | |

Here at the Pinacoteca we have three of Raphael’s greatest masterpieces. It is truly a miracle that they are here, since each of them was stolen by the French in 1797. We begin with the Oddi Altarpiece, the Coronation of the Virgin, painted 1502-1503. Napoleon stole this from the Oddi funerary chapel in Perugia. Symptomatic of his morality. The Louvre transferred it from wood to canvas. The altar piece is a narrative. Below the Apostles encounter an empty coffin filled with flowers, and then they turn their gaze above and see Mary who has risen into the heavens, surrounded by cherubs, with an angelic choir playing while Jesus crowns His Mother. Raphael painted the upper section first, and it is thought to be more stiff than the lower half, due to the stronger influence of Perugino, his teacher. The Apostles are more free form, with many different poses and foreshortening.

There are three sections of the predella of the Oddi altar that are also here at the Pinacoteca, which you see in the glass case by the guardrail in front of the three large paintings, giving us the Annunciation, the Adoration of the Magi, and the Presentation in the Temple. And also three pieces from the predella dell apala Baglioni, the La Speranza Carita, made in 1507.

|  |  |  |  | Next is The Madonna of Foligno, painted sometime before 1512 for Sigismondo de’Conti, who intended it for the main altar at Santa Maria in Aracoeli. The Conti house had been spared from a meteorite or lightning bolt, and Sigismondo offered this painting to Mary in thanksgiving. This painting too has an upper and lower part. Above is Mary with the baby Jesus, while below are the Baptist, Saint Francis, and opposite side the donor presented by Saint James (in Cardinal’s robes!). The little angel holds a panel for an inscription, which the donor intended to be filled with an explanation for his gift (never inserted as the donor died before the painting was completed). We can see in the background of the painting a bolt of lightning striking a town, presumably Foligno. Raphael’s techniques were still developing and improving at the time he painted this work, which can be seen with the increase over prior works in gestures and looks between the figures. This was perhaps Raphael’s most “atmospheric” painting, filled with clouds and lightning and rain, and even a rainbow. Note the cherubs forming the clouds. I love Mary’s beautiful blue robes, and the Baptist’s spiked hair! Mary also seems to be tickling the Christchild! In 1565 the donor’s nephew had the painting removed to the Monastery at Foligno, from whence Napoleon stole it in 1797. On its return it was kept safely at the Vatican. |  |  | |

Lastly we have the Transfiguration, Raphael’s last painting, completed in the year of his death 1520. This was commissioned by Giulio de’Medici, the future Clement VII. An oil on wood, intended by the Cardinal for the Cathedral of Narbonne, the Cardinal instead had it placed on the altar at San Pietro in Montorio, from whence, you guessed it, Napoleon stole it in 1797. When Canova secured its return in 1815 it too went to the Vatican. Another two part painting: above the Transfiguration. Moses and Elijah are stunning, suspended in mid-air, with soft colored robes flying in the air, a harbinger of Bernini, their feet pushing the air beneath them, as they magnify the Lord. The three Apostles are flattened by the dazzling sight. Jesus is in a majestic pose emanating grace and light, his robes too caught by the wind.

The two figures on the left of the Transfiguration are Saints Justus and Pastor, whose feast day is August 6. In the scene below a possessed boy is freed from the devil after the return of Jesus (the Apostles having failed without Him), the crowd pointing to Jesus and the boy. The scream on the boy’s face prefigures Caravaggio’s contortions! Raphael’s Transfiguration was his counter to the painting of Lazarus by Sebastiano del Piombo, also intended by the Cardinal for Narbonne. Del Piombo finished his work in 1518, and it was loaded with figures. Raphael, not to be outdone, added the lower painting to his Transfiguration, multiplying the number of figures. Matthew is the figure lower left, who motions us to wait for the miracle. The woman, in a “serpent’s contrapposto” with her hips and shoulders out of alignment, has not been identified. Philip, Andrew, Simon, and Judas Thaddeus are also here. Judas Iscariot may the figure on the far left, with the scowl.

|  | The Raphael Tapestries are not, I must confess, a favorite for me. For one they are dark, two I don’t like tapestries, and three I’m not able to appreciate the painter’s talent with the brush, and the perspective is lost on me. Leo X Medici (1513-1521) commissioned these for the Sistine. Raphael’s cartoons are now in the Albert Museum in London. Peter van Aelst of Brussels made the tapestries. The Tapestries give us the Life of Peter and Paul, and scenes from the Passion. | The tapestries in the Raphael Room include one copying Leonardo's Last Supper, above | Also here is Correggio’s Redeemer. Correggio, Antonio Allegri (1489-1534), was from the school in Parma, and a High Renaissance master of composition, illusionistic perspective, and dramatic foreshortening, and also a master of chiaroscuro. His most famous work is the fabulously foreshortened thousand figure fresco in the Doumo in Parma, the Assumption, which would be the inspiration for all the frescoed domes of Rome, including Sant’Andrea della Valle. Here we have a simple painting of Jesus. This was once part of a Tryptich, an oil on canvas 1523-1525 made for the Oratory in Correggio. |  | |

From the Raphael Room we now head back down the South Corridor toward the entrance/exit. First is Room IX, with Leonardo da Vinci’s (1452-1519) St. Jerome. Leonardo is known for giving us sfumato, the softening of the transition between colors, which he perfected by his study of optics and human vision, and his experimentation with the camera obscura. Leonardo’s Mona Lisa is perhaps the best example of what he called “without lines or borders, in the manner of smoke,” for we can see how the woman’s eyes blend with the areas around them through the shading. The Jerome was in the collection of one Angelica Kauffman, but upon her death in 1807 it was lost. It was found by Cardinal Joseph Fesch, but in two pieces. The part with Jerome’s lower body was found in the shop of an antique dealer, and it was being used as a coffer lid. The part with Jerome’s head was found in a shoemaker’s shop where it was the seat of a footstool.

The painting is certainly not “pretty,” and this is because Leonardo left it in draft form, perhaps because the subject was penitent. Jerome is in a rocky desert, having deserted the pagan literature in favor of a life in the desert studying Hebrew and biblical texts. It was this study that led Jerome to create the Vulgate translating the bible from Greek into Latin. Leonardo loved the study of human anatomy and also landscapes. Here he gives us both, with a Jerome we won’t forget (we will see another emaciated Jerome further down the corridor), with his hollowed out cheeks and his gaze to God above for mercy, entirely fitting with the rocky crags around him. Also note Jerome’s ever present companion the Lion (sometimes a skull takes his place or accompanies him), who doesn’t seem too happy with the Saint.

|  | Also in Room IX is Giovanni Bellini’s (1430-1516) Embalming of the Body of Christ, dating to 1471/4, made for the Church of San Francesco in Pesaro. Bellini, a Venetian whose separation from the other Venetians here is not explained, was known for the lack of emotion in his figures, and this painting is certainly no exception, especially in Nicodemus who holds the embalming oil with such passivity. Napoleon stole this one too. | There is close by here a painting by Domenico Ghirlandio (1448-1494), but I suspect it is his school because it just does not seem up to the rest of his work. It is a Nativity, given with a gold background instead of a scene. Ghirlandio was one of the painters brought by Sixtus IV for the lower register at the Sistine, and he did the best work there of all the artists employed. He had the middle Renaissance gifts, but the art as you can see in this Nativity was still emerging. |  | |

Which brings us to the Venetian portion of the Renaissance painters, and Room X, where have Tiziano Vecellio, known as Titian (1490-1575), and Paolo Veronese (1528-1588). Titian’s Modonna dei Frari, an oil on canvas painted 1528 for the Church of San Nicolo dei Frari (or della Lattuga, “of the lettuce”!—not sure how it got that moniker) in the Lido in Venice, has Saints Sebastian, Francis, Anthony of Padua, Peter, Nicholas, and Catherine of Alexandria. It is signed TITIANUS FACIEBAT. Note that Catherine bears the palm of martyrdom while the other martyrs do not for some reason. I especially like Peter here, for his bald head and wonderful white beard, and the impressive folds Titian has given his cloak. And of course we admire the colors, for Venice was champion of colors.

Titian’s Doge Niccolo Marcello may be the most famous side view portrait ever—how can you forget this man with that nose and Venetian cap and tasseled cape? Made in 1541 in oil, the bronze/gold coloring contrasting with the flesh tones of the Doge’s face are testimony to Titian’s command of color.

|  | Paolo Veronese’s Helen with the True Cross, an oil on canvas made c1580, has Constantine’s mother Helen in Jerusalem, in the middle of a dream guiding her to the true Cross, which we see held by a little angel. The colors of her dress are completely Venetian, and the folds are well and carefully done. Also here is Veronese’s Nativity with Saints. The saints are the Baptist, Saint Dorothea, and Saint Andrew. A beautiful array of color. | In Room XI we have Giorgio Vasari’s (1511-1574) Stoning of Saint Stephen, Ciuseppe Cesari’s, known as the Cavaliere d’Arpino (1568-2640), Annunciation (I like the color and the folds in the angel’s cloaks), and Federico Barocci’s (1535-1612) Rest on the Flight into Egypt. |  | Next on our chronological trip is Room XII, which has a mixture of what some would call Proto-Baroque and Baroque and counter-Baroque works. First here is the popular painting of the Entombment of Jesus by Michelangelo Merisi, known as Caravaggio (1573-1610). This was an altarpiece (his best) made in 1604 for the Oratorians at the Chiesa Nuova, Santa Maria in Valicella. It was commissioned by Girolamo Vittrice, an Oratorian, for the funeral chapel of his uncle Pietro, a close friend of Filippo Neri. In the painting Nicodemus holds the body of Jesus, with his arms under Jesus’ knees. Saint John has one arm under the arm of Our Lord, whose face is upturned and with the pale of death. Behind Nicodemus are the mourning Marys, one with her arms upraised, another veiled, a third directly gazing on Jesus. All of Caravaggio’s strengths are here—the real life drama which makes us feel we were there at this terrible moment, the perfect representation of the figures, the brilliant use of chiaroscuro. Caravaggio here copies the limp arm of Jesus from Michelangelo’s Pieta, and we see the same prominent veins. Likewise in the arm of Jesus, where the flesh bulges, here over the hand of John, in the Pieta over the hand of Mary. The realism is unparalleled in other art: “Nicodemus stoops awkwardly as he clasps the body around the knees in a bear-hug.” Andrew Graham-Dixon. Just look at the feet of Nicodemus, veined and creased where they meet his ankle. Jesus’ feet “dangle” just like they would have in real life. Mary, on the left, has a wimple, so that she looks so beautifully like a nun, while the Magdalene reaches up to the Father. An incredibly theatrical performance that does indeed presage the coming theatre of the Baroque, but so unlike the Baroque in its realism. Like so many other treasures of the Vatican, it too was taken by the French, in this case from the Chiesa Nuova, and returned after Waterloo and the Treaties of Paris and Vienna. |  | Annibale Caracci was the founder with his brother of the Bolognese school, founded on a renewed Classicism. Domenico Zampieri (known as Domenichino for his small stature)(1581-1641) was of this Bolognese school, and his Last Communion of Saint Jerome is in Room XII. For two and a half centuries this Last Communion was considered one of the great pictures of the world. It was the “ideal altarpiece of its decade” (Ellis Waterhouse), painted for San Girolamo della Carita. Jerome would say mass daily at Bethlehem’s church, and in the painting he receives the Eucharist for the last time. He is carried into the church, where he kneels on the predella of the altar, collapsing backwards into his red mantle. His skin hangs from his limbs as a young man supports him. The priest, deacon, and subdeacon are all in awe of the sacred moment, and every eye in the painting is fixated on the saint. Yes, this painting too was rescued from the French after Napoleon’s defeat. |  | Guido Reni (1575-1642) was also from the Caracci school. He abandoned Mannerism for the new classicism of the Caracci. Room XII is home to his first major work in Rome, the 1604-1605 Crucifixion of Peter, an oil on canvas that had been made for the Abbey at Tre Fontane. Reni was of course well aware of the dramatic art of Caravaggio, and this Crucifixion was his attempt to marry the “decorous models and studied composition, and suggestion of landscape setting” to the “bold lighting” of Caravaggio. Waterhouse. Caravaggio fell shortly after this, and Reni thereafter went full Classical, and stayed there. The Crucifixion of Peter is extraordinary work to be sure, but it is hard not to think back to Caravaggio’s depiction of Peter’s death at the Cerasi Chapel at Santa Maria del Popolo. Also here is Reni’s Matthew Inspired by an Angel, with a very expressive Matthew who looks more than intently at the angel, who dictates to him (just look at her making a point with the comput digitalis of the ancients). |  |  | Andrea Sacchi (1599-1661) was also a great champion of the Classical. He made the Miracle of Saint Gregory for Pope Urban VIII Barberini (1623-1644) for the Chapter House of the Canonica of Saint Peter’s 1625-1627. This was admired as one of the great masterpieces of devotional altarpieces of the age. Here Gregory pierces a corporale and the blood of Our Saviour pours forth before an incredulous prelate. Gregory’s vestments are probably far beyond anything the Great Saint would have worn, but they are beautiful nonetheless. The man on the left is the most stunned by the event! |  | Giovanni Francesco Barbieri (1591-1666), known as Guercino because of his squint, was from Cento, near Ferrara. He had no teacher and taught himself simply by admiring paintings of others. He had the Venetian talent for texture with paint, and “strong contrasts of light and shade, in which the forms are partly dissolved in shadow,” called luminismo. Waterhouse. He also had a “lyrical tenderness and delicacy of feeling.” His style evolved into full baroque, with movement and emotion and theatre and loads of figures. This room has his Mary Magdalene, with the instruments of the Passion, painted in 1623 for her church in Rome, now taken down, and housed in the Quirinale for a long time, and also The Baptist (contrast this completely human Baptist who asks God for guidance with Caravaggio’s awfully feminine Baptists), and Santa Margherita of Colonna ( beautiful and saintly woman indeed). |  |  |  | We finish in Room XIII with Nicolas Poussin (1594-1665), who worked in Domenichino’s studio, and who was a stalwart Classicist reactionary to the invading Baroque of Guercino and others, an ally of Andrea Sacchi (1591-1661), foremost of the classicist holdouts. A Frenchman, he came to Rome, his idol the recently deceased Raphael. He detested the art of Caravaggio, whom he regarded as an enemy of the Roman classical tradition. He joined an academy of artists opposed to the growing baroque, whose theatrical aspects he also regarded as anti-classical. In 1630 he painted the Martyrdom of Saint Erasmus we see at the Pinacoteca. He was engaged by the Fabbrica of Saint Peter’s (those in charge of the decoration and maintenance of the church) for one of the three lesser altarpieces in the left tribune of the Basilica. The scene he painted is grisly, with the executioner cutting out the saint’s entrails. Note the pagan priest on the right entreating the still alive Erasmus to adore the statue of Hercules upper right. Poussin’s naturalism and devotion to the proper is evident. Poussin signed the work “NICOLAUS PUSIN FECIT.” Those of us who live in Minneapolis know Poussin from the Institute of Arts which has one of his early works, the Death of Germanicus, painted 1627 for Cardinal Francesco Barberini. |  | In Room XIII we also have the master of Baroque painting, Pietro Berrettini da Cortona (1596-1669). His most famous painting is perhaps the Rape of the Sabines, now at the Capitoline, but his best work is the ceiling at the Salone in the Palazzo Barberini. This was the “most breathtaking achievement in Roman Baroque painting.” Waterhouse. Here we have the Vision of Saint Francis, a scene in which Mary delivers the baby Jesus to Francis, in rapture. |  | |

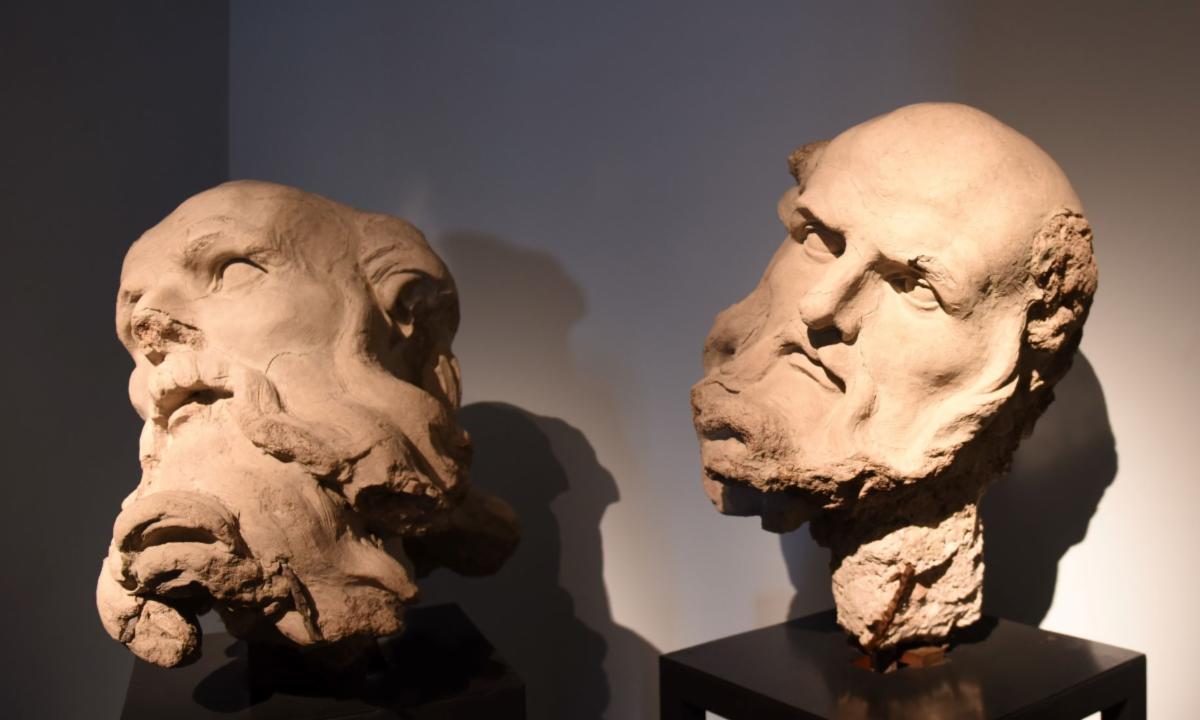

We finish with Room XVII, home to Gianlorenzo Bernini’s terracotta (terracruda) modelli grandi that he made in preparation for the Cathedra Petri, which include the angels and the heads of the Church Fathers (Chrysostum and Athanasius). Bernini made these both to determine if they were the appropriate size for the site and for the bronze-casting process. The material he used was a combination of clay and straw which was fixed onto a framework of iron and cane. Bernini loved to model, or use the additive process to create a figure, versus the reductive process he would usually use to carve out his figures in marble. The additive process was so much easier for him, and allowed him to be far more creative, since he could go back in his work, modify it at will.

Bernini brought Andrea Sacchi to Saint Peter’s to view his modelli after he had made them and put them up. Sacchi stopped just a little past the Crossing, and told Bernini “(I)f you wish to know my opinion, this is the place from where (the work) must be seen.” And from that point, Sacchi said, it was clear that Bernini’s first set of modelli angels were too short. Bernini took Sacchi’s advice and increased the height of the angels some nine inches. We get to see both the original smaller set and the final larger set of Bernini’s angels in Room XVII.

We also get to see the marvelous heads of John Chrysostum and Athanasius, two of the Fathers who stand astride the Cathedra Petri. Like the angels, these modelli were not made by Bernini’s assistants, as was usually the case for modelli, but by the master himself. These modelli are some of the best that Bernini made, and he made many of them.

The kneeling angels here were the ones Bernini used for the Chapel of the Holy Sacrament. For myself, I actually enjoy Bernini’s small bozzetti and the larger modelli more than the final bronze or marble because I can see Bernini’s individual strokes of his tools, and his hands. The roughness is more beautiful than the final polished product.

You will see some of Bernini’s small bozzetti terracottas if you visit the Christian Museum, though they are enclosed in glass. One was for the Habbakuk and the Angel, the other for David in the the Lions’ Den, both for the Popolo. The small bozzetti were solely to help Bernini make his sculpture, not to determine the final size as were the modelli here.

|  |  | |

Now we exit the door we came in, or we go to the left to visit the Gregorian Profane Museum. More on that on our next segment of our visit to the Vatican!! Shortly we will enter the Apostolic Palace and the masterpieces of Fra Angelico, Pinturicchio, Raphael, and Michelangelo!

Copyright Greg Pulles 2023 all rights reserved.

| | | | |