|

Raphael: The Angel Unchains Peter. Room of the Eliodoro |

|

THE STANZE OF RAPHAEL SANZIO | |

|

Today we visit perhaps the most brilliant work of art ever created—the Stanze of Raphael in the Apostolic Palace. Pope Julius II della Rovere (1503-1513) made his home in the first floor of the Apostolic Palace, the Apartments made by his predecessor the Borgia Pope Alexander VI (1492-1503), whom he detested. In 1507 he decided to move to the floor above, where there were three small rooms and a larger audience room. He brought in notable artists to fresco the rooms, including the then most famous frescoist in Italy, Pietro Perugino (1448-1523). In 1508 he summoned the 24 year old Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino (1483-1520) to decorate one of the rooms, then Julius’ library, and Julius was so impressed that he put Raphael in charge of the entire project. The rooms were forever after called the Stanze of Raphael.

Raphael abandoned most of the work from other artists already in place, saving just one ceiling that had been frescoed by Perugino, with whom he had worked at Perugia, perhaps as his student. After Julius’ death in 1513, his successor Leo X Medici (1513-1521) had Raphael continue. After Raphael’s death in 1520 his assistants completed the last room, the large audience hall that came to be known as the Hall of Constantine, finishing in 1528 under Clement VII Medici (1523-1534).

These rooms are simply a pure delight. Raphael gives us the full splendor and joy that he put into his paintings, with vibrant color, wonderful but not overdone modeling of his figures, and great talent in scene setting. He continued the tradition of Ghirlandaio and painted famous contemporaries into the scenes, and so we have great fun in trying to name the subjects—not only the historical subject but also the contemporaries he painted into the pictures. Thus Plato becomes Leonardo, Euclid becomes Bramante, Hiracletus becomes Michelangelo. And every historical Pope had a contemporary—and so Gregory the Great has the likeness of Julius II, and Leo IV that of Leo X. And he even manages to sneak in notorious figures such as Savanorola, who had been martyred at the stake in Florence Square just ten years previous, and his own self portrait and that of his associate Il Sadoma.

Raphael began with the room that has come to be known as the Signatura, which Julius decided he wanted to use to sign important papal documents, especially amnesties. The theme was the Good, the True, and the Beautiful. One wall would have the School of Athens, another the Mount of Parnassus, another the Disputation of the Blessed Sacrament, and finally the Virtues. Each painting was paired with the tondo above in the vault—the personification of Philosophy is above the School of Athens, a winged Poetry is above the Parnassus, Theology is above the Disputa, and Justice is above the virtues Fortitude, Prudence and Temperance.

| |

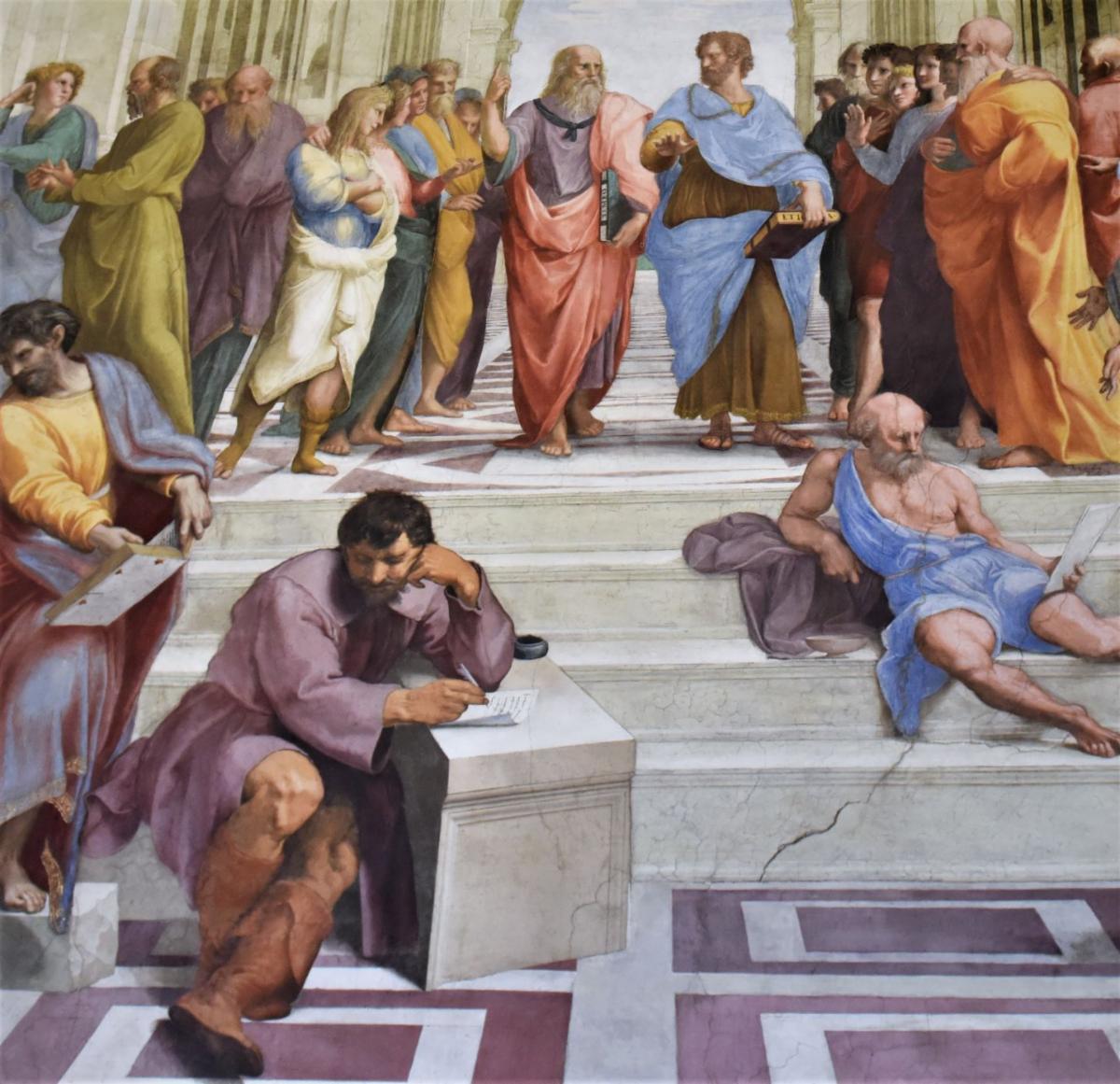

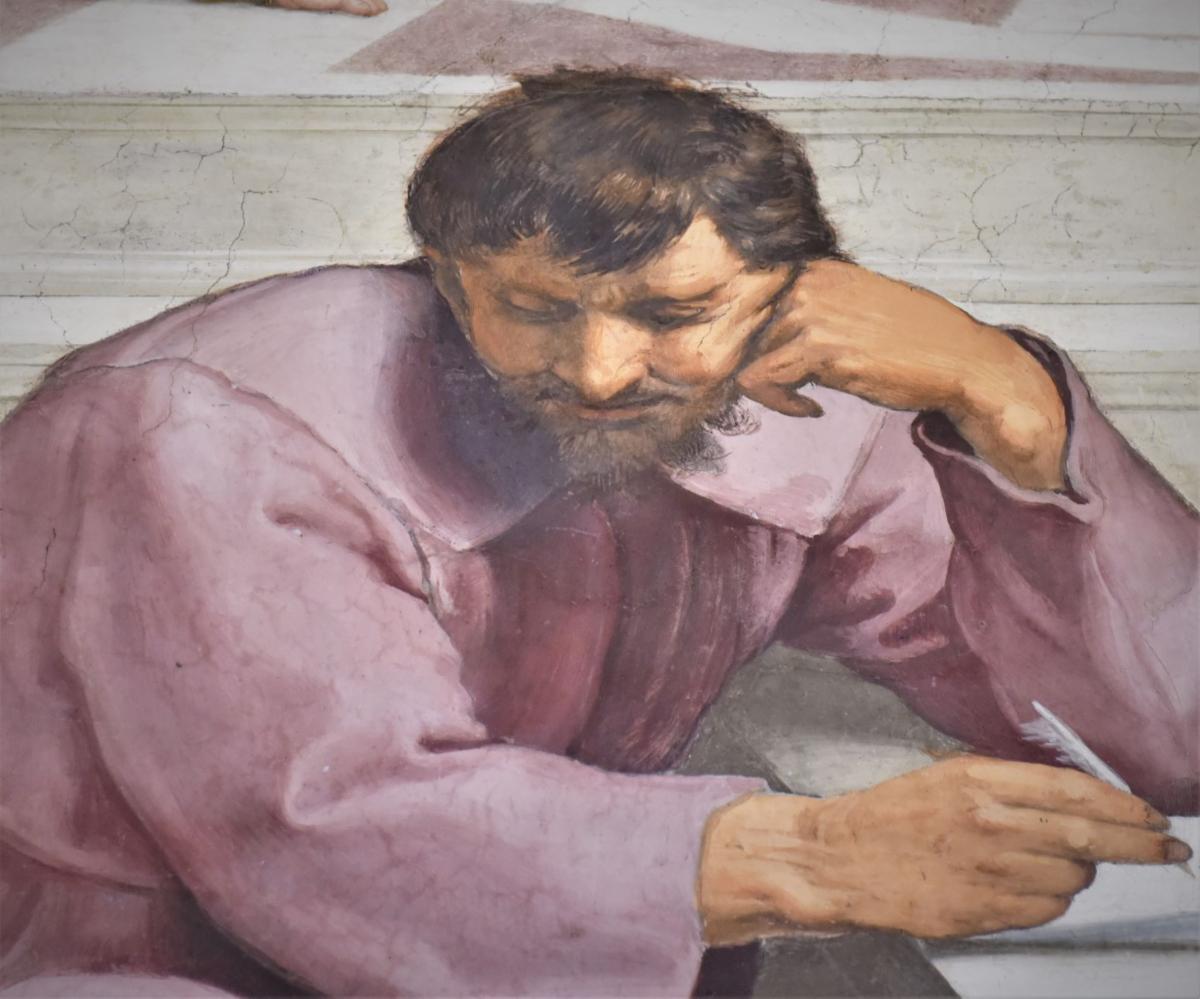

The School of Athens is entirely by Raphael, who was to use assistants as his work in the Stanze progressed. The scene is the Basilica of Maxentius on the Forum, and Raphael gives us all the famous Greeks and more. No one knows for sure who all the subjects are! There are the easy ones—Plato and Aristotle in the center. Plato holds his Timaeus, pointing to the heavens (the sphere of higher thoughts), while Aristotle with his Ethics points towards the earth (the sphere of natural phenomena). Plato may be Leonardo da Vinci, with his long white beard. Diogenes is sprawled out on the steps, his discarded cup next to him on the steps. Socrates is probably the man on the left in the green, making his point with a comput digitalis, Chrysippus, Exenophon, Aeschines and Albiades in the group to which he lectures. Epicurus is the man in the lower left of the scene, crowned with vine leaves, and he is certainly writing about his hedonism. Pythagorus is teaching his diatessaron from a book, the turbaned Averroes is watching from behind. Heraclitus--Michelangelo--is thinking on the steps. On the right, Raphael painted his friend Bramante as Euclid, who is seen bending over his slate with a compass. Note here that Raphael has signed the work on the tunic: RUSM: Raphael Urbinas Sua Manu—"by the hand of Raphael of Urbino”. On the right of Euclid is the geographer Ptolemy holding the globe of the earth. The astronomer Zoroaster holds the globe of the sky. Raphael is the young man on the side of these two, painted next to his fellow painter Il Sodoma, Giovanni Bazzi (1477-1549). |  | Plato (da Vinci) and Aristotle, Socrates in green on the left, below Heraclitus writing (Michelangelo) and Diogenes on the steps. | Pythagorus with Averroes looking over his shoulder | Euclid (Bramante)--Raphael placed his signature on his collar |  | |

Bramante had arranged for Raphael a prominent seat at the mass Julius held in the Sistine on the feast of the Assumption of 1510, the first opportunity for the pope and a chosen few to see Michelangelo’s ceiling, which was one-half finished. Raphael was amazed at the work, especially Michelangelo’s ability to create sculpted figures in fresco, robust athletic figures in brilliant colors. He altered his style, which thereafter became decidedly more muscular. The delicate gave way to the rugged. Here in the Signatura, he added, a full year after he finished the School of Athens, the figure of Heraclitus. He first drew the figure in red chalk on the fresco, then transferred that onto a piece of paper, then made a cartoon, chipped away the original intonaco, laid new plaster and then with a single giornata of new plaster painted what came to be called the “thinker.” Raphael made him muscular, called him Heraclitus of Ephesus, and gave him the likeness of Michelangelo with his broad and flattened nose (and Heraclitus was known for his terribilita just like Michelangelo)! Unlike the other 55 barefooted and fully robed figures in the School, Heraclitus has leather boots and a cinched shirt.

The next wall, the Dispute on the Blessed Sacrament was also entirely from Raphael’s hand. God the Father is personified in the upper section, surrounded by six angels and a host of golden cherubs, and blessing all those below in the Church Triumphant and the Church Militant. Below the Father is the cloud born Glorified Son, with the wounds of the Passion, and His Mother and the Baptist astride him. Then we have the Church Triumphant, with twelve saints, left to right: Peter, Adam, John the Evangelist, David, Lawrence, Jeremiah?, Judas Maccabeus?, Stephen, Moses, James the Lesser, Abraham, and Paul. Peter holds his keys, Adam crosses his legs, a crowned David plays his harp, Lawrence points something out below to Jeremiah. Stephen on the right holds the palm of martyrdom, while Moses sports an impressive set of rays coming out of his head. Abraham looks below, while Paul holds his sword and Epistles. The four little angels hold the gospels, the Holy Spirit in the form of a Dove in the middle, while hundreds more cherubs support the clouds that support the saints. Down below on the earth we have the Church Militant, giving us the Disputa, with the Blessed Sacrament on the altar. Can you guess which Pope is represented in the popes here? It’s Gregory the Great on the left. We see Gregory’s name in his halo. On the far left we have Fra Angelico, then Bramante at the table with the book. Saint Jerome, also with his name on his halo, is to the right of Gregory. On the right we have Saint Ambrose, also name on his halo. He is talking to Pope Innocent III. To the right of Innocent is Saint Bonaventure, name in halo, then Sixtus IV della Rovere, then in profile the laureled Dante, and then peaking out from the other figures, in his black hood, the Dominican firebrand reformer Girolamo Savonarola da Ferrara. Perhaps Julius had Raphael insert him because Borgia had put him to death, but it is odd as the Franciscans (Julius was a Franciscan) in Florence assisted in his death. He has not been honored as a saint by the Church, but he should be. Fearless in his pursuit of faith and in his rejection of the worldliness of his times.

|  | |

The Church Triumphant--Peter, Adam, John the Evangelist, David, Lawrence, and Jeremiah(?) | |

The Church Triumphant--Judas Maccabeus(?), Stephen, Moses, James the Lesser, Abraham, and Paul | |

The Church Militant--Gregory the Great (Julius II) and Jerome | |

The Church Militant--Ambrose and Augustine (mitred) Thomas Aquinas, Innocent III, Bonaventure (haloed with his name), Sixtus IV della Rovere (Julius' uncle), Dante (laureled) and last but not least in the way back the Dominican reformer Savonarola (Bonfire of the Vanities) | |

I acquired this small print made some hundred years ago--Raphael's painting of Julius II. The shopkeeper of the Antique Store had labeled it "Old Italian Gentleman." It doesn't photograph well! This was painted after the pope stopped shaving his beard--he vowed not to shave until he had driven the French out of Italy. Compare this likeness to the five likenesses of the pope Raphael painted into his Stanze. | |

The third wall Raphael frescoed in the Signatura is the Mount of Parnassus featuring 28—count them-- ancient and contemporary Poets. Apollo is at the center playing the lyre (the lira da braccio), with the nine muses surrounding him. Calliope, the muse of epic Poetry, is at his feet to his right with horn, while Terpsichore, the muse of lyric Poetry, holding the zitheris is at his feet at his left. All the other Poets are here. The blind Homer (here Raphael used the priest Laocoon as his model) surveys the scene. Behind is Dante in profile. Virgil is here too, perhaps modeled after one of Laocoon’s sons. The great female poet from Lesbos, Sappho, reclines in the foreground, wearing blue and white with gold. The courtesan Imperia is said to have posed for this picture, she reputed to have been the most beautiful woman in the city. She turns toward Alcaeus, Corinna and Petrarch, who peeks from behind a tree, and Anacreon. In the foreground we see Ovid with a finger to his lips, and he speaks with Sannazaro and Horace. The seated poet on the right next to the window, a late addition, may be pointing out to us the view out the window, which at that time would have given us the full uninterrupted length of the majestic Cortile of Bramante. The man with the white beard on the right above could be Tebaldeo, who faces Boccaccio, Tibullus, and Arisoto. This was the golden age of poetry indeed. | |

| |

Pay special attention to all the ancient masks and musical instruments, Raphael took them from the ancient sarcophagus we can now visit in the Palazzo Massimo, which has five muses holding these very masks and musical instruments. Below the monochrome scenes give us Numa Recovering the Sybilline Books, and Augustus Saving the Aeneid. The Lutherans did great damage to the bases here in the Sack of 1527, some say the rooms were used as stables. Luther’s name was carved into the School of Athens. All repaired now, but different.

The last wall that Raphael painted in the Signatura was called Justice, and it depicts the Cardinal and Theological Virtues, representing the subjective Good, with the highest of the Cardinal virtues, Justice, above. Fortitude holds the oak branch from the Coat of Arms of the pope’s Rovere family. Prudence has two faces, and looks into a mirror. Temperance of course holds the reins. Justice is in the tondo above. The cherubs are intended to represent the theological virtues. Faith points toward God above, Hope holds a torch, and Charity shakes the acorns off the Tree of Fortitude. Here on the right side next to the window we have Saint Raymond of Penafort presenting the Decretals to Gregory IX (1227-1241). Julius II is Gregory IX here! Raymond (1175-1275) was a Catalan Dominican who compiled the Canonical Laws the Church was to follow until a modern code was adopted in 1917. On the left side The Emperor Justinian (527-565) receives from Trebonian the Corpus Juris Civilis, the Code of Justinian, which was the law of the eastern Empire 534-1453.

|  | |

The Tondo above the Wall of Justice actually carries Justice, she the most Important of the Cardinal Virtues | |

Gregory IX (Julius II) Receives the Decretals from Raymond | |

Before we move on, be sure to admire both the tondos in the vault, probably by Raphael and not assistants, and the rectangular fields-quadri-which have the Judgment of Solomon (to accompany the tondo Justice)(the angel who stops the servant about to cut the baby in half is very special—her face is one of the most beautiful you will see in Italy—her arm suffers from the muscular that Raphael allowed to creep into his works after he saw the ceiling in the Sistine), the personification of the Cosmos (see the system of the cosmos-- the CAUSARIUM COGNITO), to accompany the tondo Philosophy, the Punishment of Marsyas (he is flayed for challenging Apollo—Marsyas’ pointy ears are special, and his executioner has a wicked look indeed), to accompany (not sure why) the tondo Poetry NUMINE AFFLATUR), and the Fall of Adam and Eve, to accompany the tondo Theology (DIVINARE NOTITIA). Note that in all of the quadri, in contrast to the tondos, Raphael has developed his “skill” in creating figures with more muscular forms. Not nearly as overdone as Michelangelo’s subjects at the Sistine. | |

Raphael completed the central hall of the Signatura in the summer of 1511. Raphael had labored on it for 30 months. The pope then had Raphael move on to the next room, which came to be called the Stanza di Eliodoro for the painting of the Expulsion of Heliodoros from the Temple. Raphael was anxious to demonstrate in this room what he had learned from Michelangelo, and the pope on the other hand just wanted his rooms finished. The pope had survived a near death illness in 1510, in the months after the Mass of the Assumption held to unveil Michelangelo’s ceiling. He pushed his artists to move forward. | |

The Expulsion of Heliodorus. Raphael's first work after he saw Michelangelo's Creation in the Sistine. The angel in the foreground best shows how Raphael adapted to the style Michelangelo introduced., and he is thought to be taken from God the Creator--note his extended finger. Above in the vault a fresco probably not from Raphael of the Miracle of Moses and the Burning Bush | |

This room should probably be called the Room of the Miracles, since each wall gives us a miracle, each from a different historical period. In the Expulsion, Raphael gave his figures the athleticism he saw in Michelangelo’s work. To this he applied his usual mastery of space, with a carefully worked out architectural programme. The Temple in Jerusalem becomes a Roman basilica. At the beckoning of King Seleucus and in the time of the Maccabees Heliodorus attempted a robbery of the treasury. God sends a heavenly messenger on horseback with two assistants, and they take Heliodorus to the ground and trample him. The High Priest Onias is above, praying for this miracle. The two avenging assistants float through the air, the best example of Raphael’s new style. The one in the foreground is thought to be modeled after the figure of God the Creator in Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam, which was finished in November of 1511, and thus probably seen by Raphael before he finished his Heliodorus in the early months of 1512.

Julius was passionate about expelling the French from Italy, and the Heliodorus was likely Raphael’s attempt at allegory, with the sprawling Heliodorus and his loot a representation of the French expulsion from Italy. Onias here wears the tiara and blue and gold robes. Julius is in the scene, brought in on a litter, the sedia gestatoria, masterfully painted with his characteristic look, il papa terriblile. The two litter bearers may be the engraver Mercantonio Raimondi and Raphael’s student Giulio Romano. The Lutheran German Landsnecht defaced the figure of the pope here in the Sack of 1527.

One of the pope’s favorite people was Federico Gonzaga, the young boy who served for three years as the pope’s hostage. The pope credited the boy (who never left the pope’s side no matter how sick he was) with saving his life in the summer of 1510 when he hovered near death for two months. One of the boys in the Expulsion is Federico, which one is not clear. We also think the woman extending her right arm on the left side of the painting is Raphael’s mistress, the baker’s daughter, La Fornarina, Magarita Luti.

| |

Do you see God the Creator from Michelangelo's the Creation at the Sistine? | |

From Heliodorus, Raphael moved on in the early months of 1512 to the next miracle, the Mass at Bolsena. In 1263 a traveling priest stopped to say mass at the Church of Santa Cristina in Bolsena, a town some 60 miles north of Rome. The priest had suffered doubts about the Catholic doctrine of Transubstantiation—the transformation of bread and wine into the Body and Blood of Christ that occurs at mass as the priest conducts and repeats the sacred mysteries that Jesus gave us at the Last Supper. Here during this mass a Cross of blood appeared on the Sacred Host during the Consecration. The priest would wipe the stain with the corporal, but each time a new Cross would appear on the Host. This miraculous corporal was then preserved above the high altar in Orvieto Duomo. Julius had said mass at the Duomo and exposed the corporal prior to his successful march on Perugia and Bologna in 1506. Thus it was no surprise that the Pope wanted Raphael to paint this miracle in the Stanze, particularly because Julius was then under attack by the French, who under Gaston de Foix would defeat the pope’s armies at Ravenna on Easter Sunday in April of 1512. Julius of course is painted into the scene, bareheaded and still bearded (he had promised not to shave until he had driven the French from Italy). This was the fourth time Raphael had painted Julius into the Stanze. Note the four Swiss Guards in the lower right. Julius had created the Guards as the official papal escort in 1510, and given them their distinctive costume of berets, ceremonial swords and striped uniforms, designed by Michelangelo. Here we see the Venetian influence of color, and many see the colors of Venice in the dark hues of the velvet worn by the Guards. The Swiss were not in Raphael’s original drawing for the Bolsena, and we think Julius had them added after their successful traverse of the Alps in May 1512 , which enabled them to secure Verona for the Pope. The Pope was overjoyed—the defeat at Ravenna had been overcome. | |

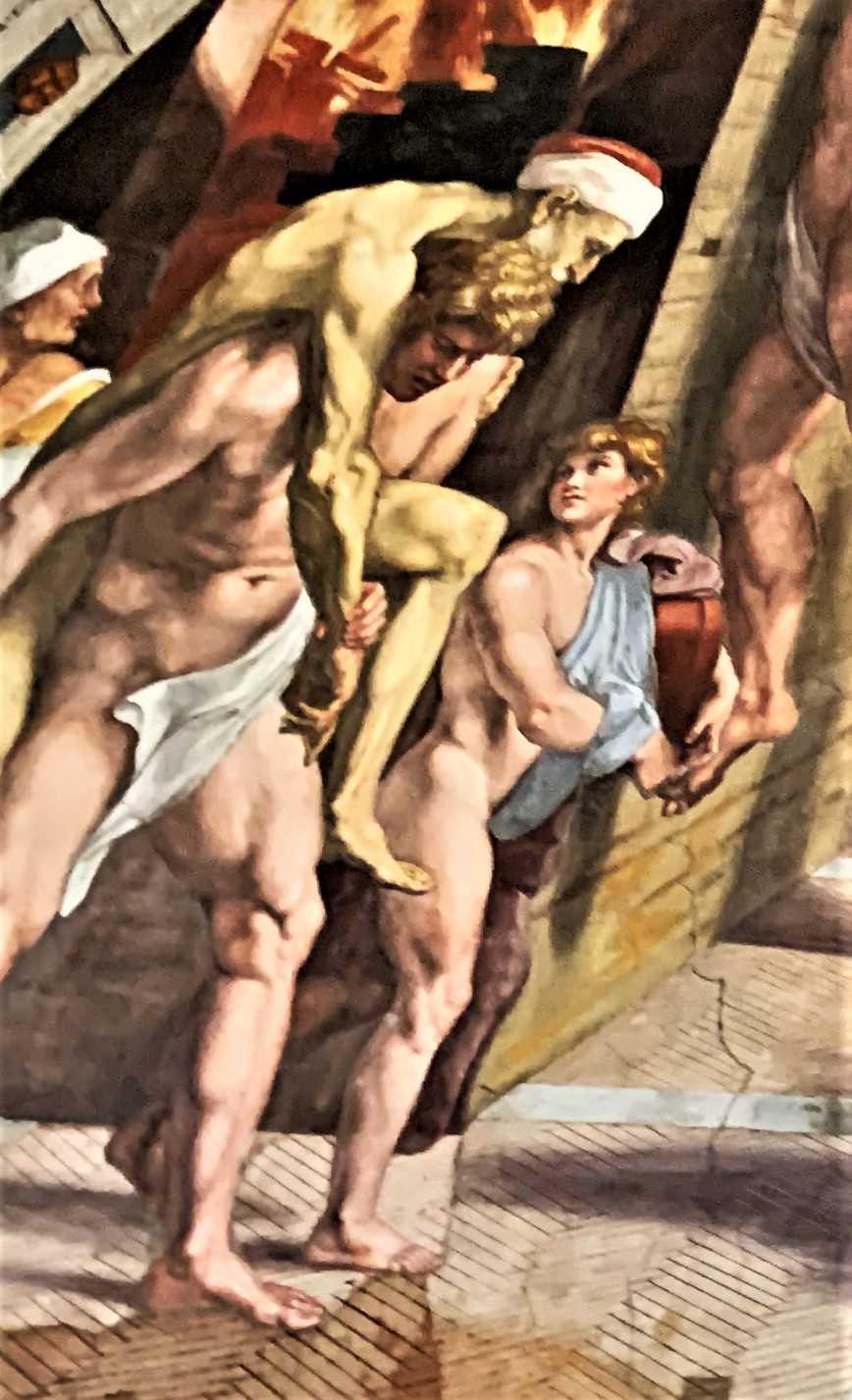

Raphael moved on to the third wall in the Eliodoro, the miracle of the Repulse of Attila. Julius died in February of 1513. Raphael finished the Attila in 1514. In 452 Attila the Hum was advancing south in Italy to take Rome. Pope St. Leo the Great advanced from Rome to stop him. The pope met Attila on the Adige River, somewhere near Mantua. Here the miracle: Peter and Paul appeared to Attila and threatened him, and the Hun then took up the pope’s warning and left Italy. Raphael originally painted the face of Julius on Pope Leo, but after the ascendancy of Leo X Medici (1513-1521) Leo X’s face was substituted. The problem was that Cardinal Giovanni de’Medici, to become Leo X, was already in the painting, behind the pope. Thus we see him twice in the fresco! Note the Colosseo in the painting, here transported to Mantua! | Atilla recoils from the vision of Peter and Paul in the heavens above him | Leo commissioned Raphael to do the last wall in the Eliodoro, the Liberation of St.Peter. The Acts of the Apostles tells us that Peter was freed from his chains in the Jail of Jerusalem by an angel, who woke him in the night and led him into the city while his guards slept. Raphael gives us this miracle in a whirlwind of light, the light from the angel, the light from the moon, the light of the morning, and the light from the torch of the soldier. These lighting effects make this, in my view, Raphael’s masterpiece in the Stanze. This supreme mastery of light was to be inspirational for both Caravaggio and Bernini. The incorporation of the real window into the scene places us directly into Peter’s escape. |  |  | In 1514 Leo X had Raphael move directly onto the next room, the Stanza dell'Incendio, which Raphael finished 1517. One of the subjects here was the fire that broke out in the Borgo neighborhood in 847, which gives the room its name. All of the walls in this room involve a Leo pope, and so it could more appropriately be called the Room of the Leos. Raphael began the room, but he used assistants more and more, and it was they who finished it. The Fire in the Borgo has Pope Leo IV extinquishing a fire in the Borgo neighborhood bordering St. Peter’s. We can see old St. Peter’s in the middle. The Pope (likeness of Leo X) appears to the right of this in a Serlian loggia. The highlight for me here is the man saving an old man, with young child in tow, certainly taken from the Aenied, and Aeneas saving his father Anchises and his son Ascanius. I don’t like the naked man letting himself down the wall—here Raphael descends into the imitation of Michelangelo. By the time of this painting Raphael was heavily relying on his student Giulio Romano (1492-1546). We know Giulio made the impressive woman carrying water. The art critics see the post High Renaissance “mannerism” creeping into Raphael’s work here. I have never been able to define the term mannerism, but when I try to, I think of repetition and lack of originality. |  |  |  | Giulio Roman's famous Woman Water-carrier. Look how she doesn't drop the jug but gasps in horror. | More Leo’s on the next two walls —the Coronation of Charlemagne by Leo III and the Oath of Leo III, both regarded as not the master’s best (if he even did them). Again the likeness of Leo X. Leo III took an oath of purgation before Charlemagne to deny the accusations of abuse that had been brought against him. We can see his accuser (oddly the likeness of Lorenzo de Medici—the “Magnificent”). The Emperor has the likeness of Alfonso di Ferrara. | |

On the last wall we have The Battle of Ostia, with the Christians defeating a group of Muslim pirates in 849. The Muslims had sacked and desecrated St. Peter’s and St. Paul’s in 846 and Leo IV promptly had a wall built around St. Peter’s and sent what fleet he had to defend the coast. Again Leo X has his likeness painted! This last work was entirely by Raphael’s assistants.

Perugino in 1506 and 1507 had painted the vault of the Incendio, and Raphael left it alone.

| Perugino--God the Father, Jesus and the devil, the Trinity and Apostles, and Jesus with Justice and Grace | |

The last hall in the Raphael’s Stanze is not Raphael’s at all, but belongs to Giulio Romano and Giovanni Penni (1488-1528). Leo X commissioned Raphael to decorate the large audience hall in the spring of 1517. The pope and the artist conceived the idea of four scenes from the life of Constantine, the first Christian Emperor. Raphael had made cartoons before he died in 1520, and his two students made use of these as best they could. The Battle of the Milvian Bridge dominates the room, and Constantine dominates the scene. Here we have the “studied, lavish tone” of Mannerism. Romano painted himself (the man raising his hand to his cap) into the Donation of Rome, which memorializes the mythical Constantinian donation of Rome and Italy to the Pope. The Baptism of Constantine (his Baptism actually happened at Constantine’s death in Ephesus) and the Vision of the Cross (Constantine sees the Cross of Christ in the clouds and receives the admonition “In this sign you will conquer”). Leo X died unexpectantly in 1521, succeeded by the austere Pope Adrian VI (1522-1523), and it wasn’t until the elevation of another Medici Clement VII (1523-1534) that the frescoes were completed (we can see the emblem of Clement VII on the frieze accompanying The Baptism and the Donation).

If you have a chance, I would retrace your steps and just go through the Stanze quickly one more time, this will ground you better in the twelve wall scenes. A memory to be kept in a special place.

|  | |

Our next walk takes us to the Sistine Chapel!!!! | | | | |