|

The Pharoah Pursues the Israelites The Cypress Doors of Santa Sabina |

|

The Aventine Hill--the Ripa Rione Part 2 | |

|

The Ripa Rione extends to include the Aventine Hill (but not the “little Aventine” across the Viale Aventino, which is in the Saba Rione). The name Aventine probably comes from “hill of the birds,” an allusion to the contest between Romulus and Remus as to who would rule the city. Romulus sat on the Palatine to observe the auspices and saw twelve vultures, and Remus sat on the little Aventine and saw but six. Each interpreted the augury in his favor, and Remus leapt across the boundary of the Palatine only to be slain by Romulus.

The Aventine seems to be the highest of the seven hills of Rome and is certainly the most picturesque and tranquil. The large Rose Garden of Rome is here, across from the Circus Maximus, and the Jewish cemetery is close by. The cliffs of the Aventine overlook the Tiber and give wonderful views of the Janiculum and the dome of Saint Peter’s. There is a cave on the side of the Aventine below Sant’Alessio that was the legendary home of the fire breathing giant Cacus, son of Vulcan. Hercules pastured his cattle near Cacus’ lair, and while Hercules slept Cacus stole eight of them, dragging them by their tails so as to trick Hercules into thinking they went the opposite way. But the remaining cattle pointed by their lowing in the direction of Cacus’ cave, and Hercules stormed in and strangled Cacus before the monster’s fire could consume him. The thankful Romans erected a temple for Hercules at the base of the Palatine, near what became the ancient Porta Trigemina of the Servian wall.

The Sabines made the Aventine their home after they were induced to live in the city, their women folk having been stolen by Romulus’ men. The Sabine King Titus Tatius ruled jointly with Romulus for five years and was buried here among the famous laurels of the hill. The fourth King of Rome was Ancus Marcius, and he subdued many of the Latins, built a wall around the Aventine, and settled the defeated newcomers there. This was the origin of the plebs, who became the opponents of the patricians on the Palatine.

The Aventine continued over time to be the headquarters of the plebian class; the patricians avoided the hill out of the superstition associated with the fate of Remus. In 416 BC the Tribune Icilius carried a law conferring all the public lands on the Aventine to the plebs, and a housing boom ensued. The hill was now brought into the pomoerium or formal boundary of the city. It came to be called the “hill of the people.” In Imperial times the reputation of the hill changed dramatically, and it became the favorite for the wealthy who put up their mansions among luxurious new temples, including ones for Luna, Diana, Liberty, Juno, and Minerva, and a grand bathhouse, the Thermae of Decius. Both Trajan and Hadrian had homes here before they became Emperor.

When the city depopulated, the Aventine like the other waterless Roman hills was largely abandoned, left to the monastics, the fortress builders, and the encampments of occupying hordes and armies. The Aventine is today once again repopulated, centered on the churches and convents of Santa Sabina, Sant’Alessio, the Priory of the Knights of Malta, San Anselmo, and Santa Prisca.

| |

We begin our walk along the Tiber on the Northwest corner of the Rione, going south on the Via Santa Maria in Cosmedin. On our right we admire for a moment the Fountain of the Laundry Tub, once hard by the Cosmedin, made in 1717 for Clement XI and moved here when Mussolini made the Via Petroselli. It was used both by horses and for laundry washing. Its long tub is the only one of its kind in Rome. The lion is the only adornment and he is certainly lonely, and very unhappy the authorities allow him so little water. The quays of the Ripa port would have begun here below the Aventine and continued down river past Mount Testaccio and extending onto the right bank. |  |  | We turn left on the Via Rocca Savella, a walkway thankfully, and we trudge up the hill to the steps of the Giardino d’Aranci o Parca Savello, the gate sometimes closed requiring us to continue to the left to the Via Santa Sabina. The Parco Savello is really a very large terrace overlooking the Tiber with a marvelous view of Saint Peter’s, and it is full of orange trees and pines. Many times there will be a solitary musician sitting on the wall. I once saw a monkey-grinder here. There are always thousands of noisy parakeets here, not sure how they got here. Probably a gift from a faraway prelate to the pope who allowed them to escape. There is a special fountain treat for us here. In 1936 Mussolini set up prism fountains throughout the city, giving them a faucet in the form of the Shewolf. These were white travertine prisms, very simple and elegant, and which had a bronze shewolf for the faucet. There are only two survivors, one here! The other is at the park near the Porta di San Pancrazio. |  |  |  | From the park we go to the basilica of Santa Sabina. We of course see the Basilica as we walk through the park. It is a huge three-story building, perfectly proportioned, with a round apse on the north, and a magnificent tiled roof above the brick windowed walls enclosing the nave. Most of Rome’s churches cling to the buildings next to them. The Sabina stands majestically alone, and we can view all sides of her as we go through the park. |  | To get into the church we pass through the Piazza Pietro di Illyria. Here another fabulous Roman fountain—the Bocca di Sabina. The grotesque face we see was made by Giacomo della Porta, the fountain maker of Rome, close to the end of the sixteenth century. It was made for the large drinking water trough for livestock that was on the Forum by the Arch of Septimius Severus. When that trough was taken in the 1800’s for the Fountain of the Dioscuri on the Quirinale, the grotesque was moved to a different trough, this one on the right bank of the Tiber, directly across from San Giovanni Battisti dei Fiorentini. Then when the new flood retaining walls were put up on the Tiber at the end of the nineteenth century, the fountain was put in storage. In 1936 the fountain was re-erected where we see it today. | Two of my children 2006 version admiring the Bocca in the Piazza di Pietro di Illyria |  |  | |

How did Santa Sabina come to be here? Saint Jerome’s friend Marcella (he praised her as the “glory of Roman women”) had her mansion on the Aventine, and here she kept in an anchorite cell the relics of Saints Sabina and Seraphia, who had been martyred for their protestation of Christianity under Hadrian c125. In 410 Alaric and his Visigoths sacked Rome, and the Palatine with its grand mansions was looted and burned, including Marcella’s home. Marcella and her adopted daughter Paula were not treated well by the Goths, as they had no money to give them as they had previously given it all to the poor, and they fled down the Via Ostiensis to the safety of San Paolo, never to return. Rome by some miracle recovered from the sack, and the Deacon Peter of Illyria (Dalmatia), perhaps with inspiration from Jerome, his fellow Illyrian, decided to build a basilica on top of the remains of Marcella’s mansion.

The basilica we see today is Peter’s, faithfully restored in the twentieth century by Professor Antonio Munoz, built according to the rules of Augustus’ architect Vitruvius, and although the height of the nave is not equal to the width, all the other rules were followed. Thus the height of the columns is nine and one half times the diameter at the base, and the intercolumnar spaces are five times the diameter.

We will come back to the Cypress Doors in the vestibule, but we first want to admire this early Christian church.

This was once how all churches in Rome looked. There is not a single ounce of baroque here. The color is a soft silver, the columns are exquisite with their two levels of fluting, Parian with identical and perfect Corinthian capitals. Buildings in Rome can be dated by their capitals. Vitruvius wanted the capital to be the same height as the diameter at the base. As time went on this proportion deteriorated and capitals gained considerably in height relative to the base. Here the height of the capitals exceeds the base by one-seventh, dating the capitals to an intermediate period after Augustus but well before the sack of 410. This dating conflicts with claims that the columns were actually made by Peter the Illyrian, coming from the marble works still functioning on the Aventine, who were still obtaining marble from the Ripa marble port, the Marmorata. The name of the column maker is inscribed at the base of the third column on the left, one Refenos.

The ceiling is a restoration, at one time we could see the timbers. The Romans usually put up flat coffered ceilings that covered the timbers like the one we see here.

|  |  | |

The colonnade here is unusual for a classical building, normally we would expect an architrave. But Peter was from Illyria, where arcades were in use. The inlaid frieze of pietradura originally extended up to the windows (taken down by Sixtus V). The marble revetment has beautiful colored marbles with chalices, patins, and shields. The red and green pietradura of porphyry has the insignia of each of the companies of the Roman legions. The curved and painted symbols on the sides of this are spurs, certainly put up by Peter in honor of his father, who was a well-known horse dealer who furnished the famous Illyrian horses for the Roman legions. Midway down the nave we will find three plaques which bear the authentic standards of the Illyrian companies of the Roman legions.

Sixtus V, though he meant well and was a city builder and restorer, was unfortunately not kind to the Sabina. He took down the apse mosaic, and also the mosaic on the triumphal arch which had twelve medallions (imagine clyptae) of the prophets and Apostles, and the mosaic above the arcade, and large pieces of the mosaic on the counter-facade. In the apse and on the arch poor fresco substitutes were put up.

The choir is a ninth century addition, but it was built with the same simplicity we see in the nave. There are two ambones—that on the left was used by the Subdeacon to sing the Epistle, the one on the right used for the singing of the Gospel by the Deacon.

There are numerous floor tomb slabs in the nave and aisles. In the middle is the general of the Dominican Order, Munoz de Zamora (d 1300). More fascinating are the troops of the Holy Roman Emperor Henry VII who came to Rome in 1312 thinking to be crowned at Saint Peter’s. The adherents of the papal side (the pope then in Avignon), called the Guelfs, had other ideas. They were opposed by the imperial side, the Ghibellines (Colonna and Orsini families). The battle raged for weeks and culminated in Henry’s storming of the barricades put up in front of Saint Peter’s. The German tombs we see in Sabina, mostly on the left, are the graves of the fallen German soldiers, buried here on the Aventine, where Henry headquartered.

The clerestory windows are glazed with thin mica (originally selenite) with circles, squares, and lozenges in the perforations. The ones in the apse are most unusual for Rome (Sixtus covered them up in the counter-reformation Borromean desire for less light, fortunately reopened in the 1924 restoration of Professor Antonio Munoz). The earliest of Christian churches had immense amounts of light streaming in, and the Sabina followed their lead.

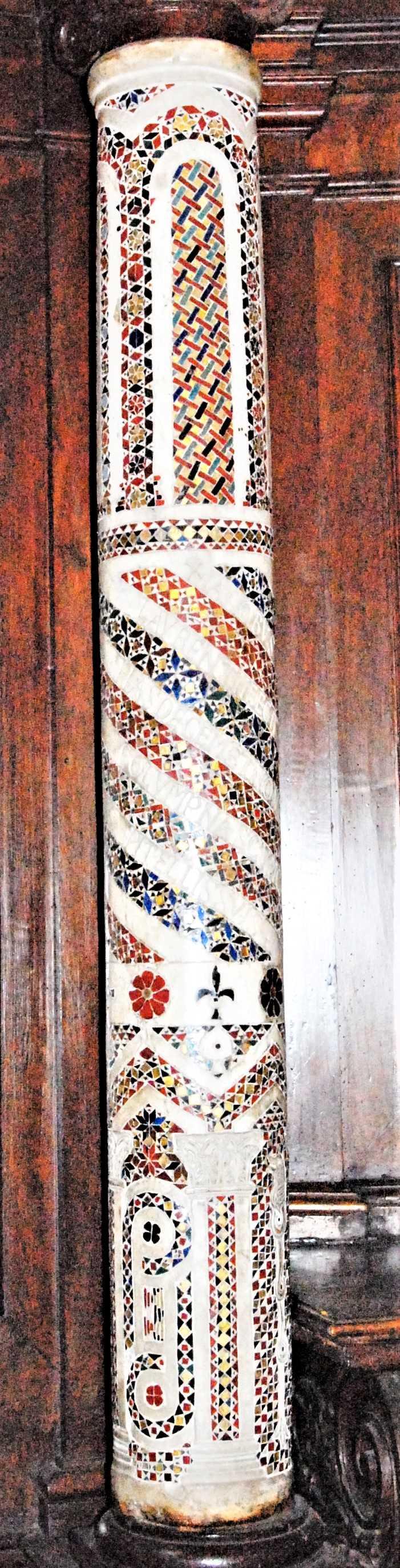

|  | On the right upper side of the nave is the tomb of Cardinal Auxias de Podio (d1483), who gave us this admonition: VT MORIENS VIVERET VIXIT VT MORITVRUS, “In order to live after dying, he lived as one about to die.” | There are two precious pieces of Cosmati work here. First is the aumbry, or receptacle for the holy oils, on the left. We are told that this was made from a single block of marble by the Cosmati Father Pasquale, whom I have not encountered elsewhere in Rome. Then on the left is a little side altar for Dominic, with a modern painting of the saint, surrounded by Cosmati, with a little pediment on top. |  |  |  | |

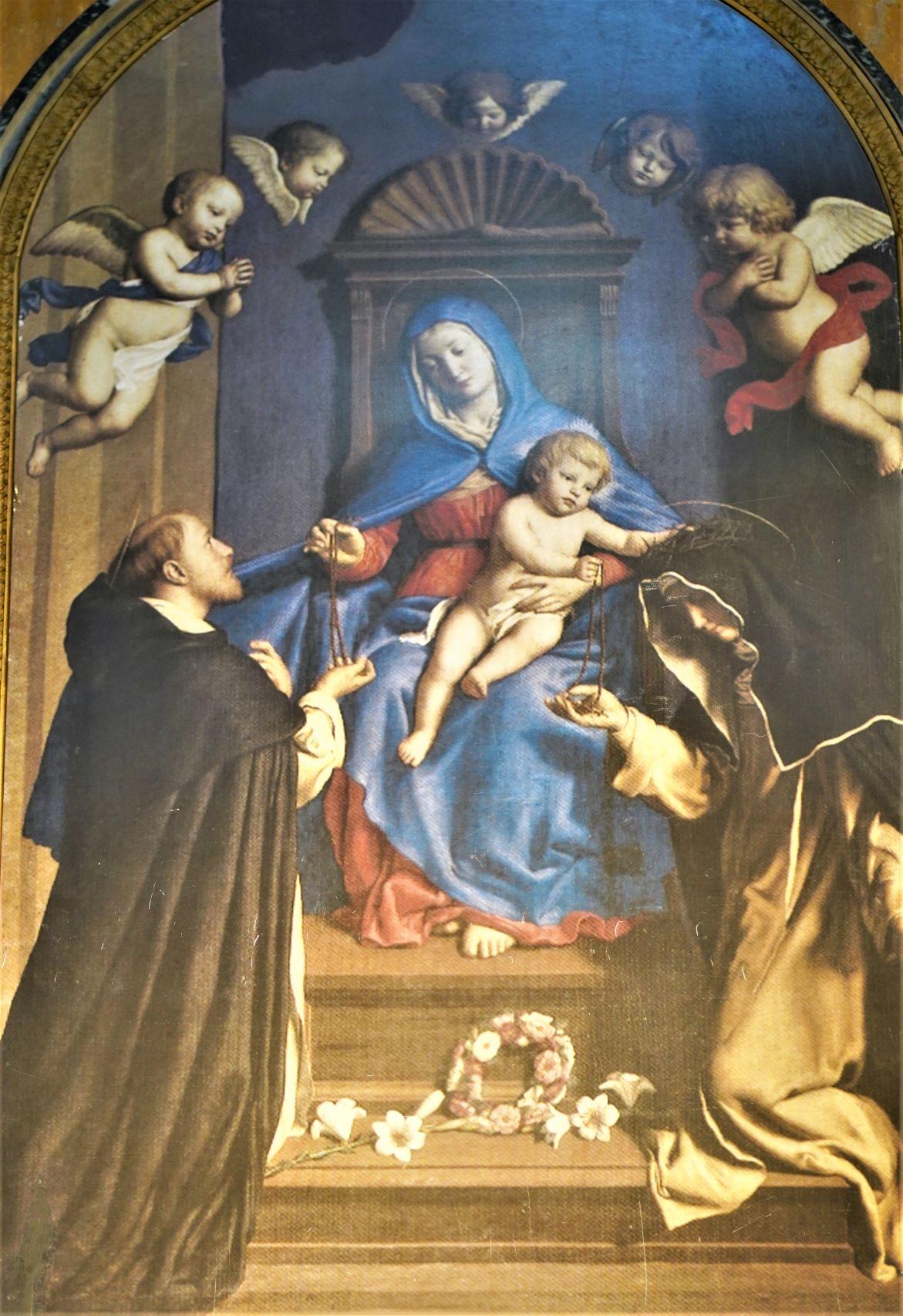

Next we go to the Chapel of the Blessed Sacrament, also named for Catherine of Siena. Here we have Our Lady and the Divine Child Giving the Rosary to Saints Dominic and Catherine, also called La Madonna del Rosari, by Gian Battista Salvi, known as Sassoferrato (1608-1685). Dominic received a vision of the Institution of the Rosary in his cell in the convent here. The Virgin also commanded him to plant an orange tree!. Dominic had brought the tree from his native Spain. The orange tree was unknown to the Romans, Dominic brought it as a gift for Honorius, whom he knew to be an avid botanist. Catherine also receives a rosary from little Jesus, and she wears a crown of thorns.

You will always encounter a nun praying in the chapel now, she is on guard for theft. The painting was stolen in 1902, recovered by a policeman posing as a buyer. It was stolen again in 2006 by a man on a bicycle, but it was recovered on the same day. We were in Rome at the time and the theft understandably created quite a ruckus. And so now the ever present nun.

Restoration has made this painting a bit more crisp than it should be, but it is still a beautiful work. Sassoferrato (named for his town in the Marche) was a student of Domenichino and also Annibale Caracci, and trained with Guido Reni who is said to have influenced him much. He loved and tried to imitate Raphael. No baroque flamboyance for him. He is best known for his devotional paintings. He has a Madonna and Child at San Clemente a copy of which I am sure you have seen in your church, convent or parish school.

|  | |

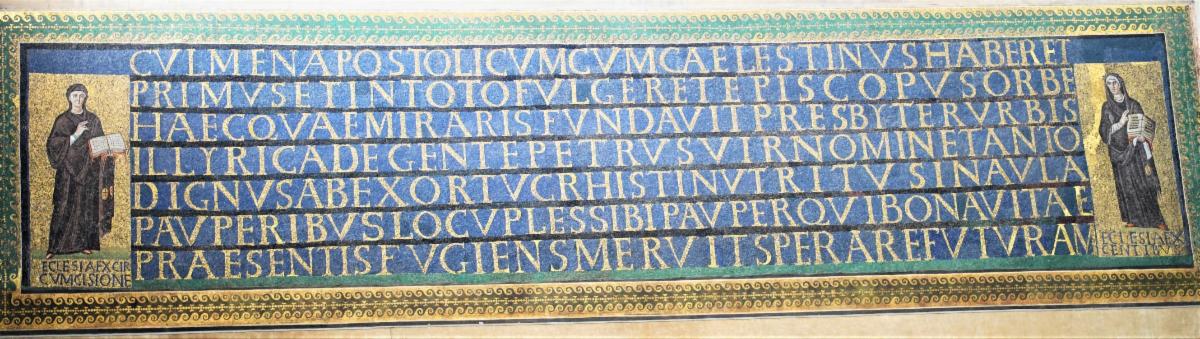

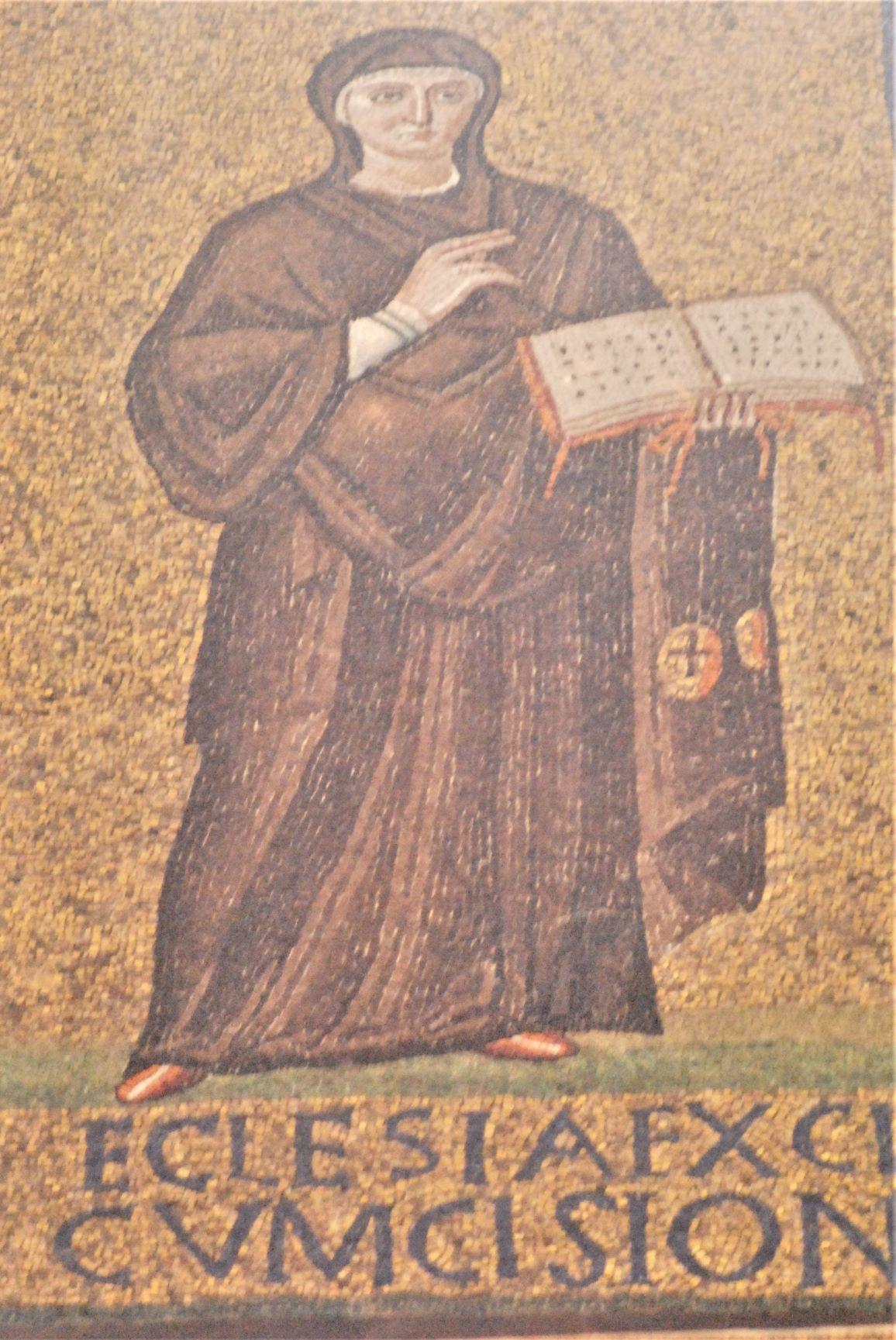

Now we turn around to see on the counter facade the mosaic made at the time of the making of the basilica and the Council of Ephesus-- the Mosaic of the Circumsicione (the old church, the Jewish people) and the Gentibus (the new church, the gentiles). There is a phrase in the inscription which has become famous in our church: PAVPERIBUS LOCVPLES SIBI PAUPER QUI: “rich to the poor, poor to himself,” a honor given to Peter the Illyrian. Note that the two matrons are giving us the Roman rite with their right hands—first two fingers up, next two down, thumb up.

The Roman classic style was still evident here, with full bodied figures, natural and graceful, each face individually modeled, clothes with natural and rich folds. This mosaic is contemporary with the mosaics in the nave of Santa Maria Maggiore, and an oddity is that the Maggiore once had a similar inscription on its counterfacade which was taken down, and the Sabina used to have mosaics lining the nave as at the Maggiore, taken down. The mosaic at the Sabina once had Peter and Paul, and the four beasts of the Evangelists, lost under Sixtus V.

|  |  | |

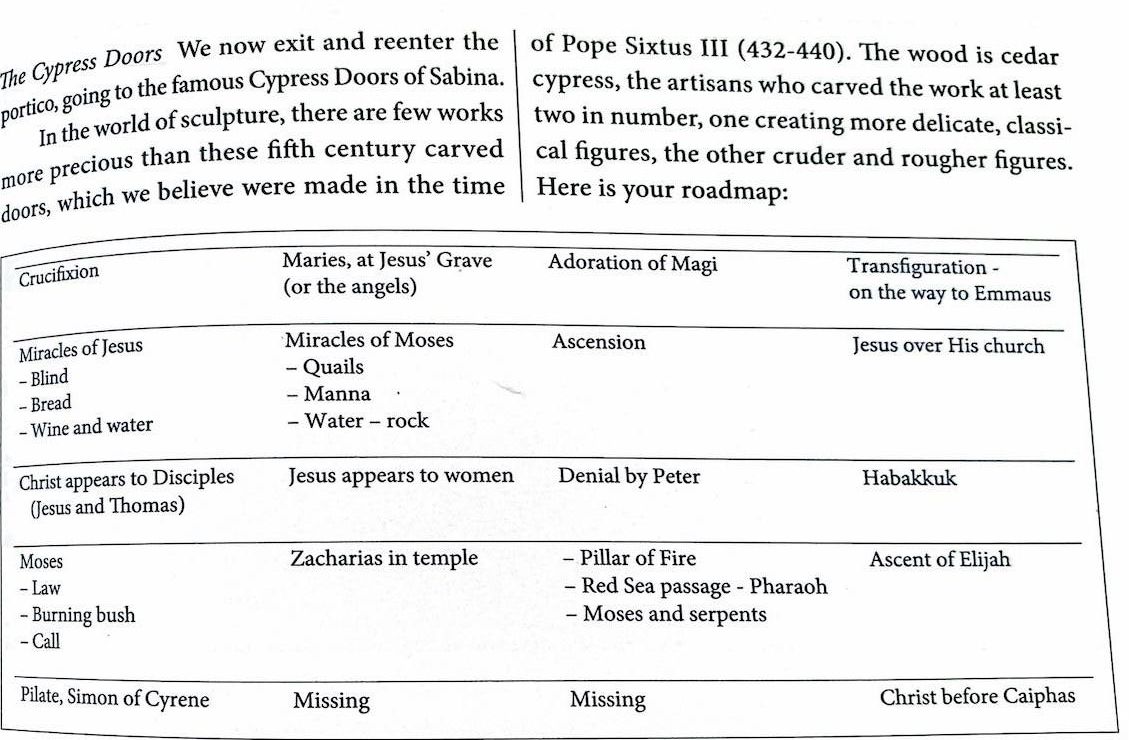

And now for the Cypress doors. The portal carrying the cypress doors is comprised of three single blocks of beautifully carved marble, a perfect example of an Ionic doorway from ancient times. The reliefs of scenes from the Old and New Testaments are cut from cedar cypress. In the upper left we have the Crucifixion with Jesus between the two thieves. Early Christians did not depict the Crucifixion, seeing it as a denial of Christ’s victory. Which makes the dating of these reliefs difficult. Most believe, the Crucifixion notwithstanding, that they date to the pontificate of Pope Sixtus III (432-440). If so, this is the earliest known surviving representation of Christ Crucified.

There were two artists involved, one did crude work, the other exquisite work. You can easily see which artist did which panel. I give you below a diagram describing the panels. My favorites are the ones with the bigas in them—the Ascent of Elijah, and Pharoah Engulfed by the Sea. The artist, working with a difficult medium, gives us classical figures in the round, with great cloaking, and magnificent horses, all in good proportion. The doors have been damaged over the centuries and some panels lost (there were originally twenty-eight, only eighteen survive). You can see the lower panels are now protected by plastic. The wood surroundings are of younger replacement wood.

|  |  |  |  | Excuse the bend--photo from my guidebook Sacred Places |  | |

In the vestibule we stop to look through the keyhole at the orange tree planted by Dominic (orange trees were subsequently planted at the Parco Savello too). I am not sure orange trees can live that long. The story goes that the original tree died but a new root sprang up giving us the one we see today. The orange Dominic brought from Spain was of the bitter type that is so good for marmalade. Saint Catherine of Siena sent five candied oranges from this tree to Urban VI in 1379.

The columns in the vestibule are fifth century originals. There is a grating in the vestibule that lets you see down to the Imperial mansion upon which Peter built his church.

If you can get into the convent by all means do so. There you will find Dominic’s room, where he received Saint Francis. Saint Thomas Aquinas also lived here for a time, a refuge from his mother who was trying to keep him from the Dominicans. The inscription over the door includes this admonition: “Newcomer, take heed. Here of old the most holy men Dominic, Francis and Angelus the Carmelite spent night-vigils…”

Sabina is the headquarters of the Dominicans. In medieval times, the Savelli family owned the Basilica of Santa Sabina, its convent and the adjoining complex. Pope Honorius III (1216-1227), a Savelli, made Dominic the Abbot of Sabina when the saint came to Rome (he also appointed him master of the papal household). Dominic was so successful as Abbot that the pope made over the entire Sabina property to him.

Sabina had long been important in the life of the Church of Rome. Gregory the Great read two of his famous homilies at the Sabina, and instituted mass here on Ash Wednesday, making it the first of the Lenten station churches he inaugurated. In 1285 a conclave was held at the Sabina to elect the successor to Pope Martin IV (1281-1285), but was broken up by a malarial outbreak, which killed six cardinals on the spot. Cardinal Giacomo Savelli refused to leave, keeping the malaria at bay with large chamber fires. He was rewarded with his election as Honorius IV (1285-1287). Aquinas was here, Francis was here, Catherine of Siena was here, Norbert was here, Raymond of Penaforte was here. Thank you Peter of Illyria!

|  | |

Now having ended our visit to the Sabina, we head back to the Via di Santa Sabina and turn to the right to go the neighbor, San Alessio. Before we stop at the church we visit the little park of San Alessio, which has in it yet another of Rome’s small fountains. This one was once in Piazza Rusticucci near Saint Peter’s, but the Piazza and the fountain were taken down in 1937 to make way for the Via Conciliazione. All that remains of the fountain is a rock pile with a large eagle holding a small basin. The inscription on the basin recites the demise and translation of the fountain. If you would like a quiet rest, this little park is for you. | |

|

Saint Alessio is the Roman version of the Prodigal Son, except that Alessio didn’t leave for sport and fun, he fled because as a pious Christian he couldn’t accept the married life his father Euphemian wanted for him. He lived as a pauper for fourteen years in Mesopotamia, and gained notoriety for his sanctity. Again he was compelled by his piety to escape, and he returned to Rome, and in order to avoid dependency on others he decided to live under his parents’ steps and eat the scraps servants threw out. He was correct in his assumption that his beard and appearance would not reveal his identity to Euphemian, who saw him daily under the steps.

He spent his days in ministry to those even poorer than himself. He lived in privation for seventeen years and then his health failed him and death approached. The pope had a dream of an unknown saint dying in Rome under a flight of stairs, a dream he shared with the Emperor who in turn mentioned it to Euphemian who immediately understood this to be the poor man who had lived under his steps for so many years. Euphemian went to Alessio only to find him already dead, holding in his hand a note Alessio had written to him, explaining all. All Rome went into mourning, and Romans ever since have revered Alessio, a man who had twice refused a fortune and chosen instead service to the poor. Alessio is appropriately patron saint of beggars.

The legend is that Euphemian’s house, and the steps Alessio lived under, were here on the Aventine where Alessio’s church now stands. The façade and forecourt are plain and unremarkable. Each time I visit food is being distributed to the poor in Alessio’s name. The campanile is very beautiful and far outshines all else here.

|  | We go inside and turn to our left to see the steps of Saint Alessio! Then we tour the pavement of the church, Cosmatesque. The pavement may not date to the Cosmati. There is original Cosmati in the Bishop’s throne, which has two columns that came from San Bartolomeo all’Isola. JACOBVUS LAURENTII signed one of the columns (I couldn’t find the signature). Try to see the crypt, it is said to have relics of Thomas Becket (d1170), and also the pillar to which Saint Sebastian was tied when he was shot with arrows. |  |  |  | From Alessio we go to the Piazza of the Knights of Malta, situated on the expansive laurel grove of the Aventine, designed by Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-1778) in 1765. The famous keyhole (the Buco della Serratura) at the entrance to the priory is surprisingly never busy (unless a busload of Chinese arrive). You can look through the keyhole and see through the garden the dome of Saint Peter (the Romans call it the Cuppolone). If you can get in to see the tombs of the Knights and the splendid garden (a forest of old bay trees, plus palms and a famous old pepper tree), you should. The church here, Santa Maria del Priorato (by Piranese), is said to be unremarkable, but I have not found my way in to see. The tombs of the Knights of Malta are certainly the special feature. | The uninspiring Piazza of the Knights of Malta. The Priory and the famous keyhole on the right. On this day anyway no line to peek through to see Saint Peter's dome. Saint Anselmo's is on the Piazza. | A photo through the keyhole. Saint Peter's dome is there I assure you. The hedge is beautiful! | San Anselmo is next, but I must report that this is a modern church (1900), with nothing of interest for us. Anselmo (1033-1109) was a philosopher, credited by some as the originator of the ontological argument for the existence of God. He was Archbishop of Canterbury 1093-1109, buried at Canterbury cathedral. I have not learned why he was given this church on the Aventine. | From Anselmo we trudge back to Santa Prisca, retracing our steps on the Sabina taking a right on the Via Alberto Magno, going down a few blocks to the Santa Prisca on our left. Prisca and her husband Aquila were friends of Saint Paul, and gave him shelter in their home here. They may also have had Peter with them. Paul mentions them in his sixteenth paragraph of his letter to the Romans (“Greet Priscilla and Aquila, my helpers in Christ”). The columns here are ancient. The crypt is inaccessible unless you are very important, which I regrettably am not. There is an ancient Roman nymphaeum here. That too I was not fortunate to see. It has all the usual imagery of the pagan cult with the gory bull and all. At the time the Christians built their church here on top of the Mithraeum there was an ongoing conflict with the Mithraens and so they smashed all the idols. In the twentieth century excavations these were found and restored and they are now available to see on the tour. | |

On our next walk we continue on to the "little Aventine" in the Saba Rione, where we will see San Saba, a thriving parish church, the wonderful residential neighborhood of the Little Aventine, Santa Bibiana, and the Baths of Caracalla.

Copyright Greg Pulles 2023 All rights reserved.

| | | | |