|

Arnolfo di Cambio's famous Hanging Angel Thurifer from the inside of the San Paolo Baldacchino |

|

Saint Paul's Outside the Walls--the Tomb of the Apostle Paul | |

Saint Paul's, Baldacchino of Arnolfo di Cambio, Cloister of the Cosmati, Tre Fontane | |

Today we visit the Patriarchal Basilica of Saint Paul’s, in the early Christian Church under the formal care of the Patriarch of Alexandria, and until the time of Henry VIII the church of England. If we are following the pilgrims' path of Philip Neri, we walk from the Catacombs of Domitilla on the Via delle Sette Chiese west toward the Tiber. We will pass a church for Philip on the right side, go through the Largo Sette Chiese, and eventually find ourselves on the Via Ostiense, where we will see the Basilica on the left. The Blueline Subway will also take you directly there. | |

|

When in Jerusalem c60-2, Paul was arrested after the Jews complained to the Roman authorities. Paul was taken to Caesarea, where he was held for some two years. When the Roman Governor of Judea Porcius Festus decided to send Paul back to Jerusalem, Paul invoked his right as a Roman citizen to “appeal unto Caesar.” Paul, accompanied by the Roman Centurion Julius and the eleventh legion Augusta was then taken by ship first to Adramytium and on to Fair Havens. He was then shipwrecked on Malta, thereafter resuming his journey to the Bay of Naples, landing at Pozzuoli. From there Paul was taken on the Via Campagna to Capua, and from there down the Via Appia to the Forum Appii, Tres Tabernae, and Bovillae, entering Rome through the Porta Capena.

Julius turned Paul over to Afranius Burro, prefect of the Praetorium, who gave him a sort of bail, with freedom to preach and evangelize under the supervision of a police escort. When no accuser came forth to challenge Paul’s appeal to the emperors, Paul was given a trial probably at the end of the year 63, in the “Consilium Priciois” and then restored to full liberty as a Roman citizen.

Paul was in Rome for a second time in 66, again charged, and this time imprisoned. He was condemned to death and led out the Via Ostiensis. The matron Plautilla encountered him on the way to execution, and gave him her shawl to wipe his face (he returned it to her in a vision). Paul was executed at the Aquae Salviae on the Via Laurentina on June 29, in perhaps 67 or 68. The matron Lucina (who seems to have been a heroine to many Christian martyrs from Apostolic times until the fourth century!) claimed Paul’s body, and laid it to rest in a plot she owned just outside the second milestone from Rome, property on the right or west side of the Via Ostiensis. The plot was within the confines of a pagan cemetery, and the Apostles’ tomb was close by a pagan columbarium.

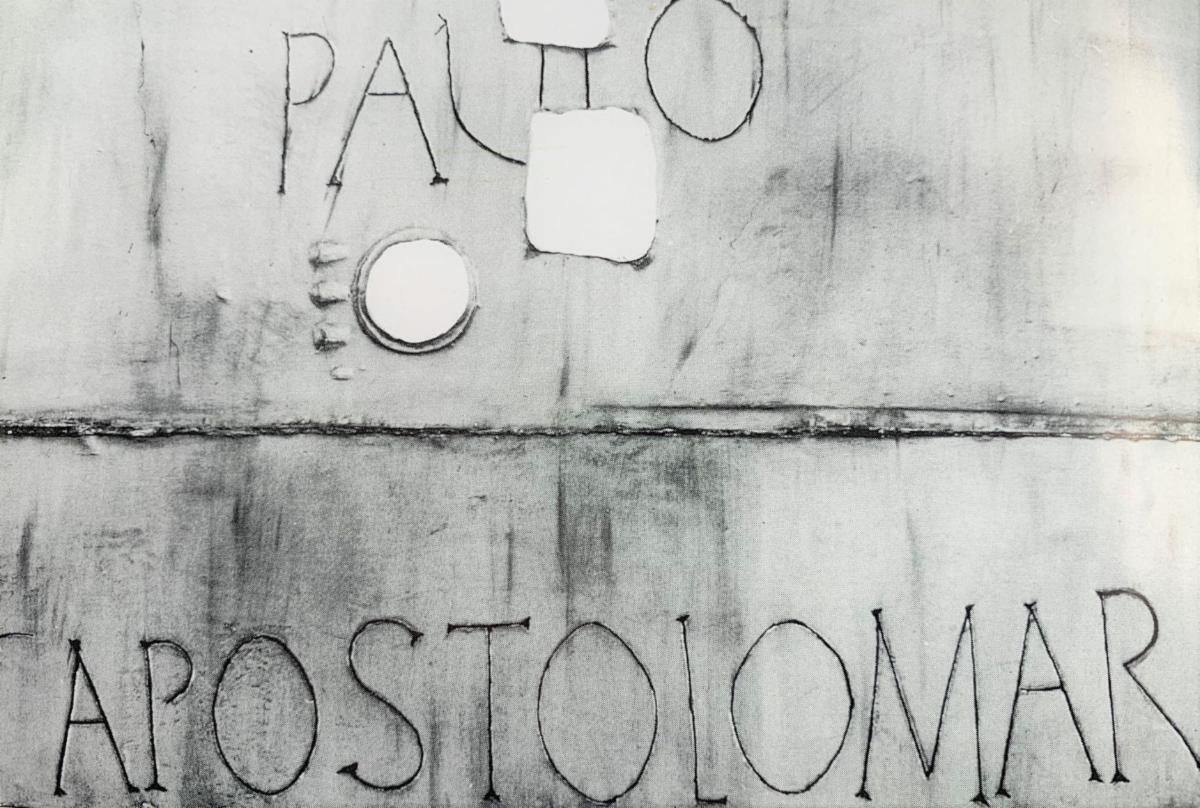

At some later date Paul’s relics were placed within a white marble sarcophagus, over which two marble slabs were placed, one bearing the word “Paulo” and the other the words “Apostolo Mart.” We know from the use of the dative and not nominative case of the Latin that this lettering was not a simple funerary inscription but rather a dedication of some sort. We also know from the unevenness of the letters and their slightly upward tilt that the inscription was added after the marble slabs had been placed in position. The tomb may have been enclosed, either from inception or perhaps sometime in the first century, with horizontal grating on three sides, perhaps part of a tropaion or above ground tomb shelter.

| |

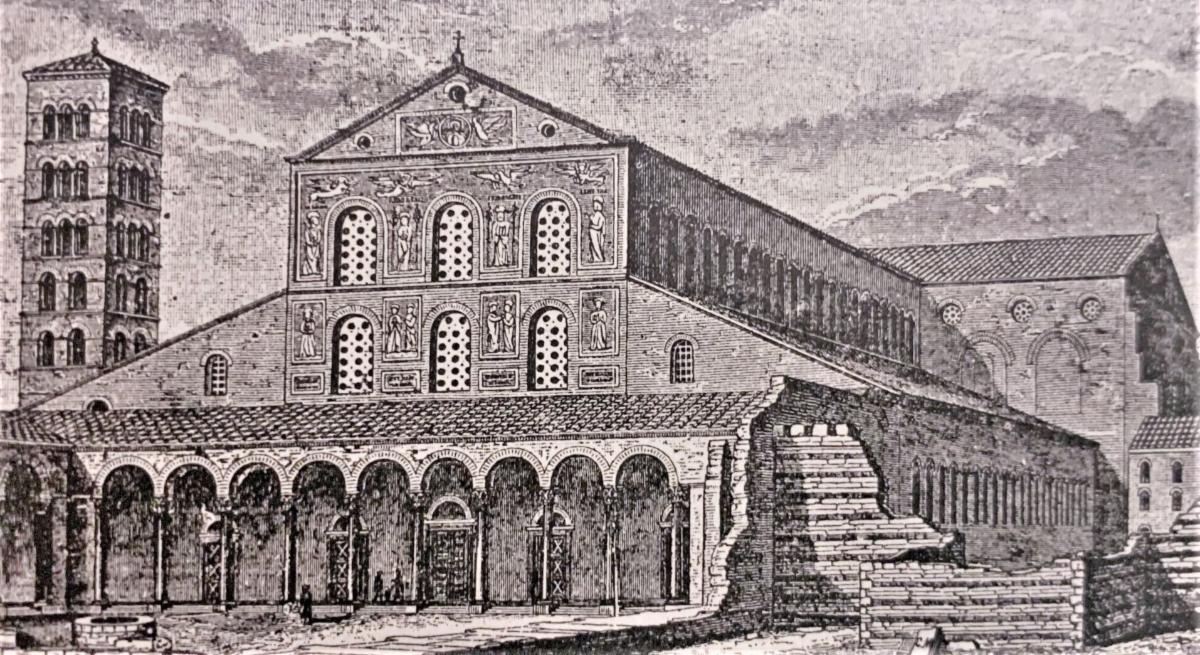

Constantine constructed a basilica for Paul, one that was considerably smaller than the one he erected for Peter, no doubt due to the constraint of the Via Ostiensis and the need to have the apse of the church, and its entrance, face the east in keeping with Jewish and Christian tradition.

The Liber Pontificalis, or Book of the Pontiffs, a work primarily of the fifth and sixth centuries, tells us that Constantine gave Paul a new coffin of bronze, with a gold cross of 150 pounds placed on top of it.

The Constantinian Basilica proved inadequate for the pilgrims, and due also to the late fourth century sentiment that Paul was as important to the Church as Peter, the Emperors Theodosius the Great (379-395)(the last Emperor to rule over both the East and the West), Valentinian II (383-392)(Emperor of the West) and Arcadius (395-408)(Emperor of the East) determined in 386 to build a new and more proper Basilica for the Apostle. Arcadius, son of Theodosius, was just nine at the time, and Valentinian II (son of Valentinian and whom Theodosius had rescued from the usurper Magnus Maximus in 383) was just fifteen, and so this was most certainly the initiative of Theodosius, undertaken perhaps at the instigation of Saint Ambrose (339-397), bishop of Milan, who held great sway with Theodosius. We find the name of Pope Siricius (384-399)(the first bishop of Rome to be called pope) in the dedicatory inscription in one of the columns of the basilica, now in the north vestibule: SIRICIVS EPISCOPVS (ALPHA Christogram OMEGA) TOTA MENTE DEVOTVS.

Theodosius was bound not to move the Apostle’s tomb, and also was obligated to center the tomb on the apse. In order to achieve the size he needed, and not move the Via Ostiensis, he was forced to violate the third cardinal rule of Christina Basilican architecture: he had to reorient the nave and face the apse and the entrance to the west, and not the east.

|  | |

The massive five aisled basilica with massive transepts that Theodosius constructed ran from the road to the tomb, and the nave extended to the west toward the Tiber. In order to prevent flooding, the floor of the nave was raised about .4 metres, the transepts a metre more. This meant that Constantine’s memoria for Paul disappeared below the floor level. The two floor slabs with “Paulo Apostolo Mart” would have been pried loose and put in their current position below the altar. The altar would have faced the nave for the celebration of the sacred mysteries, and a tubular connection provided for pilgrims who entered from the east who needed access to the area directly over the tomb.

A circular aperture was cut in the rear pavement slab which contained the name of the Apostle, and this reached down to the apostle’s tomb. A movable metal cover was laid in position over this—traces of this cover are still visible. The faithful would perform two customs- they would kiss the metal covering and pour down balsam oil onto the sarcophagus. Then they would lower their brandea or linen cloth to touch the tomb, hoping the cloth would weigh more upon retrieval signifying their prayer request had been granted. The actual body of the saint was a first order relic, the sarcophagus a second order relic which had touched the body, the brandea which had touched the sarcophagus a third order relic. Over time the balsam oil tradition was dropped in favor of the brandea.

|  | |

The Basilica was perhaps the most magnificent church ever constructed. It had a wide and tall nave with light from forty-two windows, double aisles on either side, an atrium with porticoes, and a very large apsed transept. The columns included fluted pillars of white marble with violet-blue veining, taken from the tomb of Hadrian, and no expense was spared for the marble pavement, the baldacchino, the gilded coffered ceiling, and the fresco decoration of the clerestory walls with scenes from the lives of Peter and Paul and the Bible, and the mosaic of the triumphal arch giving the Four and Twenty Elders giving jeweled wreaths to Jesus.

The Liber Pontificalis records in the life of Leo the Great (440-461) that the pope “renewed St Paul’s after the divine fire (lightning).” The inscription of Galla Placidia, daughter of Theodosius, on the Triumphal Arch records the admiration for Leo’s repair work, which included twenty-four shafts of purple pavonazzetto marble with luscious Corinthian capitals.

Over time the Church received extraordinary additional decoration, including the Byzantine-Venetian apse mosaic of the early twelfth century, the Cosmati Cloister of the thirteenth century, and the thirteenth century façade mosaics and nave frescoes of Pietro Cavallini, and the Baldacchino of Arnolfo di Cambio.

The glorious classical church, larger than Old St. Peter’s, and the largest church in Christendom until new St. Peter’s, miraculously survived the Gothic and Vandal Sacks of 410 and 455. The tomb of the Apostle was however greatly damaged in the Muslim sack of St. Peter’s and St. Paul’s in 846. Benedict III (855-858) recorded that the Muslims destroyed the tomb, but the Italian archaeologist Rondolfo Lanciani gives the hopeful analysis that because the marble slab with Paul’s name on it seems to have retained its location under the altar, it is likely that the Muslims didn’t destroy the tomb, although they most probably made off with the bronze enclosing casket of Constantine.

After the Muslim Sack Pope John VIII (872-882) constructed Johannipolis, a fort city centered on the three roads that the Muslims could use to attack Rome—the Ostia, the Laurentum, and the Ardea, and commanding also the waterway by the Tiber. The walls encircled the basilica, nearby churches, convents and hospices, as well as the local neighborhoods. The pope consecrated the small town in 877, shortly after the Pope’s sea battle victory over the Muslim fleet at Cape Circeo, and it proved to be more than a match for the continuing depredations of the Saracen marauders. The Pope also built an almost two-thousand-yard-long portico from the Porta Ostiensis to the basilica, with over a thousand columns and a roof made with lead. All traces of the walls of Johannipolis and the portico to the city gate have regrettably disappeared.

The Protestants and Spaniards also sacked the Apostle’s tomb in the Bourbon Sack of 1527. Most probably the monks took steps to protect the relics, and the treasures in the city were the more likely target for these merciless mercenaries.

|  | |

In the night of July 15-16, 1823 the grand old basilica which had survived for 1400 years burnt to the ground, a victim of the negligence of two workmen who had been repairing gutters on the roof and who carelessly let their embers fall onto the roof. Fortunately, the transept and Arnolfo’s baldacchino, the Apostle’s tomb beneath it, and the cloister survived. Everything else was burned or melted.

The Church was rebuilt along the lines of the ancient basilica, but it is a cold and foreboding replica. Saint Paul’s was a basilica that simply could not be replaced. The new Basilica, finished in 1854, preserves the plan and proportions, and large parts of the exterior walls of the Theodosian basilica, but in the words of the nineteenth century Christian art authority Anna Jameson: “I saw this church a few months before it was consumed by fire in 1823; I saw it again in 1847, when the restoration was far advanced. Its cold magnificence, compared with the impressions left by the former structure…rich and venerable…saddened and chilled me.”

|  | Areial photo Pontificia Amministrazione | |

And now we begin our visit. We first pass through the square and the palm-treed quadro-portico. Here we find magnificent columns-- red Baveno granite monoliths in front of the basilica (be sure to notice the head of Saint Paul in each of these capitals) and Montofarno granite on the other three sides. The façade has an unremarkable modern mosaic with Jesus, Peter and Paul, the Lamb of God with the Rivers of Paradise, and the Twelve Sheep (Apostles) and the cities of Bethlehem and Jerusalem, all taken from the theme begun at Cosmas and Damian. The four Prophets Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and Daniel are between the windows.

We must mention here that the façade was graced in the early fourteenth century with a mosaic by Pietro Cavallini (1259-1330), my favorite artist. Remnants of what was left after the 1823 fire are on the inside of the Triumphal arch, toward the tribune, but they are, in Roman art historian Walter Oakeshott’s words, “a ponderous travesty of the original.” This “Cavallini” has Mary and Child, the Baptist, John XXII (1316-1334), and Matthew and John.

|  | The very front of Saint Paul's--what you see as you approach the basilica. | The court is dominated of course by the foreboding statue of Paul with his sword and epistles. Paul was given the sword because as a Roman citizen he was privileged to die by the sword, but perhaps because he wielded the Sword of the Spirit, or perhaps for his persecution of the Christians. Medieval knights regarded him as their patron saint because of his sword (some even believed that he had been a soldier). Knights had the custom of rising if the Epistle was from Paul’s letters. John Chrysostom owned a portrait of Paul: he was a man of short stature, with a lofty forehead and an aquiline nose, bright eyes, a mouth showing firmness of chamber, with a long, flowing, pointed brown beard. Not the stern and frightening gentleman we find here! |  | |

We enter through the Holy Jubilee Door and turning around we encounter on the right the bronze Byzantine door of the Amalfian Consul Pantaleone made for Hildebrand, Abbot here, to become Gregory VII (1073-1085). The doors were made by Staurakios of Chios in 1070. There are fifty-four divisions, or twenty-seven panels, decorated in silver, enamel, and niello inlay, with scenes from the Old and New Testament. All the subjects are in the Byzantine, thin, lifeless style, the inscriptions in Greek. The figures are outlined in silver and the faces brightened with colored enamel.

The inscription over the Holy Jubilee Door celebrates the 1967 restoration of the doors, which had been severely damaged in the 1823 fire, under Paul VI (1963-1978). Over the entrance are six fabulous columns of Oriental alabaster, donated by Egypt for the new Basilica.

|  | |

We now enter the cold, immense, and empty nave. Here we have eighty monoliths of Montofarno granite. The base, shaft, and capital are all one piece of stone! Above are the mosaic clypei of the popes, from Peter to Francis.

Once here on the walls of the nave were the glorious frescoes of Pietro Cavallini. These were extensive paintings of the Lives of Peter and Paul, worked within the remnants of the earliest frescoes that dated to the time of Theodosius and Galla Placidia. On the opposite wall Cavallini frescoed scenes from the Old Testament. Professor John White tells us based upon surviving drawings that these were “electrifying” with a new “narrative realism” that reflected “ambition and achievement.”

The ceiling has the coat of arms of Pio Nio, Pius IX (1846-1878), who reigned during the completion of the new Basilica. Look to the side aisles where in the niches we find the twelve Apostles.

|  | |

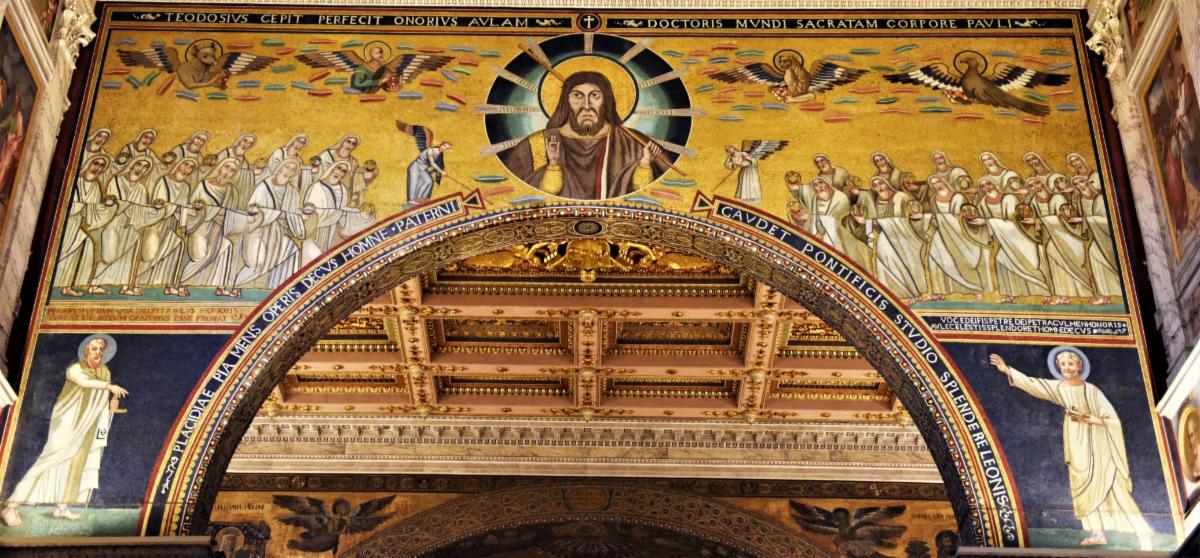

On our way to Paul’s tomb we see the Triumphal Arch of Theodosius, completed and repaired by his dare-devil daughter Galla Placidia(386-450)(daughter of the Emperor, prisoner then wife of a Gothic King, then wife of a Roman General, and finally Mother/Regent to the Roman Emperor) and Pope Saint Leo the Great (440-461).

The Roman Triumphal Arch was taken up by the Christians to celebrate the victory of Jesus. The mosaic of the arch was put up during the original construction of the Theodosian basilica but was repaired/redone by Leo after the lightning fire of 440. The mosaic was restored more than once before the fire of 1823, and then again after that fire, none of the work admirable or even barely adequate.

The subject is from Revelation—the Adoration of the Twenty-four Elders presenting their jeweled crowns, the four beasts of the Apocalypse above. Jesus in an aureole is awkwardly done, with too small hands that are twisted out of position. His head is unpleasant, his gaze off. He wears the Byzantine Toga Praetexta, reflecting the influence from Ravenna, a Greek city even though the seat of the Western Empire. Paul is on the left, Peter on the right.

The inscriptions are perhaps the most special feature of the arch mosaic. On the left, at the top of the mosaic we find: TEODOSIVS COEPIT PERFECIT HONORIVS AVLAM (Theodosius began and Honorius (his son) finished this Aula (church). The counterpart on the right: DOCTORIS MVUNDI SACRATAM COPORE PAVLI (The sacred body of Paul one of the doctors of the church is here).

On the rim of the arch: PLACIDIAE PIA MENS OPERIS DECVS HOMNE PATERNI GAVDET PONTIFICIS STVDIO SPLENDERE LEONIS (Placidia’s pious soul congratulates Leo on his zeal in successfully finishing the decoration of the paternal work).

The inscription for Paul reads PERSEQVITER DVM VASA DEI FIT (PAVLVS ET IPSE) VAS (FI)DEI ELECTVM GENTIBVS ET POPVLIS (Paul persecuting the elect of God, himself became a chosen vessel to show light unto the Gentiles and nations).

Peter’s inscription reads IANITOR HIC COELI EST FIDEI PETRA CVLMEN HONORIS SEDIS APOSTOLICAE RECTOR ET OMNE DECVS (Peter is the Gatekeeper of the Kingdom, the rock appointed by God, the ornament of heaven).

There are also marble inscriptions that record the repairs of 1826, which involved taking the mosaic down and supposedly restoring it in accordance with the original, and yet another restoration in 1853. Walter Oakeshott says that “the present mosaic is a travesty of the original” and that its early character is “almost unrecognizable.”

|  | We now enter the Confession for the Apostle (Timothy-in the porphyry mensa- and Titus’ relics are also here), which we have described above. The marble sarcophagus was uncovered in 2006, and in 2009 Benedict XVI announced the discovery of bone fragments in the sarcophagus carbon dated to the time of Paul, which he declared to be the relics of Paul. Hopefully the iron grating will be open for you to see the sarcophagus. The legendary chains that bound Paul at the Mammertine are above. |  | Above the Confession is unquestionably the most precious possession of the church, save for the tomb of the Apostle. This is the baldacchino of Arnolfo di Cambio, made in 1285. Here Arnolfo, student of Nicola Pisano the Renaissance Father of Sculpture, combined the Gothic and the Roman Classical and the Cosmati mosaic. Professor White tells us that this is “the supreme surviving example…. (of) the fusion of the Roman Cosmatesque and Northern Gothic traditions.” ”Gothic forms …harmonize with the smooth Roman classicism…” |  | |

The columns of the baldacchino are Roman rosso antico, while the capitals, pinnacles and gables are pure French Gothic. The jewels of the canopy are the statues in the corner niches, and the relief sculptures in the pendentives, and the flying bat angels underneath the canopy, all surrounded by beautiful Cosmati mosaic work.

The facing section has trefoil ogival arches with triangular typana above. On the left is Paul with his sword, his head a bit oversized in the Arnolfo fashion, with a kindly countenance, and a look of bewilderment (“what am I doing up here?”). Arnolfo has given Paul and the other subjects real life classical Roman clothing with magnificent folds. Paul is life-like, full bodied, and human, giving us real emotion and casting off the Byzantine stare. On the other side we have Peter, with a full head of curly hair, a curly beard, his ears flayed out, his keys in hand.

|  |  |  | |

In the gable we have the sparkling geometric Cosmati mosaic, and in the middle a rosette wheel window held by two angels with wings of gold, each balanced by a foot in the air, a long arm extended to hold the gilded window. The angelic drapery is superb. The angels, certainly Roman victories, look straight at us.

The inscription tells us that in 1285 Arnolfo made the canopy with his friend Petro for the Abbot Batholomew. In the pendentive below we have the Abbot (1282-1297) giving a model of the ciborium to Paul, who is in the left pendentive ready to receive the model.

Luke (convert of Paul)(who lost his hand, perhaps in the fire of 1823) and Benedict are in the other two corner niches. Some say Timothy is here, not Luke.

| Abel presenting a sacrifice. The Hand of God blessing it? | |

The other pendentives are equally and thoroughly enjoyable, with Adam and Eve before the fall, and tempted by the devil with his apple. God seems to be warning Adam of the consequences (using a form of the comput digitalis to make his point). Cain and Abel are here too, with offerings. Prophets round out the series.

My favorite figure is the hanging angel thurifer undeath the canopy. The foreshortening is brilliant—a lost art since the time of the Empire, of no value to the two dimensional Byzantine. We also have stags, peacocks, pelicans, unicorns, sea lions, eagles, and lambs—white on a dark background with strings of coral encircling them. The birds and fish are done in mosaic within the clypeus (probably made by Arnolfo’s associate Petro). Note that the four ribs end in a grand rose with twisted leaves, and a golden calyx, all this brilliant intaglio work.

|  |  |  | Next we turn to the Paschal Candlestick, made 1180 by the Cosmati Nicolas di Angelo and Pietro Vassallettus. The Paschal Candlestick came into the Easter Vigil in the tenth century, placed near the altar. This one is signed by the Cosmati. We can see here that the amateur of the medieval period has not yet left us, with the oversized and dominant heads, the lack of depth, seeming child’s work. The candlestick somehow survived the fire of 1823. Follow the scenes—the Crucifixion, the condemning Sanhedrin, Christ before Caiphas, the Derision, Christ before Pilate, Pilate washing his hands, and the Ascension. |  |  | |

From the candlestick we go to the apse mosaic. The current state of the mosaic is unfortunately a tragedy. It was made under Honorius III (1216-1227), who in 1218 successfully besought the Doge of Venice to send him mosaicists from Constantinople (which the Venetians and the other Crusaders had conquered in 1204). The mosaic has been hopelessly repaired and restored (it was taken down after the fire but had been disastrously repaired even before that), and thus Professor Oakeshott tells us that “the old mosaic was almost entirely destroyed.” Four heads were removed from the apse mosaic before it was “restored,” and three of these are in the sacristy—Peter, James and John.

The apse mosaic has an enthroned Jesus with Paul, Luke, Peter, and Andrew. Honorius kneels at Jesus’ feet. The vacant eastern Hetimasia is below, with the implements of the Passion, the Twelve Apostles, and Mathias, Barnabas and Mark. The small figures in the mosaic are perhaps their most interesting aspect: Pope Honorius kneels before Jesus,and below the Hetismasia are the five Holy Innocents and Arnolfo the Sacristan and Giovanni Caetani the Abbot! These are in the small zone we think still holds original ancient tesserae.

|  | The Chapel to the left of the apse designed by Carlo Maderno (1556-1629) has a Crucifix attributed (most likely in error) to Cavallini and Tino de Camaino (1280-1337). It is said that this Crucified Jesus spoke to Bridget of Sweden (1303-1373). The kneeling Bridget in the niche left of the entrance is by Stefano Maderno (1576-1636). | And now we move to the Cloister off the right transept, another treasure of this church, also the work of the Cosmati. San Paolo and the Lateran have the two most beautiful cloisters in Rome, the Lateran the best. The arcaded quadroporticus with twinned double columns and the cornice with exquisite Cosmati geometric multi-colored mosaic and loaded with human and lion heads is very special indeed. |  | |

The setting is peaceful, a rose garden, and there are few visitors to disturb us as we admire the Cosmati archivolt populated with six pointed stars and hourglasses, and the intertwined guilloches and mixed braids. The columns are “fluted, geminated, ophidian, wreathed, and turned.” Paoloma Pajares-Ayuela. The spandrels have small sculptures and bas-reliefs of grotesques and birds, dogs, Adam and Eve and the Tree of Knowledge, and multiple kinds of masks. Some of the tesserae are marble of white, red, yellow and green, some glazed of white, red, blue, black, and gold. The artists used porphyry and verde antico throughout their work.

The cloister was begun by the Cosmati Vassallettus and his son Petrus (who also made the Paschal Candlestick) in 1205 under the Abbot Peter of Capua (1193-1209) who began with the north-east side. The work was suspended until 1225 (perhaps for the apse mosaic), and the other three sides were finished in 1235. Look closely and you will see the difference in the sides. The inscription here recites the name of the Abbot --CAPVA PETRVUS.

|  |  | We end with a visit to the anteroom to the sacristy where we find the heads removed from the apse mosaic. Mr. Oakeshott doesn’t like them but I find them quite beautiful! Though Byzantine, Peter has left me with a lasting impression. | Now it is on to the place of the Apostle’s martyrdom, Tre Fontane. You take the bus on the south side of the Basilica to get to the shrine. Paul was led out of the city (legend has it that he was imprisoned with Peter in the Mammertine dungeon off the Forum) to the Aquae Salviae on the Via Laurentina. He was accorded death by the sword as a Roman citizen, and the legend is that his head bounced three times, and at each location a fountain sprung up, hence Tre Fontane. | The Tre Fontane church above the legendary place of Paul's execution with the miraculous fountains | |

There are three churchs here, the Church of Saint Paul of the Three Fountains, Santa Maria Scala Coeli built over the relics of Saint Zeno martyred under Diocletian in 299, and the church and monastery of Saints Vincent and Anastasius, now home to the Trappists. The modern baroque Fontane Church was designed 1599 by Giacomo della Porta (1532-1602), the statues atop the cornice are by Nicolas Cordier (1567-1612). The Maria Scala Coeli is also by della Porta. The Church commemorates the legend of a ladder to heaven provided by the Virgin to the 10,000 slaves who made the Baths for Diocletian and were subsequently martyred with Zeno and buried in the catacombs here. Vincent (martyred 304) and Anastasius (martyred 628 in Persia, translated to the Tre Fontane) have the humblest of the three churches, which is home to the Trappist cell.

You can buy the beer of the monks here (quite strong). Because of its location, there are few visitors to bother you as you enjoy your repaste.

| |

Vincent and Anastasius, Maria Scala Coeli to the right | |

|

Our next walk takes us to the neighborhood of San Giovanni in Laterano, the Baptistery, and the Scala Santa. Here we will see Francesco Borromini's architectural masterpiece, and certainly the best Cloister in the world, and then visit the first Christian Baptistery, and then if your knees are strong enough we will "knee" up the legendary stairs Jesus used at Pontius Pilate's Palace.

Copyright 2023 all rights reserved Greg Pulles

| | | | |