A Walk up the Clivus Scauri to the Parco Celimontana | |

The Cosmati Mosaic of the Slaves Freed by the Trinitarians, San Tomasso in Formis |

|

|

Today’s walk takes us from the valley of the Palatine up the ancient Clivus Scauri to the top of the Caelian hill and the spacious park of the Villa Celimontana. In ancient times the Caelian hill was bathed in a forest of pines, oaks and cypresses and even an occasional palm, and was known as the Mons Querquetulanus or the “Hill of Oaks,” the sacred wood of the Camenae, the goddesses of wells and fountains. The Vestal Virgins came here daily to draw their water from the spring in the grove. The name “Caelian” comes from Coelius Vibenna, an Etruscan Lucomo (king) of Ardea who came to the aid of Romulus in his war against the Sabine King Tatius, and who thereafter took up his abode here. But some say Vibenna with the Tuscan Servius Tullius conquered the Caelian hill and then all of Rome, enabling Tullius to become the sixth King of Rome.

For centuries the entire area was taken up by monks of the Camaldolese, Passionist, and Redemptorist Orders, and by the Augustinian nuns of the Quattro Coronati. They raised their considerable gardens over and amid the ruins of ancient temples and palaces, which in Renaissance and Baroque times were cruelly robbed of their marble for the Lateran restorers.

| |

A proper walk here starts with the large black bust of Mother Teresa, a donation of the Indian people, which sits at the base of the hill. Her nuns have a homeless shelter, convent and chapel on the right side of the Gregorio Magno. | |

The beautiful travertine facade of Gregorio Magno. The atrium hides behind, the church further back. The architect was G.B.Soria, who restored the church for Cardinal Borghese, the Cardinal's emblem of dragon and eagle above the portals. | |

|

Gregory the Great (590-603) received his title because almost single-handedly he saved the people of Rome from the abyss into which the Eastern Empire had abandoned them, and protected them from the Lombards who from c560 continously menaced the city from the north. He is one of the Four Fathers of the Latin Church with Augustine, Ambrose and Jerome. Gregory established the papacy as the only real civil power in the city after the Byzantines had abandoned it to its fate, and contributed his family’s considerable wealth, which was based on the Caelian, to the well-being of the people.

Gregory converted to monastic life in 574 and set up a monastery to St. Andrew on the family’s palatial grounds on the Caelian, and also six others on the family’s estates in Sicily. In 579 Pope Pelagius II (579-590) plucked him from monastic life and made him apocrisarius (legate) to Constantinople where he distinquished himself at the court of Maurice to the point that he was selected as Godfather to Maurice’s son.

He returned to Rome in 585 and was promptly appointed deacon, which in those times meant round the clock service to the church’s temporal needs. He was unwillingly elected pope in 590 after the death of Pelagius, who had succumbed to the plague then terrorizing the city (the people had to find Gregory in the woods outside the city where he had taken refuge from the election). As pope his first act was to lead penitential processions to Maria Maggiore. When they passed Hadrian’s great tomb fortress, Gregory had a vision of the Archangel Michael sheathing his sword into its scabbard, signaling the end of the plague, a scene made permanent with the statue added thereafter to the summit of what was forever after the Castel Sant’Angelo. Gregory is also responsible for the conversion of England; one day he encountered three English lads in the slave market and remarked “Non Angli, sed Angeli” or “Angels, not English.” He promptly sent Saint Augustine of Canterbury as missionary to England.

Gregory’s church on the Caelian (which the Church has not favored with the designation of Basilica!) in no wise approaches the remarkability of the man. The church has been hopelessly baroqued, and has only its floor, the chapel of Gregory, and the travertine façade to commend it.

After Gregory’s monastery declined in the troubled seventh century, which saw the rise of Mohammed and his holy war on the Christians, Gregory II (715-731) came to the rescue and rebuilt the church c 715. The church then slipped into obscurity until the sixteenth century, when Gregory XIII Boncampagni (1572-1585) gave the church to the Camoldolese, who began restorations. In 1633 Cardinal Scipione Borghese entered as patron, emblazoning the church with the family dragon. Giovanni Battista Soria (1581-1651) was the restorer, and if we do not admire the baroque inside, we do admire the false façade outside, a travertine beauty. Soria recognized that travertine was best seen in its simple natural state, in its solid mass, a principle he employed with great success at Santa Maria della Vittoria. Travertine with its deep and thorough crevices really is best left alone to achieve its own effect. Michelangelo and Bernini were to learn this lesson for the palaces on the Capitoline and the colonnade at Saint Peter’s.

|  | |

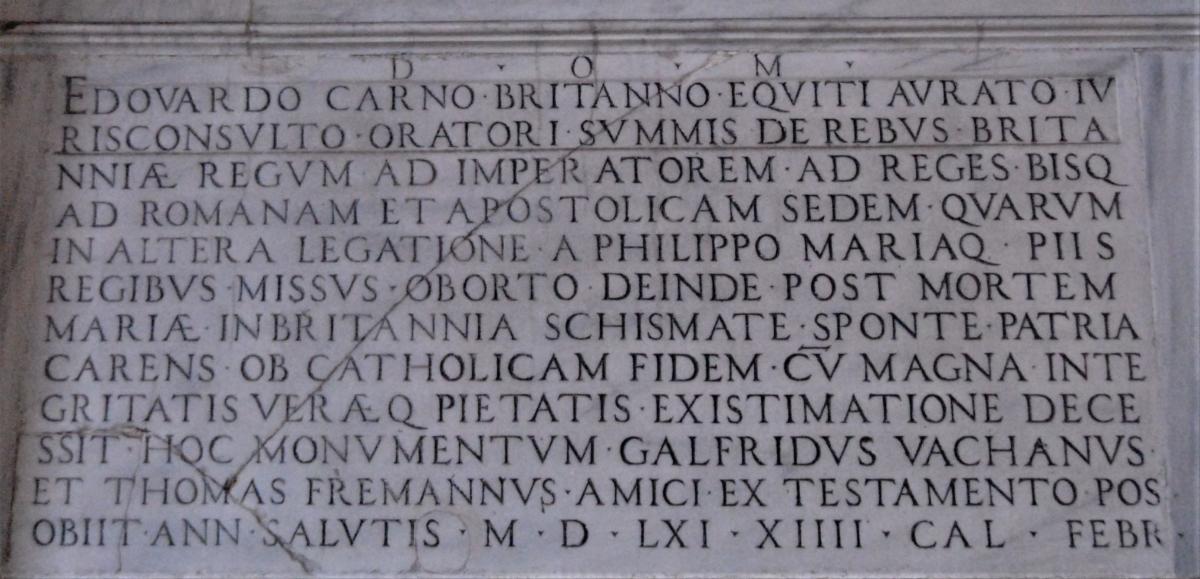

As we pass through the façade into the atrium (which occupies the site of the ancient parvis), we should pay attention to the tombs here. On the left we have Sir Edward Carne (d1561), sent to Europe and Rome by Henry VIII as a member of the Commission trying to obtain an annulment of Henry’s marriage to Catherine of Aragon. Subsequently made envoy to the papal court, he became as a loyal Catholic a favorite of Paul IV Caraffa (1555-1559) who induced him to stay in Rome as the warden of the English hospice after the hostile Queen Elizabeth suppressed the Roman embassy. The first line of the inscription on his tomb recites that he is a Briton and a Knight of the Golden Spur. Note in the middle of the inscription the reference to the schism in Britain after the death of Queen Mary and Carne's voluntary exile from England on account of his Catholic faith.

On the right in the atrium is the tomb of the Bonsi brothers, Antonio and Michele. The work by the Renaissance sculptor Luigi Capponi (1450-c1506) was unique, solving the problem of not enough room for two sarcophagi by placing busts of the deceased in niches. The portraiture, now marred by vandals who have knocked the noses off, is of excellent quality, and the relief above of the Madonna and Child is also well regarded.

|  |  | Lastly in the atrium is the tomb of the courtesan Imperia (d1511), the mistress of the wealthy Sienese banker Agostino Chigi, which is directly opposite the Bonsi tomb. She was the delight of Rome; beautiful, musical and literary. She died at the young age of twenty-six, and was afforded the funeral of a princess, and a prominent tomb here at Gregorio. She loved flowers and her tomb is full of them. The forgiving Madonna and angels are here too. What is missing is Imperia’s name, which was taken off, the name of the Canon Lelio Guidiccioni substituted! | The uninspiring baroque nave | But amidst the oppressive baroque we find an amazing combination of Cosmati guilloches and quincunxes | Now we enter the church, sometimes through the front door, sometimes from the right aisle. On my first two visits the locked front outer door was hanging from the hinges, a sign of lean times. Sometimes you need to ring the bell on the monastery door on the right to be let in. As we enter, we are overwhelmed by the last eighteenth century baroque redo, but we look past it to the splendid restored Cosmati floor, surely a contestant for the highest honor in the city. | We go to the end of the right aisle, where we are greeted by a very beautiful chapel for the saint. Here we see the altarpiece by the undistinquished Bolognese Sisto Baldalochi (1585-c1619/1647) with Gregory’s emblem of the dove speaking into his ear. When Gregory was dictating his homily on the prophet Ezekiel, his scribe, working on the other side of a veil separating them, was concerned over a long lapse of time and Gregory’s failure to respond. He pulled the veil back a bit, surprised to see a dove who had his beak between the lips of the saint. When the dove pulled his beak out, Gregory began again to dictate his homily. Apparently it was not felt appropriate to have the dove talking into Gregory’s lips, and so we will see the dove always positioned with his beak into the pope’s ear. |  |  | |

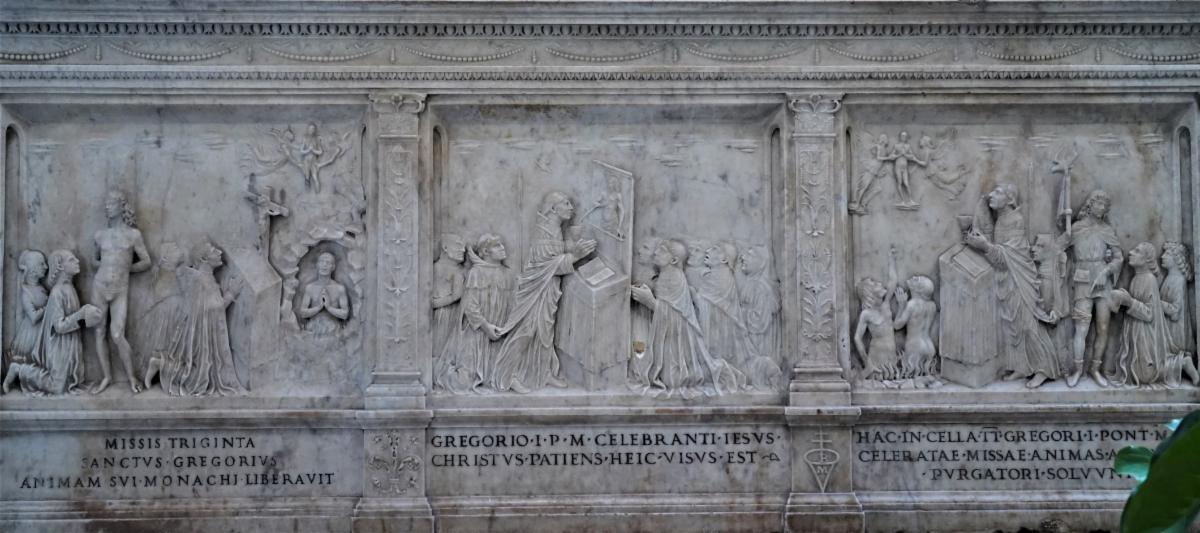

The predella of the altar has three of the charming stories of Gregory, carved either by Capponi or Mino de Fiesole (1429-1484). In one scene, Gregory prays for the soul of Trajan, whom he regarded as a good man. Gregory was moved by Trajan’s justice: a woman had the tenacity to stop the Emperor on his horse and beg for justice for her son, who had been murdered. Trajan said he would look into it on his return from campaign. The woman persisted, what if the Emperor was killed in battle? Trajan was moved by the woman’s bravery to investigate and delayed his departure to secure justice for the woman and her slain son. Gregory prayed for the Emperor’s soul, and we see on the predella that soul raised from the fires of purgatory. It was Gregory who developed the Catholic notion of purgatory as the intermediate place where the sinful could be cleansed of their sins.

In the other two reliefs we have Gregory exposing the consecrated host to a disbelieving woman, from which the Savior’s blood flows, convincing her of the Transubstantiation, and then the souls in purgatory being cleansed and released into heaven.

| The real treasure in the chapel is Gregory’s Cathedra, or bishop’s chair. This really may be the chair Gregory used. They won’t let you anymore, but my daughter Mel and I were able to actually sit in the chair, and touch the arms with their worn-off animals’ heads. The swirls on the back mark the still prevalent Roman vine-scroll. The chair now sits on a platform of Cosmati work (wasn't there at our sitting). | Gregory's tiny cell. How did he possibly spend every night in here? | |

On the left of the tribune is the Salviati Chapel, with a painting of the Virgin, the legend is that Gregory spoke with Mary whilst kneeling in prayer before it. The chapel was made by Carlo Maderno (1556-1629) and Francesco Volterra (1530-1594).

From the Magno, we go to a far more beautiful place, the three chapels that are to the north of the church, usually only open on Saturdays, but well worth the timing of your visit. On the left we have the Chapel of Barbara, in the middle Andrew, on the right Gregory’s mother Sylvia. It is said that Gregory founded these chapels, but we think it is the good Venerable Cardinal Baronius (1538-1607) from Nereo ed Achilleo whom we should thank for his work here in 1600.

|  |  | |

In the Chapel of Barbara we find Nicolas Cordier’s (1567-1612) statue of Gregory, with the usual Gregorian Dove of the Holy Spirit. The face of Gregory is extremely detailed, the artist is said to have based it on an ancient painting of the saint. In front of Gregory is the table at which Gregory fed twelve hungry Romans every evening, a story repeated in the wall fresco. Gregory, who called himself Servus Servorum Dei, or servant of the servants of God, is perhaps more responsible than any other church leader for the “preferential option for the poor” by which the Church guides itself.

Gregory gave alms on successive days to a poor shipwrecked sailor, and when the man returned a third time, Gregory found himself without money, and so he gave the man the silver basin which his mother had bequeathed him. At one of the evening meals held round the table we now see, Gregory noticed there were thirteen pilgrims. When Gregory asked his steward, he was politely told there were only twelve as he had ordered. As Gregory looked at the man, his countenance kept changing--first he was old, then young, a man, then a woman. He was moved to pull the visitor aside and ask who he was. The pilgrim replied: “I am Wonderful, the beggar sailor whom thou didst relieve and to whom you gave your last possession.” This story led to the papal practice of the pope serving thirteen of the poor on Maundy Thursday here (the last dinner served in 1870, the year the Italians threw the pope out as master of Rome).

The wall frescoes by Antonio Viviani (1560-1620)(called the Urbino mute) also tell the story of Gregory’s encounter with the English boy slaves that he ransomed in the Roman Forum.

|  | In the Chapel of Andrew we encounter the great 1609 Baroque duel between Guido Reni (1575-1642) and Domenico Zampieri-- “Domenichino” (1581-1641), who were commissioned to paint opposing frescoes of the martyrdom of Andrew. Domenichino is on the right. When his teacher Annibale Carraci came to visit him during the painting, he found Domenichino worked into a rage as he was painting one of the executioners. “Bravo!” yelled Caracci, who exclaimed as he embraced his pupil “Today it is I who am taking a lesson from you.” Reni’s work on the left has Andrew in ecstasy beholding his cross. Both Reni and Domenichino painted their own portraits into the lower left of their works. See if you can find them! This is truly a special place—where else can you find such a competition between two of Rome’s masters with such massive frescoes opposing each other in a small chapel, where are free to approach as closely as we wish? |  |  |  | Finally, we visit Sylvia’s Chapel. Here Cordier has given us another statue, this time of Gregory’s mother. Above Sylvia is the famous Angelic Concert, also by Reni. Though Roger Thynne says: “it belongs to an age where sentiment was not considered bad form, and before it occurred to people to label every emotion ‘cheap,’” it is a favorite for me as the angels seeming to be looking down and playing all these wonderful instruments just for me. | The Concert of the Angels by Guido Reni. God the Father above is for me the most pleasing representation of Him in Rome. The three little angels singing from their sheet music is also special. The trombone is my favorite instrument, but there are ten from you to choose from! | |

The three chapels are a special place indeed. Visit if you can, you will not regret your peaceful time here under the Roman cypresses, looking out at the Palatine across the way, and taking in some of Rome’s best and most underseen works of art.

Now we go down the steps from Gregorio, thank Gregory for his work for the Jews (he worked diligently to protect them from forced conversion) and the slaves, both white and black, whom he tried to help with his preaching against the institution of slavery, then wave at Mother Teresa, and begin our ascent of the Clivus Scauri. If you have time, there is a little museum nearby here to the north, called the Magazino al Celio, or the Caelian Antiquarium, which has a collection of items of everyday Roman life, as odd as the remains of a water conduit, inscripted waterpipes, and ex-votos in terra cotta.

We now formally begin our walk on the stones of the two thousand one hundred year old Clivus Scauri.

|  | The apse of Giovanni e Paolo high above the Clivus Scauri |  |  |  | |

“Clivus”means ascending walkway, while “Scauri” probably comes from Marcus Aurelius Scaurus, a Roman general defeated and captured by the Cimbri in Gaul and revered for his defiance and acceptance of death over capitulation. It is a special road in that it retains the appearance of the ancient roads of Rome with its stone pavement, and the brick walls on both sides, and the buttresses that span it. The last of these may date to the third century, the rest added in the twelfth century to buttress the walls of SS Giovanni e Paolo.

As we ascend we see on the left the door to the ancient Roman Casa that lies beneath the basilica. The legend of Giovanni and Paolo is that they were two high officers at the court of Constantina, a daughter of Constantine, who lived in their palace here on the Caelian. They may have been brothers. They refused the mandate of the apostate Emperor Julian (361-363) to honor the pagan gods and were beheaded in 362 for it, being buried in the walls of their home: “our lives are at the disposal of the Emperor, but our souls and our faith belong to God.” Julian's soldiers secretly buried the martyrs in their own home to avoid an uprising in the Christian community.

Pammachius was the son of Byzantis, a wealthy Roman senator, and also a friend of St. Jerome. Byzantis had begun a basilica over the tomb of Giovanni e Paolo. Pammachius finished the church after the death of his father, and it was called the Titulus Pammachii in keeping with the early Christian tradition of naming the church for the donor. In 535 the name was changed to SS Iohannis et Pauli.

The Church we see today makes use of Pammachius' original building. We can see high on the facade five large walled-in openings with their classical columns, and another five at the ground level, with two surviving supporting columns, all from the original church. Pammachius's church had a steep staircase leading down to the graves of the martyrs, making this a basilica ad corpora.

The Goths did substantial damage in the their sack of 410, and we should be able to see gashes and breakage in the columns high on the facade, though I can't make this out. At some point windows were substituted, leading to the unpleasant attic we see today. Further restorations occured in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, some of it due to the fires of the Normans in 1084.

|  | A notice posted next to the entrance to the Casa on the Clivus Scauri | The twelfth century Campanile is the only one in Rome completely detached from its parent church; it sits atop the travertine base of the Temple of Claudius. The "polychrome cermaic plates and porphyry and serpentine marble panels" and the double arched windows, each with a small white marble column, resting below an intricate dentiled cornice, make this one of Rome's best. Joseph N. Tylenda | |

The Roman house is the only surviving example of an early Christian dwelling house, showing us how the Romans of their time lived and arranged their homes. The entrance that was once through stairs on the far end of the right aisle of the church is no longer available to us, and we need to buy a ticket at the entrance on the Clivus Scauri. I bought the ticket and for me it was worth it. Leo XIII (1878-1903) put up an altar at the site of the saints’ martyrdom, together with a fenestella confessionis through which the pilgrims were able to lower their brandea to touch the relics of the saints. There are numerous Christian frescoes to interest us here, very much like those in the catacombs, and these include Moses and the Burning Bush, a woman praying in Orante, and the Apostles, and the Martyrs. The best preserved fresco is a pagan one, in the nymphaeum, which gives us Persephone's return from Hades. The triclinium has second or third century frescoes of young men with festoons, surrounded by all sorts of animals and the usual vine tendril in the vault.

The piazza in front of the Basilica gives us a pleasant view of the façade of the church and its campanile on the right, which sits atop the remains of the ancient platform of the Temple of the Deified Claudius, the only part of that great temple which survives. The campanile is quite unique with its serpentine and porphyry discs and plates and its elaborate cornices and dwarf columns. It is perhaps the most beautiful in its arrangement, rivaling the one at the Maggiore.

|  |  | The Cosmati eagle clutching a lamb over the portal. Perhaps one of my priest readers can elucidate. | The portal is surrounded by a narrow strip of Cosmati mosaic, and two Cosmati lions guard the entrance. These lions frequently have a baby in their paws, a symbolism we can't explain. | |

The angled brick façade with its portico is pleasing, but it was more so before the rectangular windows replaced the Roman arches we see in the brick. After the Norman fire of 1084 the mostly destroyed church was rebuilt by Cardinal Giovanni Conti of Sutri in the twelfth century. The vestibule and campanile date to this time, and we see the Cosmati work in the mosaic pavement and the lions guarding the door. You can see the inscription for Giovanni di Sutri near the entry.

The nave is not beautiful, and we might even describe it as garish. It is usually feted for a wedding, which is the primary source of income for far too many of the churches of Rome. There is a little fence around the tomb of the saints, who for centuries resided far below us in the ancient house (actually a little to the right of this, marked by the glass disc). They were brought up to the main altar in the sixteenth century. The Cosmati floor is a refreshing respite from the overwhelming baroque here. Cosma, grandson of the founder of the Cosmati family, is the artist. He also did the Cosmati of the original altar, now hidden. The granite columns were probably donations of Pammachius.

|  |  | |

The embalmed body of Paul of the Cross (d 1776, feast day April 28), founder of the Passionists who preside here and in their adjacent monastery, is beneath the altar left of the tribune area. The saint also has a chapel on the right side of the nave encased with precious alabaster and seme-santa marble, the great alabaster pillars the gift of Pius IX in 1868.

We now make our way to the Parco Celimontana which is on the south side of the Clivus. We can stop to see the Gate to what was once a small Borghese garden planted here by Cardinal Scipione Borghese, emblazoned with the dragon, with a faded fresco of Gregory and his dove over the portal. The library of Pope Agapito inherited and expanded by Gregory was (still is?) perhaps within this gate.

The entry to the park is now open: for decades you couldn’t enter off the Clivus and had to enter on the east side of the park. We are welcomed by the lofty pines of Rome, shading a very large and largely unused park. Certainly there are only locals here, and you should consider a picnic lunch, or at least wine and cheese, as you soak in the quiet and the view of the Caracalla on the south.

This park and what was formerly the Villa Celimontana were built in 1580 for the wealthy family of Giacomo Mattei by Michelangelo’s student Giacomo del Duca (1520-1604). The property went through many owners, the last of these the Bavarians. The state confiscated the Villa in World War I and in 1926 gave it to the Societa Geografica Italiana, which still resides here in the greatly neglected building.

|  |  |  |  | |

Low and behold the park owns three of the rare and spectacular Mussolini era 24/7 "prism" drinking water faucets with the bronze she-wolf! Practice your water faucet skills--plug the hole with your finger.

Finally, we visit on the far east end one of Rome’s Egyptian Obelisks. This was one of four erected in Egypt by Ramses II between 1486 and 1420 BC, taken to Rome by Augustus. The little ball on top is unique in Rome’s collection. Ramses’ name is in the inscription. Can’t get enough of of the Egyptian obelisks!

| The American Legion is still proud of Christopher Columbus and the other Italian explorers, or at least it was in 1947 when they put up this plaque on the Villa! | |

We now exit back onto the Clivus—it now becomes the San Paolo dei Crucifici. Down the road on the north side you should try to take a peek into the gardens of the Passionist Congregation. Here you will find an old fashioned "orto" "with lavender hedges and oleanders surrounding plots of tomatoes and lettuce." Georgina Masson. These once were part of a nymphaem of the gigantic gardens of Nero's Domus Aurea. This is the largest private garden in Rome. It affords over the steep side of the Caelian a spectacular view of the Colosseo. Think of the distance-- the center of Nero's house was north of what is now the Colosseo! There is a ginormous rectangular terrace (175 x 205m) built by Vespasian in the early 70's which sits at a level "on a par with the top of the Palatine" (Amanda Claridge) that still dominates the garden of the Passionists. There is also here the tunneling for the Vivarium that housed the wild beasts used for the games at the Colosseo. My friend Father Johnson says the tunnels are now home to "the wild cats of the Caelian."

We see from a distance the Arch of Dolabella, the entrance to the ancient Servian Republican wall made by the Consuls P. Cornelius Dolabella and c. Junius Silanus in 10A.D., also called the Porta Celimontana. The travertine arch of Dolabella was never decorated, there is a plaque on the attic of the external façade which records the making by Dolabella and Silanus. In 211 Caracalla used the arches for the Neronian aqueduct, which was a second branch of the Aqua Claudia. There is a small room behind the window we see which Saint John of Matha used as the nucleus of his tiny hermitage from 1209 until his death in 1213.

|  | The travertine Arch of Dolabella--the Caelian Gate. The street level has risen from accumulated dirt some 2 metres, resulting in the "squat proportions." Amanda Claridge. The superstructure of Nero's aqueduct "steps across (the arch) in a dog-leg." The aqueduct continued to the east, bringing water to the Palatine. Saint Tomasso had his little room behind the window. | The Cross of the Trinitarians that was in the portal was missing on my last trip in October!? | The tiny papal insignia over the portal to Tomasso | |

Next to the arch is the present entry to the small and wonderful church of Tomasso in Formis. The French theologian Giovanni de Matha saw a vision of an angel in white when he elevated the host in his first mass as a priest. The angel had a red and blue cross on his breast, with his hands in benediction on the heads of two slaves, one a white European the other a black Moor. The Bishop of Paris sent de Matha to Rome to tell Pope Innocent III (1198-1216) of his vision.

The Pope as it happened had the same dream, which the Pope saw as a divine instruction to free the slaves held by the Muslims in North Africa. Innocent thereupon established the Order of the Redemptionists, whom he liked to call the Trinitarians. The Pope gave the saint the property next to the Arch of Dolabella in the ruined aqueduct for his convent and church. de Matha spent the rest of his life freeing slaves. On one of his trips to Africa he brought back 120 souls imprisoned in Tunis, buying their freedom with funds he raised in Rome and France. Augustus Hare relates that on the return voyage the ship lost both helm and sail in a great tempest, but all were saved when the saint knelt the entire time without ceasing at the foot of the crucifix.

|  |  | The church as you see is small and so beautifully bathed in white. It is seldom open, but surely try to enter. The greatest jewel here is not in the church at all. When the church was built in the time of the Cosmati in the twelfth century, there was a portal on the east side, in what is now the mammoth brick wall facing onto the busy street and the Piazza Navicella. Here the Cosmati made the famous wall mosaic of the Freed Slaves, one black, one white, Jesus firmly holding the arm of each. The father Cosmati signed the work and tells us that his son assisted him. | From across the Piazza Navicella we see the eastern wall of the grounds for the church of San Tomasso in Formis, which lies on the other side. The portal with the Mosaic of the Freed Slaves was once the entry into the Hospital of Saint Thomas. The Arch of Dolabella is on the right; the room behind the little window above the arch was Tomasso's home for several years. | |

Which brings us to the end of the first half of our walk up the ancient Clivus Scauri. On our next walk we will visit the Navicella and the “Sphinx of the Caelian” the Stefano Rotondo.

Copyright Greg Pulles 2023 All rights reserved

| | | | |