The Ceiling of the Sistine Chapel by Michelangelo Buonarotti | |

|

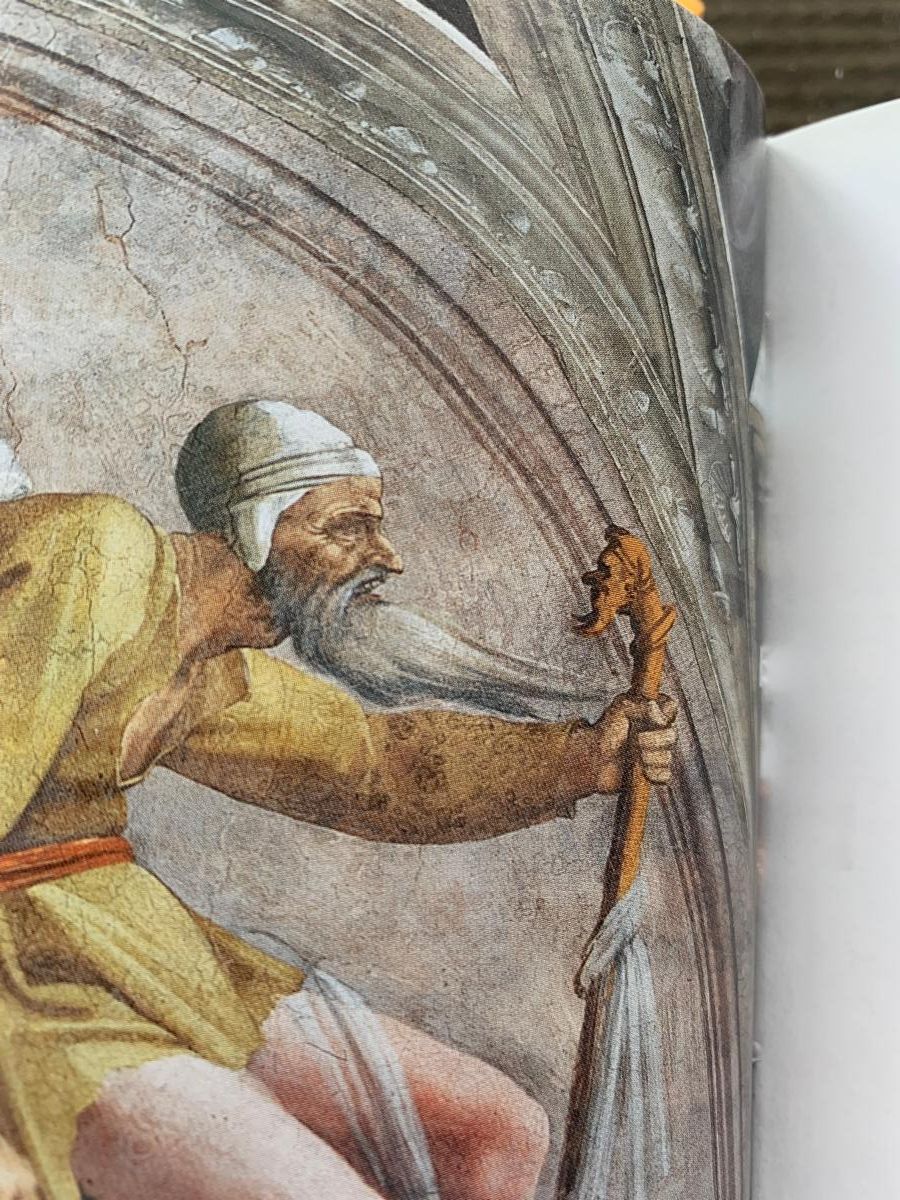

You aren't allowed to take photos in the Sistine. I have a number of books on the Sistine that have photographs galor. These include Italian Frescoes, High Renaissance and Mannerism, by Julian Kliemann and Michael Rohlmann, photography by Antonio Quattrone and Ghico Roli, Michelangelo and Raphael in the Vatican by Edizioni Musei Vaticani (photo above), photography by F. Bono, A Bracchetti, M. Carrieri, M. Sarri, and P. Zigrossi, The Vatican All the Paintings by Anja Greber, Michelangelo, by Frederick Hartt, and finally Paintings in the Vatican, by Carlo Pietrangeli. I highly recommend all of these to you. The best narrative about Michelangelo's Ceiling is without question Ross King's Michelangelo and the Pope's Ceiling, but the contemporary Renaissance works--Giorgio Vasari's The Life of Michelangelo and Ascanio Condivi's The Life of Michelangelo are also invaluable, as is Layard's the Italian School of Painting from the nineteenth century.

An Overview

Michelangelo was compelled by Julius II della Rovere (1503-1513) to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. The vault of the Chapel built by his Uncle Sixtus IV (1471-1484) had badly cracked, and the repairs were unsightly, and the starry sky no longer shone over the congregation. We will never know for certain whether, as Michelangelo alleged, his antagonist Donato Bramante (1444-1514) put it in the pope’s head to hire Michelangelo in the hopes that the artist would fail in this medium in which he had little experience, or whether the pope, who had certainly marvelled at Michelangelo’s David and Pieta, sought him out for his unsurpassed talent. In any event, the Sistine ceiling turned out to be Michelangelo’s greatest success.

In 1507 Julius had forced Michelangelo to stop work on the pope's tomb at San Pietro and come to Bologna to make a colossal bronze statute of the pope to celebrate Julius’ conquest of the city, and so the pope saw once more the man’s incredible gift. Michelangelo had resisted the Sistine commission not only because he suspected the scheming of Bramante but also because he wanted to finish the pope’s tomb, which he had begun in 1505, but for which he had little to show save the mountain of marble he had had sent to Rome from Carrara. In the end, Michelangelo signed the contract for the ceiling, and began preliminary work May 10, 1508. He was to finish in the late fall of 1512, just months before Julius’ death.

Michelangelo began by having the old stucco on the ceiling chiseled off, a new underlayment applied, and scaffolding erected (his invention of course). The pope had envisioned the Twelve Apostles for the vault, but Michelangelo convinced him that the subject should be multiple scenes from the Old Testament. Michelangelo’s final design had some 400 separate figures. The result here was “the greatest triumph that modern art has known.” Michelangelo had more than mastered the buon fresco (“true” fresco-- working with wet as opposed to dry plaster) technique, and we can see after the twentieth century cleaning his surprising and awesome power in using brilliant colors that quite literally stun the visitor upon his entry.

Michelangelo progressed rapidly in his fresco technique as he went along, expanding his colors to include a cooler range of tones, and slowly but surely increasing the size of his day’s work (the gironate--the section of plaster that remains fresh for just one day). Michelangelo was to have in his colors a “luminosity never before seen.” To make his figures he used what has been called a “shot silk” color scheme versus traditional chiaroscuro.

To begin with he used preparatory cartoons for the scenes on the vault, but when he got to the lunettes he often drew directly onto the base layer of plaster. When it came to the fictive architecture we see throughout, such as the cornice, he used string, nails, and rulers to make direct incisions into the plaster. For the most part he used what is called spolver--pouncing--transferring his cartoon to the plaster by first tacking the cartoon to the plaster and then pricking holes onto the cartoon along the main contours. Pounce, a fine charcoal dust, was then applied to the cartoon, which was then taken down leaving the outline on the ceiling.

When you enter the Sistine, it is best I think to take in the first two lower registers painted by those who came several decades before Michelangelo (Perugino and Botticelli leading the programme)—the Life of Christ and the Life of Moses, and the row of pre-Constantinian Popes that travels around three sides of the Chapel. Leave Michelangelo's Last Judgment--the Giudizio-- on the west wall for last.

For Michelangelo’s paintings, work from the bottom up, finishing with the Creation of Adam in the central vault, certainly the most famous painting of all time. Here are the five groupings for you.

1.Ancestors of Christ

2.Prophets and Sibyls

3.Pendentives--the Saving of Israel

4.Ignudi

5.The Story of Creation and the Story of Noah

First, at the lower level, in the spandrels around the windows, and in the severies above the windows, are the Ancestors of Christ, taken from the Genealogy of Jesus in Matthew and Luke's Gospels, some 90 figures. These are all given to us as family scenes, with plenty of children and plenty of simple family interaction.

Next come the Prophets (7) and Sibyls (5), colossal figures in dazzling color and my favorites on the ceiling. In this series Michelangelo broke spectacular new and untraveled ground. These figures are by far the largest figures in the ceiling. Each sits in a niched throne, with putti on the string courses. “They embody the highest ideas of inspiration, meditation, and prophetic woe.” Austen Layard. Michelangelo’s Prophets had predecessors in pictorial art, especially in the Sciences of the Cloisters at Santa Maria in Novella. But the Sibyls had no comparable antecedent. Michelangelo painted these as a unique type of being, totally unconcerned with human matters, and not really sweetly feminine, or sympathetically human, and not Jewish or Christian, certainly not a witch nor a grace, yet “living creatures, grand, beautiful, and true,” painted “according to laws revealed to the great Florentine genius alone.”

Then come the pendentives in the corners, four scenes representing the preservation/saving of the Jewish people—David slays Goliath, Judith cuts off the head of Holofernes, The Brazen Serpent and The Crucifixion of Haman from Moses.

Finally In the central oblong flat section of the vault Michelangelo placed his nudes-the Ignudi (who sit around the five smaller panels) and nine pictures from Creation and Noah, four large panels and five small panels:

1.God Separating Light from Darkness

2.God Creating Sun, Moon, and Plants

3.God Separating Sky and Water

4.The Creation of Adam

5. The Creation of Eve

6.The Temptation and the Fall

7. The Sacrifice of Noah

8.The Flood

9.The Drunkenness of Noah

The Ignudi are inventive masterpieces, troubling only in the aspect of female head attached to male body. The Ignudi sit on the projecting parts of the fictive cornices, and take up the space between each Scripture subject. At first called Athletes but soon called the Ignudi, they are too young to be called men and yet too old to be called youths. They have no wings and no beards. They do not have comparison in contemporary Renaissance figures, nor do they have an ancient precedent--they are a “new race” like the Sibyls. They are “fiddling” with bands of cloth and the ever present acorns of the Rovere family.

| |

|

My suggested perusal: take in the works of Perugino and Botticelli et al in The Life of Christ and The Life of Moses in the second register from the floor, then go to their Series of the Pre-Constantinian Popes in the third register from the floor, then go to Michelangelo. In the spandrels and severies are The Ancestors Of Christ, then adjacent to the severies, and in what I consider the next level up are the Prophets and the Sibyls. Then take in the four pendentives (only the Brazen Serpent and Haman are shown above, David slays Goliath and Judith slays Holofernes (which are above the main entrance door) are omitted. Above that in the central section of the vault is the Story of Creation and the Story of Noah and the Flood (mostly omitted above--they are closest to the main entrance), which has at the very center The Creation of Adam. The Ignudi surround the smaller panels in the Creation and Noah Stories. Finish with the Last Judgment.

Above I add these suggested groupings to an overall view of the Sistine, from Kliemann and Rohlmann.

| |

|

Michelangelo goes to work

Michelangelo was finally able to begin painting in the first week of October 1508. The task was daunting—a ceiling of some 12,000 square feet. For much of the next four years he would climb a forty foot ladder every day to the base of the scaffolding, the steps of which ascended yet another twenty feet. Every day began with the application of that day’s intonaco, the plaster upon which Michelangelo would paint. He employed a muratore, or professional plasterer who would slake the quicklime, and stir the mixture free of lumps and form it into a paste or putty. This paste would then be kneaded and mixed with sand, then stirred some more. The muratore would then apply the intonaco to the ceiling with a trowel or float, and would then wipe it with a cloth once or twice to roughen it a bit, then he would use a silk handkerchief to get any grains of sand off the surface. A skin would form in an hour or two, and during this time the design cartoon Michelangelo would have previously drawn was put up and the figures transferred to the surface with either the method called “pouncing” or with direct incising with a compass point. Finally Michelangelo could get to work with the actual painting. Michelangelo would have worked standing up, not laying down as tradition has it, although he would have had to crane his neck, tiresome enough.

Michelangelo worked from the east to the west, but he did not actually start at the most easterly part of the ceiling, but rather some fifteen feet from the entrance, above the second set of windows from the door. His first scene was the Flood of Noah (the large panels were ten by twenty feet), from Genesis. Michelangelo chose the location for his first scene because he thought this was the most inconspicuous part of the ceiling and he wanted to learn and allow for mistakes. It proved a smart move. Michelangelo loaded the scene with figures, giving way to “his passion for throngs of doomed figures in dramatic, muscle-straining poses.” King. Michelangelo practiced “painting” sculpture in the scene of the Flood, and we should strain to find “a bearded man bear-hugging the limp corpse of his son.” Only recently had the ancient torso of the Pasquino been dug up, and this served as Michelangelo’s model for the doomed man.

The Flood caused Michelangelo quite a few problems. Frescoists often had to make corrections they quaintly called pentimenti, or “repentances.” Hopefully before the plaster dried, the artist would see his mistake, scrape the plaster away and apply new intonaco. If the plaster had dried, the artist would have to chisel the plaster off, perhaps the entire giornata, or day’s work. Michelangelo had many pentimenti with his first panel, and after several weeks work, he actually chiselled all his work down and started over. Just one section survived this restart—the one group that huddles under a tent on the rock--and this is the earliest piece of work we see on the ceiling—the “start.” The Flood took twenty-nine giornate—painfully slow.

More troubles were to beset Michelangelo and the Flood. In January 1509 an efflorescence of salt appeared on the fresco. Michelangelo threatened to quit, and Julius sent Giuliano da Sangallo, one of Michelangelo’s few friends, to convince him to stay and to determine the source of the problem. Giuliano succeeded in both objectives, finding that Michelangelo’s Florentine assistants were using too much water to mix the intonaco—the lime they were using came from travertine, which dried differently and much more slowly than the lime they were used to using. The fresco also experienced mildew accumulation. This was due to Michelangelo having to apply secco (dry) touch-ups after the buon fresco dried, and these were susceptible to mold. Giuliano da Sangallo had to teach Michelangelo that he had to immediately remove any mold from the secco additions as soon as the mold appeared, else it would expand and destroy the fresco. The Flood ended up taking Michelangelo some two months to complete.

| |

| |

After the Flood, Michelangelo moved to the lateral spaces in the spandrels/lunettes. These were smaller spaces, and Michelangelo was able to complete the first two with eight giornate each. Here he was painting the Ancestors of Christ. On the South side he painted IOSAIS IECHONIAS SLATHIEL, and with his confidence growing he even painted some freehand on the plaster without the use of a transferred cartoon. Michelangelo chose to represent the ancestors as simple, not kingly, figures, and in a family group. Here in IOSAIS we have three people seemingly “slumped” on the ground.

Moving a little down the scaffold to the level of the lunette, which was always the last thing to be painted in each latitudinal band, Michelangelo was able to quicken his pace. These were flat vertical surfaces and he didn’t have to lean backward to paint, and he was also able to work without a cartoon. Each of these took him only three giornate to complete. Michelangelo was getting better and better using his colors to shape the figures: he would start with the shadows he wanted, then moved into the middle tones, and finally applied highlights.

For the spandrels and lunettes he used very very bright colors, and so we see “bright yellows, pinks, plums, reds, oranges, and greens,” which “imitated the effect of shot silk (woven silk of two colors which creates an iridescent appearance).” The lunette below the Flood has a woman with orange hair with a “shimmering pink-and-orange dress” who sits next to her husband who has a robe of brilliant scarlet.

The lunette of Josiah we see has Josiah arguing with his wife who is contesting with her squirming child-- a scene quite afar from Josiah’s biblical warrior exploits. In the adjacent spandrel we have another scene of common folks in common settings: a sleeping husband, with his wife sitting on the ground with cradled baby.

Michelangelo was to paint ninety-one figures into the Ancestors of Christ series in the lunettes /spandrels. All of these figures are in poses of routine life, taking care of children, grooming themselves, winding yarn and the like. Michelangelo did something else unusual here—he painted lots of women into the scenes, some twenty-five in all. Not all of the scenes are tranquil, and many of the Father-Mother-Child trios are full of anger and sloth and boredom. Boaz is my favorite--perhaps Michelangelo himself, scowling at his face on the top of his cane, which has his likeness.

|  | |

Michelangelo painted the first of his seven Prophets six months into the Sistine project. He was now confident of his frescoing skills. The Prophet Zechariah (above, Musei Vaticani) was placed over the main door, a conspicuous place which already held the Rovere Coat of Arms (a scrub oak—“Rovere”—with branches carrying twelve golden acorns). Most think Michelangelo painted Julius II here, since the Prophet has all the features of Julius—tonsured head, long Roman nose, and the look of the Rovere anger. Moreover the Prophet is dressed in the Rovere colors of blue and gold.

Michelangelo painted the first two pendentives on the East side--David Slaying Goliath and Judith cuts off the head of Holofernes (the head has the likeness of the artist). The Holofernes is the best here; the David is mediocre for the great one.

| |

In the summer of 1509 Michelangelo went on to his second scene from Genesis, the Drunkenness of Noah, painted on the easternmost of the nine episodes of Genesis that would occupy the central vault. This scene took even longer than the Flood, thirty-one giornate. The last Noah scene (six by ten feet) is chronologically out of order. The Sacrifice of Noah gives us Noah with his extended family thanking God for their survival from the flood, which had finally receded. After the Sacrifice was finished in the autumn of 1509, Michelangelo was about a third of the way completed (4000 square feet), which included three prophets, eight ignudi, two spandrels, four lunettes and two of the pendentives—two hundred giorante.

Which brings us to the five sibyls on the Sistine ceiling—these were the ancient soothsayers, whom Saint Augustine somewhat legitimatized by matching their predictions with the Virgin Birth and the Resurrection. The sibyls were seen as having prepared the pagan world for the Coming of Christ. They became a popular subject for Renaissance artists. Michelangelo had begun with Delphica, who had told Oedipus that he would kill his father and marry his mother. One of her prophecies was interpreted as foretelling of Jesus’ Crown of Thorns. Michelangelo took twelve days to paint Delphica (Musei Vaticani), whom he depicted as a “young woman with parted lips, wide eyes, and a faint look of distress, as if she had just been startled by an intruder.” King. Her beautiful headdress is painted in blue smaltino, and is perhaps taken from the Pieta. Michelangelo would go on to paint four more sibyls. Cumea (Musei Vaticani) he painted as an old woman, a “grotesque behemoth.” She has long arms, great biceps and mammoth shoulders, which dwarf her head. One of the two children astride Cumea gives her the Renaissance equivalent of “the finger”—which Italians still call the “fig”--with his thumb between his index and middle finger. Even Michelangelo could kid once in a while.

|  |  | |

In early 1510 Michelangelo moved to the large panel next to the Sacrifice of Noah. He was now close to the center of the vault. He painted The Temptation of Eve and the Expulsion from the Garden, and he did it quickly, in only thirteen giornate. The scene has two parts: on the left Adam and Eve take the forbidden fruit, and on the right an angel expels them from the garden. The snake of the devil has a female body and head, she hands the apple to Eve, while Adam (contrary to the Bible) reaches into the tree for one. This fresco has only six figures in it, the least number so far for Michelangelo, whose figures are getting larger. Here Adam is ten feet tall. Note the difference between the two Eves—one young and vivacious (said to be the most beautiful woman Michelangelo ever painted), the other an old hag with awful hair.

After the Garden, Michelangelo completed two more lunettes and spandrels, Ezekiel, the Cumean Sibyl, two pairs of Ignudi (Musei Vaticani), and the fifth Genesis scene, The Creation of Eve, which sat directly over the marble screen that separated clergy from lay in the chapel below. There were only three figures in the Eve, and Michelangelo was able to complete it in just four giornate. In the Eve, Michelangelo painted his first God the Father, and here he made him a “handsome old man with a white, wavy beard and a flowing lilac robe.” Here he used no foreshortening, and for many this is his weakest scene, caused in part by his decision to make the figures only a few feet tall.

Michelangelo continued with his Ignudi, inventing one new facial expression after another.

|  |  | Ezekiel (Musei Vaticani) was a clear success, larger than life, a muscular colossus sitting on a throne. His body turns to the right, he is in profile, heavily in contemplation, with brilliant eyebrows and jaw. Ezekiel joined Isaiah, who is beneath The Sacrifice of Noah, who has a furrowed brow from his contemplation, and is equally as handsome with his wonderful hair. |  | |

Four impressive Ignudi are at the sides of Eve, together with the yellow ribboned bronze medallions (all the medallions were painted a secco or on dry plaster) which each bore a scene from the Bible, the most popular here the scenes from Maccabees.

By the middle of the summer of 1510 Michelangelo had finished half the vault. Unfortunately it was at this point that the pope went to war with the French and left Rome, making it impossible for Michelangelo to unveil his work as he had planned. No work was done for the rest of 1510 and the first half of 1511, except for cartoons, which included the Creation of Adam. In June of 1511 the pope returned to Rome, and on the feast of the Assumption Michelangelo was allowed to unveil the half of the ceiling he had finished. Everyone of importance in the city (including Bramante and Raphael) was present for the mass in the Sistine, and they were not disappointed. Raphael was so impressed that he is said to have tried to steal the balance of the ceiling commission from Michelangelo, and he painted Michelangelo into his School of Athens as Heraclitus, the pensieroso, “the thinker,” using Michelangelo’s “new and wonderful manner of painting.”

Michelangelo also learned from the unveiling: his figures were too small when seen from the floor far below. He decided to greatly increase the size of the figures in the remaining scenes from Genesis. The first scene he painted was to become his most famous, the Creation of Adam. It took him sixteen giorante, and he started with Adam. Here was a “flawless human specimen” in keeping with the supreme Renaissance goal of bringing a figure alive. Michelangelo’s depiction of God was unique for the times. The Father appeared in early Christian art as a hand descending from the heavens. As He appeared more human as the early Renaissance progressed, He was shown as a young man. Michelangelo gives us an aged God, flying through the air, in full length, with bare legs.

|  | |

After Michelangelo finished the figures on either side of the Creation, he moved on to the seventh scene from Genesis, one of the days of creation, which may be The Separation of Land and Water, or The Separation of the Earth and the Sky, or The Creation of the Fishes. Only God and his small angels are in the scene. God is magnificently foreshortened, painted di sotto in su (“seen from below”) to give the accurate illusion of three dimensions on the flat ceiling. Bramante had said that Michelangelo, being a sculptor, did not know how to foreshorten. Well, Michelangelo certainly learned quickly enough. Michelangelo has God “tumbling toward the viewer at a forty-five degree angle to the vault’s surface.” From the floor God seems almost completely upside down.

It was shortly after this that Michelangelo painted perhaps the ugliest person on the celing, Boaz, in one of the lunettes. Boaz, though he was gentle and generous, was painted by Michelangelo as a snarly old man who carries a cane that has the same ugly likeness on the handle. Michelangelo painted other ugly figures in the smaller spaces, including the two dozen naked men who wear rams’ skulls and who are kicking and flailing about. He also painted his own homely figure into the fresco, in more than one spot. We can see him as the head of Holofernes—with his beard and flat nose.

In July 1512 Michelangelo finished the last two of the scenes from Genesis on the central vault of the ceiling, the Creation of the Sun, Moon, and Plants (the third and fourth days of Creation), and God Separating Light from Darkness (the first day). In the Sun, Moon and Plants we see from the rear on the left side God in the sky creating the few plants here, and on the right side we see a floating God pointing at the sun and the moon.

In the Separation scene, the ceiling scene with the fewest figures, Michelangelo places God in contrapposto with his hips and shoulders counterpoised, and masterfully foreshortens the figure. Michelangelo was by now racing to completion in order to finish while the aged pope was still alive (and before the French invaded and destroyed his work), and he took only one giornate to paint the Separation.

The Prophet Jeremiah (Musei Vaticani)(another Michelangelo self-portrait?) was one of the last figures painted, sitting on the north side on a throne. The prophet stares at the ground, his right hand supporting his chin, his beard and hair disheveled, the epitomy of “morose reflection.” Jeremiah is positioned directly across from the Libyan Sibyl, the last one of these painted. She has a sharply twisted body, and legs that bend opposite.

|  | |

|

Michelangelo painted the pendentives on the west wall in the fall of 1512, The Crucifixion of Haman (Musei Vaticani) and The Brazen Serpent. These are two of the best scenes on the ceiling. The contemporary art historian Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574) declared the Haman to be Michelangelo’s best: “certainly the most beautiful and most difficult.” Haman has both arms out, his hips turned, his left leg in and his weight on his right foot.

The Brazen Serpent was actually more difficult for Michelangelo, with twenty figures, and it took Michelangelo thirty giorante. The Laocoon was probably Michelangelo’s model here, which has a swarm of snakes killing the complaining Israelites. All of these figures, in orange and green, are expertly foreshortened. For most visitors these brilliant colors and the foreshortening make this scene the one that their eyes fix on first.

| |

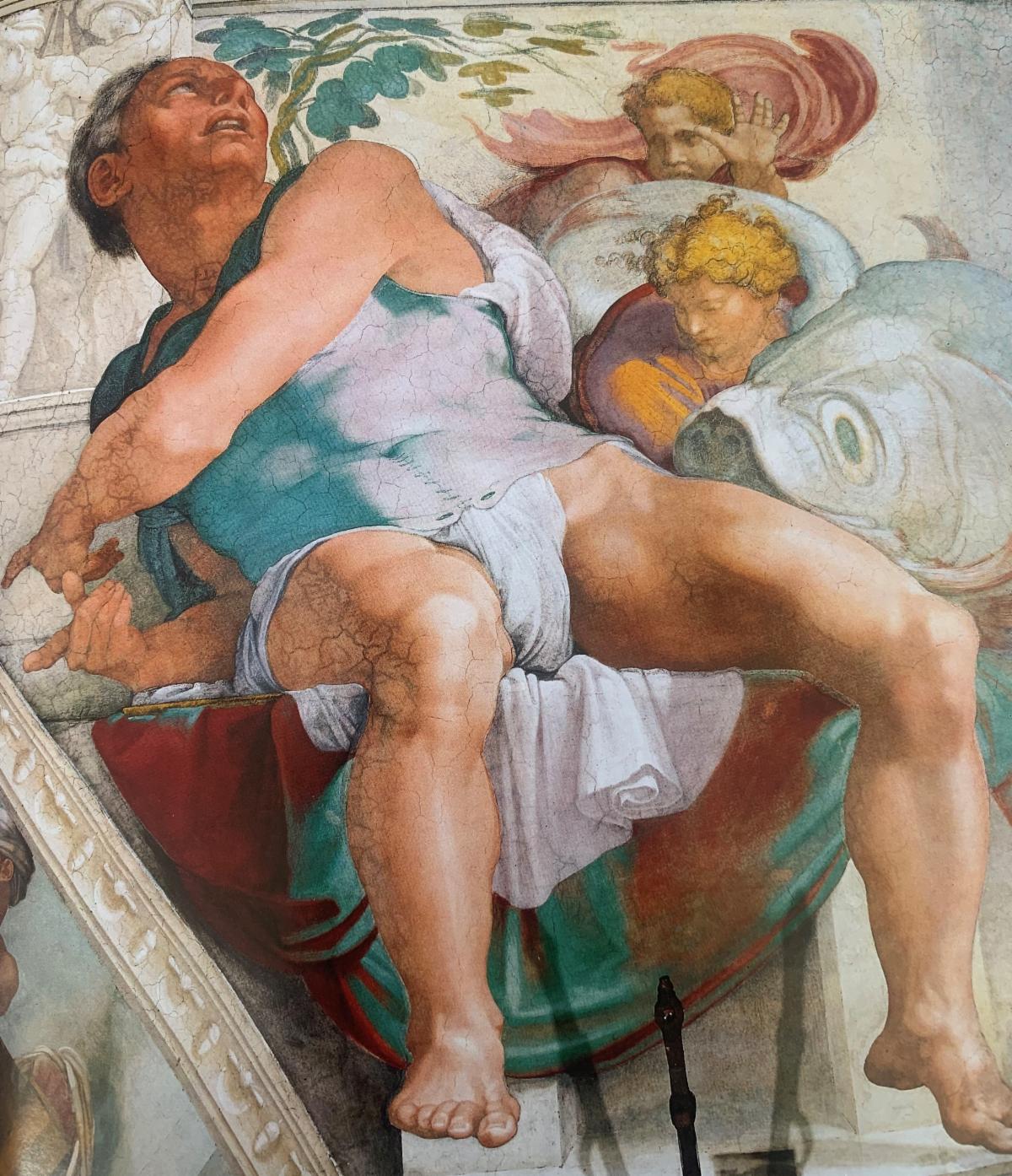

Michelangelo was now racing to the end of the work. He finished with the Prophet Jonah and the two accompanying Ignudi. The Jonah is regarded by many as his best, even better than the Creation. Jonah was in the space between The Crucifixion of Haman and The Brazen Serpent. Michelangelo’s contemporary Ascanio Condivi (1525-1574) voted this the best, for its foreshortening and perspective. This was a concave surface. Michelangelo has Jonah leaning backwards, his body twisted to the right, his head up and turned to the left. Condivi felt the foreshortening was without precedent since the “torso which is foreshortened backward is in the part nearest the eye, and the legs which project forward are in the part which is farthest.” Jonah was Michelangelo’s final retort to Bramante, who said the master “knew nothing of foreshortening. |  | |

Michelangelo’s final two ignudi were arguably his best. No other figures in art “came close to the brute visual force of Michelangelo’s naked titans.” King. One of these is bent forward at the waist, with his body tipped to the left, and his right hand reaching back. This was a pose which had no equal in originality or complexity either in ancient or contemporary art. Every Ignudo was different, and the facial poses and the flowing curly colored hair are indeed special (it is a bit hard to accept the femininity of the head and the masculinity of the body). These ignudi became Michelangelo’s unique trademark and they are certainly a special part of the ceiling.

The completed ceiling was unveiled at sunset on the Eve of All Saints, October 31, 1512, four years and some weeks after Michelangelo had begun his work. The accolades began and they never stopped. Michelangelo had achieved what everyone in art had thought the impossible. He silenced his critics, he achieved everything Julius could have hoped for in a work for all time. Bravissimo.

The Last Judgment

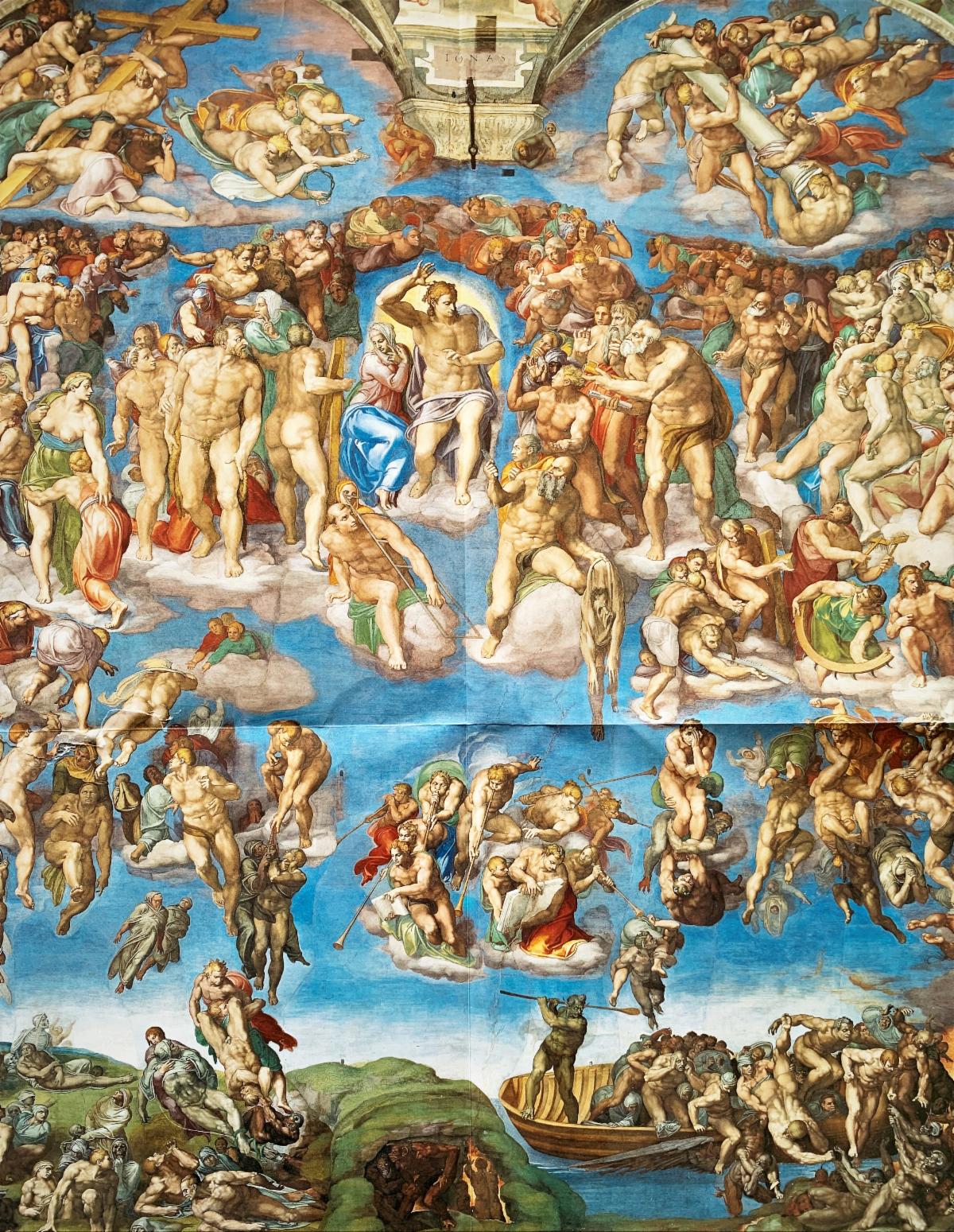

Twenty years after Michelangelo completed the Sistine ceiling, he was induced to return to paint on the west wall the Last Judgment, (Musei Vaticani) commissioned by Paul III Farnese (1534-1549) but conceived by Clement VII Medici (1523-1534). Michelangelo began in 1536 and finished in 1541. The celestial scene is filled with saints- the Baptist (camelskin), Peter(keys), Andrew (cross), Bartholomew (perhaps the most famous saint with his skin said to be a likeness of Michelangelo)(behind him is Michelangelo’s servant Urbino), Simon (saw), Blaise (wool-carder’s comb), Catherine of Alexandria (wheel), Lawrence (gridiron), the Good Thief (cross), Simon of Cyrene (cross)and Sebastian(arrows)the most recognizable. The angels with horns and the Books of Good Deeds and Evil are interesting too. And note the saved accompanied by the rosary to heaven!

I confess I am not an admirer of the Last Judgment—it is for me a letdown from the Ceiling. I don’t like the way Jesus is portrayed—he is in an uncomfortable pose as if he had just been splashed upon. Mary is not done with her usual and deserved beauty and charm. The nudity is also too much for me (how would the Baptist and Peter like being portrayed nude on a wall of a holy chapel?), prude that I am. It works on the Ceiling, but not here. At least Mary is clothed.

I also am depressed with those destined for hell. I know it’s a reality, I just don’t like to see all those horrific faces. The skeleton lower left pulls the dead from their graves. Charon in his boat is spectacularly scary (he has the eyes of Charcoal that Dante gave him), as are the fellow devils on the lower right. Minos with his serpentine tail and asses’ ears is lower right, above the door (a likeness of Biagio da Cesena who had criticized the nudity of the painting).

My favorite in the painting is the poor man who cover his face with his hand as the devil pulls him down from heaven, while a gigantic black bird bites him in the leg.

Which ends our visit to the Sistine, a very remarkable and stunning and memorable place indeed!

|  |  | |

|

In our next walk we begin our tour of San Pietro in Vaticano!

Copyright all rights reserved Greg Pulles 2023

| | | | |