THE NATIONAL MUSEUM OF WORLD WAR II AVIATION

* * *

COLORADO SPRINGS, COLORADO

| |

Last USS Arizona Survivor Passes | |

|

Lou Conter, the last living survivor of the sinking of the USS Arizona during Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, died April 1 in Grass Valley, California, at the age of 102 following congestive heart failure.

Conter was born in Ojibwa, Wisconsin, on September 13, 1921. His family moved several times before settling in Denver, Colorado, in 1930. Conter enlisted in the U.S. Navy on November 15, 1939; he joined the crew of the USS Arizona as a quartermaster on January 24, 1940.

| |

|

On December 7, 1941, Conter was on watch between the third turret and main deck when the Japanese attacked. When the Arizona was struck by a 1,760-pound bomb between the first and second turret, the explosion knocked Conter over. As the Arizona was burning and sinking, Conter helped the wounded, keeping them from jumping into oil burning on the water. Conter was still aboard the Arizona, standing in knee-deep water, when the abandon ship order was given. He continued to assist his fellow sailors, pulling men into his lifeboat. In the weeks afterwards, Conter helped with recovering the dead.

Conter received his Naval Aviator wings in November 1942, and flew PBY Catalinas with Patrol Squadron Eleven (VP-11). He was shot down twice over the Pacific. He went on to serve in the New Guinea campaign and in the European theater at the end of the war. During the Korean War, he served aboard the aircraft carrier USS Bon Homme Richard. He retired from the Navy in 1967 with the rank of Lieutenant Commander.

The Museum's eight-foot-long scale model of the Arizona honors all those who served aboard theship. The Arizona sank in nine minutes and 1,177 were lost. The ship's 334 survivors struggled to escape.

Colorado Springs resident Don Stratton, who also survived the attack and also saved others, died in 2020 at age 97. Following Pearl Harbor, Stratton was a crewman aboard a destroyer in several battles in the Pacific.

Story Credit: Rich Tuttle

Photo Credit: Wikipedia

| |

|

Museum Helps Schriever Space Force Base

Unit Connect With Its History

| |

|

The Museum is helping a unit of the U.S. Air Force Reserve connect with its World War II past. The 310th Space Wing (SW) at Schriever Space Force Base east of Colorado Springs has lineage dating back to WWII, when it began as the 310th Bombardment Group (BG).

The 310 BG was activated on March 15, 1942, and flew North American B-25 Mitchell medium bombers like the Museum's own B-25J "In The Mood." It deployed to North Africa and also was based in Italy. Today the 310 SW operates key space-based systems and provides space-related services.

A 310 SW video, shot March 27 in the Museum's Kaija Raven Shook Aeronautical avilion, is intended to familiarize members of the current 310 SW with the original 310 BG and its place in the history of WWII, and to boost pride in its roots.

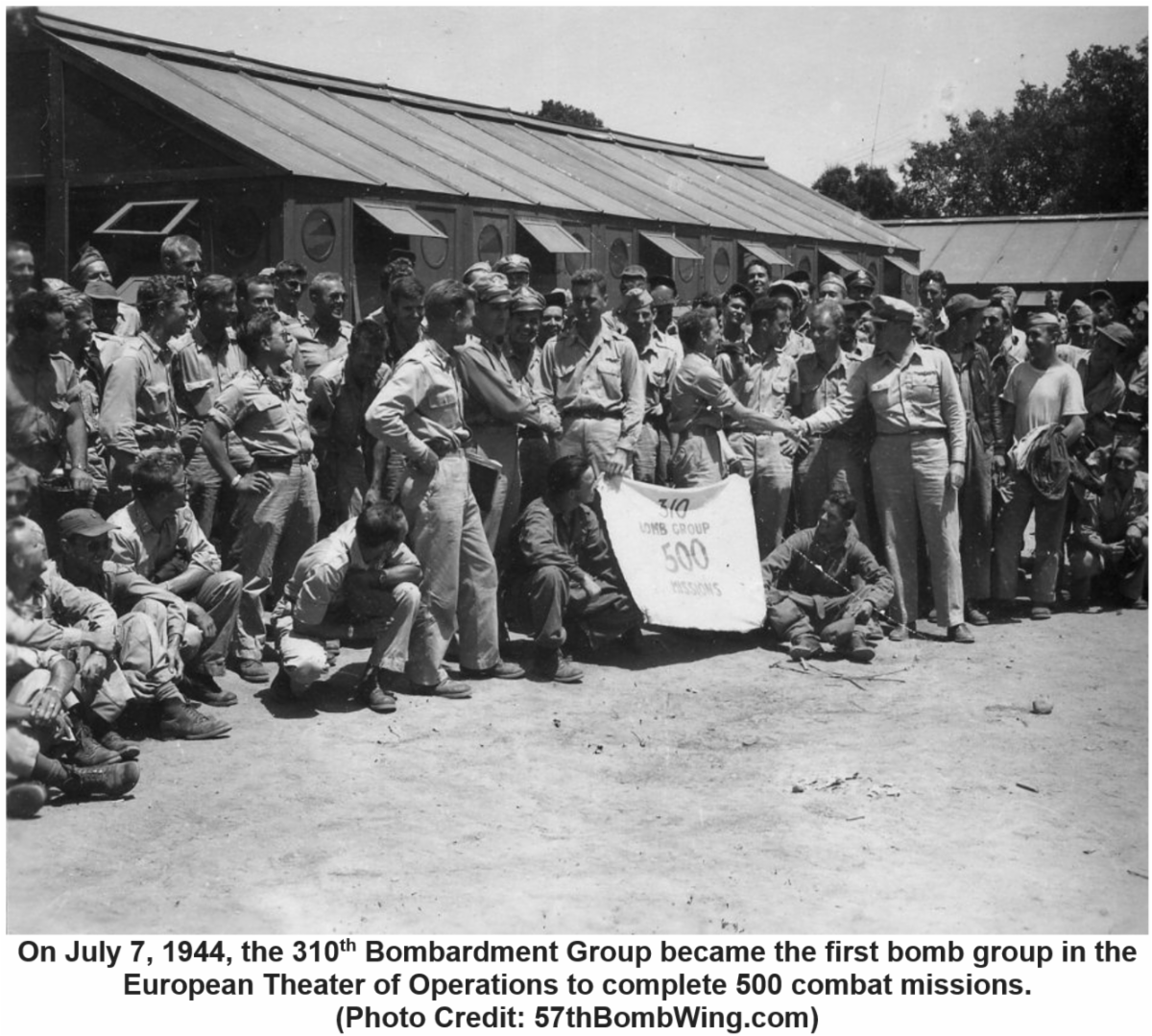

The 310th of WWII deployed to the Mediterranean theater in October-December 1942. It was assigned to the 12th Air Force and flew missions to Tunisia, Sicily, Italy, Corsica, Sardinia, Southern France, Austria, and Yugoslavia. According to M. Maurer's "Air Force Combat Units of World War II", it flew missions in North Africa from December 1942 to May 1943. Then, until July 1943, it carried out attacks in Pantelleria, Lampedusa, and Sicily. The group supported the Allied landing at Salerno, Italy, in September of 1943; assisted in the drive toward Rome from January to June of 1944. On July 7, 1944, the 310th became the first bomb group in the European Theater of Operations to complete 500 combat missions. It further supported the invasion of southern France in August of 1944, and hit German targets in Italy from August 1943 to April 1945.

|  | |

The 310 BG was awarded two Distinguished Unit Citations, Maurer writes. The first was for an August 27, 1943, mission to Italy when, in spite of persistent attacks by enemy interceptors and anti-aircraft artillery, it effectively bombed marshalling yards at Benevento and destroyed a number of enemy planes.

The second Citation was for a mission on March 10, 1945, in which, while maintaining a tight formation in the face of severe anti-aircraft fire, the group bombed a railroad bridge at Ora, a vital link in the German supply line.

|  | |

The video of the current 310 SW is being produced and directed by the unit's historian, Dr. Courtney Short. She and her Schriever Public Affairs crew of Master Sergeant Rachelle Morris and Technical Sergeant Devon Cole shot three segments in the Museum, all to tell about the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the response by B-25s of the Doolittle mission, and the effect of the raid on Japan itself and on American morale. The segments will be merged with others to tell the story of the original 310 BG, how it fits into the big picture of WWII, and how all that has led to the present 310 SW.

"Welcome to History Shorts," the historian said to the camera in the opening of the first segment. "Today we have a truly American story for you, one with heroes, one that is the stuff of legends."

| |

|

"When the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, it brought America into the war," she said. "and it stunned the American people. One Bombardment Group received orders for a secret mission to bring the fight to the Japanese homeland. No, that wasn't the 310th Bombardment Group. The 17th Bombardment Group [carried out] the mission that would become known as the Doolittle Raid. On April 18, 1942, sixteen b-25s took off from the deck of the USS Hornet and bombed military targets in five Japanese cities."

"The feat had never been done before," Short said from the right seat of "In The Mood," which was parked in the Pavilion. "And while the impact on Japanese industry was minimal, the psychological impact was immense, not only on Japan, but it lifted the spirits of the American people. The men became national heroes and legends of the [U.S.] Air Force."

The completed video can be viewed here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lxaR0oMISmI

Story Credit: Rich Tuttle

| |

|

Doolittle Copilot Recounted Famous Mission

in 2018 Museum Visit

| |

|

Editor’s note: This story originally ran in a 2018 edition of the Museum Newsletter after a visit by Dick Cole, Jimmy Doolittle’s copilot on the historic 1942 raid on Japan. We’re re-running it again, slightly edited, in recognition of the 82nd anniversary of that April 18, 1942, mission. Dick Cole died April 9, 2019, at age 103.

One-hundred-and-two-year-old retired Lieutenant Colonel Richard E. “Dick” Cole, last living member of the famous Doolittle Raid against Japan in 1942, was given a warm welcome at WestPac Restorations and the Museum on August 9 [2018].

To the applause of about 200, two items were presented to the Museum in a brief ceremony; a painting by artist Robert Moak signed by 43 of the Raiders, and a copy of the Congressional Gold Medal presented to the Raiders by President Barack Obama. Dick, his daughter Cindy Cole Chal, and Jim Bower, son of Raider Bill Bower, sat before Westpac’s B-25J “In The Mood,” a type very similar to the B-25Bs that were flown in the raid.

Eighty men, flying 16 B-25s from the carrier USS Hornet, stunned the Japanese by attacking Tokyo and other sites in Japan on April 18, 1942, just months after Japan’s December 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor.

“The purpose of the raid was two-fold,” Cole said at WestPac. “Number one, we were to let the Japanese know that their leaders were lying to them about their island couldn’t be hit by air,” a claim that Japan touted after the attack on Pearl Harbor. “The other reason was for the morale of the Allies, and mainly the United States.”

Then-Lieutenant Cole, flying as co-pilot in the lead plane with mission commander, then-Lieutenant Colonel Jimmy Doolittle, said they expected to be jumped by fighters and attacked by anti-aircraft fire.

| |

|

But, Jim Bower said, the Raiders “flew over Japan at noon on a Saturday and, by the grace of God, the Japanese had just finished a nationwide air-raid drill so they had smoke-bombs and everything going off all over Tokyo. All the [Japanese] airplanes were up in the air, but they weren’t armed so [the Raiders] flew right through the middle of Tokyo, dropped all their ordnance and lit out.”

Each Raider aircraft had a target; Doolittle’s was “Northwest Tokyo because we had fire bombs, and the fact that it was Northwest Tokyo was the bombardier’s dream,” Dick said. “He could drop them anyplace. But the main thing was that we didn’t have any [fighter] interceptions until we were leaving. We had a little bit of flak, but that was it.”

After the raid, Cole said, the Raiders felt they had met the goal of letting the Japanese people know their leaders were wrong about the impossibility of American air raids and had boosted Allied and American morale. The Raiders “were pretty well happy [that] the service we provided” was just as intended.

“The daring one-way mission...electrified the world and gave America’s war hopes a terrific lift,” the Air Force says today.

Initially, however, Doolittle himself was concerned. All but one of his B-25s had crashed in China, either along the coast or inland. The one that didn’t crash wound up in Vladivostok (Soviet Union) because of concerns it didn’t have enough fuel to make it to China.

The idea was for the planes to land at airfields along the Chinese-occupied coast and to later carry on the fight against Japan. But a Japanese vessel’s discovery of the Hornet’s task force hundreds of miles short of the intended launch point forced a decision to launch early, meaning that making it to China at all was problematic.

Doolittle and Cole crashed well inside China because a headwind that had been slowing them ever since the attack had turned into a tail wind. But the fuel tanks ultimately went dry.

“As we ran out of gasoline we bailed out in order of gunner, bombardier, navigator, co-pilot and pilot,” Cole wrote in 1973. “We were flying on instruments at approximately 9,000 feet at night with moderate to heavy rain. Our indicated airspeed was approximately 166 miles an hour, and so on the indication of fuel warning lights, we bailed out.”

Cole, 26 years old at the time, parachuted into a tall pine tree, coming to a halt about ten feet from the ground. He spent the night in the tree, and at daybreak started walking west. With Chinese help, he linked up with Doolittle and the rest of the crew.

At that point Doolittle “thought that because he had lost all the airplanes and didn’t know where the crews were, the raid was a failure,” Cole said at WestPac. But, he said, Doolittle was consoled by crew chief and flight engineer Paul Leonard who “told him that they’re going to promote you to general and you will get the Congressional Medal of Honor. And it so happened that it turned out that way.”

The day after the attack, Doolittle was promoted to Brigadier General – two grades above his rank. In July 1942, he was assigned to the 8th Air Force in England. In September 1942, he became commander of the 12th Air Force, which was readying for operations in North Africa. In November 1943, he took command of the 15th Air Force in the Mediterranean theater. From January 1944 to September 1945, he commanded the 8th Air Force as a Lieutenant General.

| |

Doolittle Raid details (Graphic Credit: Encyclopedia Brittanica) | |

|

The 12th Air Force included three groups of Martin B-26 Marauder bombers, and a number of Raiders wound up as crewmen of those bombers. Paul Leonard became Doolittle’s personal crew chief; he was killed in action in Algeria on January 5, 1943. Five other Raiders also were killed in North Africa.

Of the 80 men on the raid, 19 lost their lives in World War II, 17 in the first year following the raid, according to one count. Twenty-eight were assigned to the China-Burma-India (CBI) theater after the raid. These included the entire crews of Planes 4, 10, and 13, and Cole himself.

Cole was one of the first pilots to fly cargo missions from northeastern India over “The Hump” of the Himalayas into China to supply Chinese forces and the American Volunteer Group (AVG) under General Claire Chennault.

Cole returned to the U.S. for six months after that year-long tour, then went back to India, joining Colonel Phil Cochran’s Air Commandos operating into Burma. He flew C-47s for another year, towing troop-carrying gliders, and then returned to the U.S. with the end of the war in 1945. (Read more on Colonel Cochran and the Air Commandos in our Jan – Feb 2024 Issue here: https://myemail.constantcontact.com/January-February-2024-Museum-Newsletter.html?soid=1102286017538&aid=TOl-Ewmv0kU).

Eight Raiders were captured by the Japanese immediately after the raid; four died as prisoners, three by execution and one from starvation. Four more were captured by the Germans later in the war, and two of these were involved in the famous 1944 Great Escape from Stalag Luft III, a German prisoner-of-war camp.

Due to the severity of their injuries, two of the Raiders were separated from the Army Air Forces in 1944.

Ted Lawson, pilot of Plane 7, suffered a compound fracture of his left leg, a lacerated bicep, and severe facial injuries when he and co-pilot David Davenport crashed near a small island off the coast of China and were ejected through the windscreen of their B-25. Lawson and newspaper columnist Bob Considine wrote the best-selling 1943 book, “Thirty Seconds over Tokyo,” which also became a hit movie. Lawson was retired from service in 1945. He died in 1992.

“I do think about the other guys and it kind of keeps me flying straight and level,” Cole said at WestPac.

Cole’s daughter Cindy said at the event that her father and the other Raiders were always surprised to have received so much attention. She said 16 million men and women were in the service during the war, and that 34 million other Americans built the ships, planes, tanks, and other equipment to support the war effort.

The Raiders “have always been flabbergasted that they’ve been singled out to get as much attention as they’ve gotten over the years.”

Still, she said, the Raiders made the first attack on Japan itself after Pearl Harbor. Feelings in the country were so strong that “fifth graders would have volunteered to go and bomb Japan.” The Raiders, she said, “were just in the right place at the right time to be able to help their country, and they’ve always said that. They were very happy to do it. And it worked.”

“If you want to enjoy freedom, you have to step forward in case of emergency” Cole said. “It turns out...freedom is not cheap.”

Story Credit: Rich Tuttle

| |

Our volunteers restore aircraft, lead tours, greet visitors, plow snow, create art for sale, and help with every aspect of the museum. We love our volunteers! |  | |

Are you interested in joining the Museum cadre of 220+ volunteers? A little birdie tells me that the Front Desk is recruiting right now!

From Debi Klaers:

The Admissions Team of the National Museum of WWII Aviation is currently seeking friendly, courteous, and available volunteers to join our team. The duties include:

customer service, admission, gift shop transactions, answering telephones, giving museum directions, and making overhead announcements. Volunteers are needed for the morning and afternoon shifts. The Museum is going to summer hours on May 20, 2024, and we will be open seven days a week. The Museum returns to winter hours mid-September, when we will be open five days a week (Tuesday-Sunday).

If you are interested please contact Debi Klaers via email or call the front office 719-637-7559, or at debi@worldwariiaviation.org

Here are some of the volunteer position descriptions:

FRONT DESK – Oversees daily museum operations in Admissions, ie; opens and closes terminals, takes care of the bank and keeps cash drawers full and balanced, checks in guests, sells guided tours, gift shop memorabilia, creates monthly schedule for volunteers working admissions, schedules group tours, events (large and small), makes intercom announcements regarding tour times, provides information requested by phone inquiries and for the general public. Greets customers, either validating prepaid tickets or selling new tickets, discussing topics about the museum pertaining to their interests and completing various administrative jobs as needed. This position interfaces with the public and requires a positive attitude and the ability to focus when working with groups of people.

RETAIL DEVELOPMENT, GIFT SHOP AND SALES – Performs retail related tasks such as stocking, assembling retail displays, and back-office tasks. Creates aviation art for sale from historical airplane parts, aluminum, Plexiglas and other materials.

VOLUNTEER COORDINATOR – Works on activities to support the volunteer process, maintains associated data and forms, interacts with project or program leaders in the volunteer application and intake process, and recruits’ volunteers for events and activities. Computer and Microsoft Office familiarity and the desire to work with people are required.

FACILITIES AND GROUNDS – We are expanding this group and need volunteers to help with all aspects of maintenance, repair, and operation of the museum buildings and grounds. Typical duties include cleaning, servicing of facilities equipment, minor building repairs, mowing, weeding, and scooping and plowing snow.

EVENT OPERATIONS – We need additional staffing for event planning, event setup and preparation, supporting the event while it is in progress, and in returning the museum to operational status. Requirements for this position include the ability to work during the week, basic experience with planning and communication, the ability to perform physical labor and to be customer focused. The museum usually hosts 30 – 40 events a year.

EVENT PARKING – Many events require parking assistance to guide customers to the assigned parking locations. This position will help plan and support this event related parking. Requirements for this position include the ability to work during the week when events occur and to have the physical capability necessary to work outside, on your feet to assist event guests parking their cars.

DOCENT – Acts as a museum host and interacts with visitors throughout their stay at the museum. Conducts guided tours that provide historical context for museum visitors. Monitors museum galleries to ensure the security of aircraft and exhibits, and the general safety of museum guests. Docents are required to participate in an on-going training program where they acquire detailed and accurate knowledge of the museum’s mission, story line, artifacts and aircraft.

So how do you go about throwing your name into the hat to join the team? It’s easy!

Just go to https://www.worldwariiaviation.org/become-a-volunteer and fill out the application! Be sure to check the appropriate little boxes in the middle of the page for areas that you’d be interested in working, write out prior experience/qualifications in the big white box at the bottom, then click “Send” in the lower left corner.

That’s it!

Who knows, you might soon be working with ………

| |

Volunteer of the First Quarter Sandra McLaughlin | |

|

Sandra McLaughlin was named the Museum's Volunteer of the First Quarter, and was honored on Saturday, April 13, at an award ceremony and luncheon in our Hangar 1A at Colorado Springs Airport.

Sandra has been with the Museum since 2018 and "has done a marvelous job" in several capacities, said Debi Klaers, who oversees Museum events and runs the front desk. "Sandra is an absolute joy to work with and knows the Museum almost as well as I do, and for that I am most grateful," said Debi, wife of Museum President and CEO Bill Klaers. "Sandra will take on most any task and always sees it through to fruition."

She is "my second in command for events, tours, [and] shares the front office/admissions with me along with Merrick [Dunphy]," Debi said in a brief statement. "She is also my second in command with the Pikes Peak Regional Air Show and has done a great job in that capacity as well. Sandra works most all events if available and is absolutely reliable. She has done a few events on her own and did an extraordinary job. I couldn't be prouder of her and her accomplishments. Sandra is an absolute asset to the Museum and well deserving of this recognition and honor."

Sandra was born in Florida and grew up there. She and her husband Kevin moved to Colorado in 1997. She worked for the U.S. Postal Service for 35 years.

"Not only is [Sandra] a great asset for the Museum, but she's also one of my best gal friends in the whole world," Debi said at Saturday's event.

"It's great to be a part of this family," Sandra said upon receiving a certificate recognizing her contributions. "And I do consider this my family. I love all you guys."

Bill Klaers said Sandra is "a worker" and has done "a great job."

Klaers’ 70th birthday, which was the next day, April 14, was also celebrated at the event. Happy Birthday Bill!

Story and Photo Credit: Rich Tuttle

| |

The WestPac experts use highly detailed engineering drawings like this one, for the Curtiss SB2C-1A Helldiver, in their painstaking restoration of all aircraft. | |

This Helldiver, built in 1944, was damaged in a ground accident in Seattle, Washington, was used as a firefighter training aid, and then dumped into Lake Washington in 1945. It was acquired by Jim Slattery and was eventually sent to WestPac, on the campus of the Museum at Colorado Springs Airport.

Jim has been instrumental in acquiring some of the rarest WWII aircraft and bringing them back to historically accurate flying condition. Such is the case of this SB2C-1A, which when completed will be the only one in the world flying today. Jim and the Museum are honored to be the custodians of such aircraft upon completion, and proud to be able to share them with the world. The team at WestPac is working to the best of their ability to have the Helldiver completed and flying for the Pikes Peak Regional Air Show, August 17 & 18, 2024!

| |

Story Credit: Rich Tuttle

Photo Credit: Rich Tuttle and George White

| |

USAAF B-17 Bombers Deployed to the Soviet Union | |

On June 2, 1944, Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses from USAAF bases in Italy landed at a Soviet air base near Poltava in the Soviet Union; USAAF ground crews awaited their arrival. One hundred thirty B-17s, escorted by 70 North American P-51 Mustangs, had bombed a rail marshaling yard in Hungary and landed at three airfields in the Soviet Union. It was the beginning of "Operation FRANTIC," an effort that started with great hope but proved to be a largely irrelevant historical footnote. | |

|

It was an effort to strike German targets in Eastern Europe from bases in Italy and England. The concept, termed shuttle bombing, was for the bombers and fighters to take off from home bases in Italy and England, strike targets in Eastern Europe that were unreachable if the force had to recover at their home bases, land at airfields in the Soviet Union, rearm and reload, and bomb again while returning home.

The reality fell short of what was hoped. The bases that the Soviets provided were much farther east than desired and they were barebones with almost no facilities. Air defense was the responsibility of the Soviet Air Force. U.S. engineers with Soviet labor lengthened runways, installed Marsden steel matting, and developed taxiways. Target selection was subject to Soviet veto and the Soviets favored bombing near Red Army battle areas.

On the night of June 21, 1944, 150 German bombers launched a surprise attack on the overnighting USAAF aircraft at Poltava, in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. Over the course of two hours, forty-seven B-17s, two C-47 transports, and an F-5 reconnaissance aircraft were destroyed. Every B-17 and two F-5s were damaged. Two Americans were killed. Two hundred thousand gallons of aviation fuel went up in flames. The Soviets had nothing to show for their air defenses, but not for lack of trying. The other two bases were attacked on the next nights.

| |

|

In all, there were seven "Frantic" operations that ran from the Soviet airfields periodically through September 1944; each included several shuttle missions. As the European war’s Eastern Front moved gradually westward, the need for strategic strikes in Eastern Europe diminished. USAAF personnel departed in October 1944.

"Operation FRANTIC" was a strategic failure, as there were too few missions to affect the war effort. The Soviets, however, gained much -- aircraft, the Norden bombsight, and training in the concepts and techniques of long-range strategic bombing.

| |

|

Story Credit: Museum Curator and Historian Gene Pfeffer

Photo Credit: National Archives

| |

|

The Douglas Skyraider:

An Attack Workhorse Born in World War II

| |

|

The story of the Douglas Skyraider was traced in a special Museum historical presentation by docent and U.S. Air Force veteran Nick Cressy. He also told the story of the Museum's own Skyraider, one of the 29 operational planes in our collection.

In a January 13 presentation titled "The A-1 Skyraider: An Attack Workhorse Born in WWII," Cressy said the type was designed, developed, and flight-tested during World War II. He said the U.S. Navy wanted a carrier-based, single-seat, long-range, high-performance dive- and torpedo-bomber to replace the Grumman TBF Avenger and Curtiss SB2C Helldiver. It wanted a plane with greater range and higher performance that also could carry more ordnance. It chose the Douglas Skyraider, which flew for the first time on March 18, 1945.

| |

|

World War II ended, however, before it could be deployed, but it did see combat in Korea and is probably best known for its role in Vietnam. In addition to being operated by the U.S. Navy and Air Force, it was flown by the British Royal Navy, the French Air Force, the Republic of Vietnam Air Force (RVNAF), and others. Production ran until 1957 and 3,180 were built.

Cressy said the Douglas XBT2D-1 Skyraider competed with the Curtiss XBTC-1, the Kaiser-Fleetwings XBTK-1, and the Martin XBTM-1. Upon winning the competition, the Skyraider was ordered into production on May 5, 1945. It entered U.S. Navy service in 1946 and remained in American service until the early 1970s, a testament to its ruggedness and versatility.

The first Skyraider action of the Korean War came on July 3, 1950, when aircraft from the USS Valley Forge carried out the first of many combat support missions for the Navy and Marine Corps. Cressy said his father, who served as a Marine in the last year of the Korean War, "saw a lot of planes coming in for close air support" but that "it was wonderful to have the propeller planes go in because they'd hang around for hours [while] the jets would come in maybe once, maybe twice, and they were gone."

On May 2, 1951, Cressy said, Skyraiders made the only aerial torpedo attack of the Korean war, hitting the Hwachon Dam, which controlled flooding of two rivers. "The heavy damage wiped out electrical power over a vast area," said Robert F. Dorr in a Defense Media Network item dated August 14, 2012. "More importantly, the destruction of the dam broke up a planned enemy offensive. In every way, the damage inflicted by Skyraiders, and aerial torpedoes, exceeded expectations."

| |

|

During the Korean War, Cressy said, Navy and Marine Skyraiders were used with effect on such other targets as bases, tanks, trucks, outposts, roads, bridges, and rail systems. They also flew reconnaissance, electronic countermeasures, airborne radar and night-attack missions.

In Vietnam, Skyraiders were involved early on. In August of 1964, Navy Skyraiders flew in support of Operation PIERCE ARROW, a response to North Vietnamese torpedo boat attacks on the destroyers USS Maddox and USS Turner Joy in the Gulf of Tonkin. The incident led to the U.S. engaging more directly in the Vietnam War.

The Skyraider was not a match for North Vietnamese MiGs, but Skyraiders shot down two of the jets in separate engagements, Cressy said. In the first, on June 20, 1965, Skyraiders from the USS Midway were supporting a mission to rescue a U.S. Air Force McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom crew downed in northwest North Vietnam when two MiG-17s attacked. One was downed by Skyraider 20mm cannon fire and another was probably shot down.

The second engagement occurred on October 9, 1966, when Four North Vietnamese MiG-17s attacked four Skyraiders from the USS Intrepid as they were supporting a rescue mission. One was confirmed as shot down, a second as probably shot down, a third was heavily damaged, and the fate of the fourth was unknown. MiGs shot down three Skyraiders in later engagements.

The Skyraider's last U.S. Navy combat tour in Vietnam ended in February of 1968. As the USS Coral Sea transitioned to jet attack aircraft, its aging Skyraiders were replaced by the Douglas A-4 Skyhawk, Grumman A-6 Intruder, and LTV A-7 Corsair II. The Marines had already shifted to A-4s and F-4 Phantoms.

Meanwhile, starting in 1960, the RVNAF had begun operating Skyraiders with U.S. Navy training and support. In 1962, the U.S. Air Force took over that mission. That same year, the USAF acquired 150 Skyraiders for feasibility testing in several areas, including counter-insurgency and close air support. It trained more than 1,000 Skyraider pilots for service in Vietnam, while more than 300 were trained for the RVNAF. Training took place at Hurlburt Field, Florida.

In August of 1967, Cressy said, the USAF formed Skyraider squadrons for special operations and search and rescue squadrons. In 1968, they began flying from Pleiku Air Base in South Vietnam and Nakhon Phanom Royal Thai Air Force Base, Thailand.

| |

|

While the U.S. denied it, a war also was being fought in Laos and Cambodia. Skyraiders supported special operations teams in close air support missions from Nakhon Phanom, Udorn, and Ubon, also in Thailand; forward bases in Laos itself, and bases in South Vietnam. But 165 other RVNAF planes were flown to U-Tapaho Royal Thai Air Force Base in Thailand.

Upon the April 30, 1975, surrender of South Vietnam, most A-1s were destroyed and 40 or more were captured by North Vietnamese troops, Cressy said. A total of 165 RVNAF aircraft, including 11 Skyraiders, were flown from Bien Hoa, South Vietnam, to U-Tapaho RTAFB. On May 5 and 6, 1975, four Skyraiders -- including one that ultimately became the Museum's -- were flown to Thailand's Takhli Air Base.

A key player in this story was U.S. Air Force Brigadier General Harry Aderholt, commander of the U.S. Military Assistance Command, Thailand (MAC-THAI). He wanted to preserve the Skyraiders since they had shown their value in combat, but his main goal was to get as many American planes out of South Vietnam and back to the U.S. as possible, especially 31 Northrop F-5E/F supersonic fighters.

The four Skyraiders first went the port of Bangkok and were loaded on a ship. They were later acquired by David Tallichet, president of Military Aircraft Restoration Corp. in Long Beach, California. He stored them until 1986.

One came here to the National Museum of World War II Aviation in Colorado Springs. One went to the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum where it is awaiting restoration. Another went to the Cavanaugh Flight Museum in Addison, Texas. The fourth went to the Tennessee Museum of Aviation in Sevierville, Tennessee. At the 2019 Pikes Peak Regional Air Show at Colorado Springs Airport, three of the four flew together.

| |

|

The Museum's Skyraider, an A-1E model with the Navy Bureau of Aeronautics No. 132683, was delivered to the Navy in 1954, Cressy said. It was acquired by the Air Force in July of 1964 and assigned to the 1st Air Commando Wing at Hurlburt Field for training. It was then assigned to the Sacramento Air Logistics Area at McClellan AFB, California, for upgrades and application of camouflage paint in preparation for transport to Southeast Asia under the Military Assistance Program. From May 1970 to April 1972, it served with the 56th Special Operations Wing at Nakhon Phanom Air Base, Thailand. It was then transferred to the RVNAF.

Story Credit: Rich Tuttle

| |

See Our Latest YouTube Video Presentations! | |

|

If you haven’t been over to our YouTube page lately, just click here:

https://www.youtube.com/@nationalwwiiaviation/videos

... to view our latest videos of past museum special presentations. These include The Siege of Malta, B-25 Air Apaches, Battle for Guadalcanal, and more!

| |

Aircraft Carriers Were Vital to Allies and Axis in WWII | |

| |

Aircraft carriers and carrier-based aviation were central to the history of World War II because they played vital roles for the both the Allies and the Axis, said John Lynch, a U.S. Navy veteran and Museum docent.

"The British Royal Navy had aircraft carriers and used them very expertly" in the Battle of Taranto to destroy the Italian fleet; the Imperial Japanese Navy “utilized their aircraft carriers [with] great impact" in the Pacific, at Pearl Harbor, and in the Battle of Midway, for instance; and American carriers were used to significant effect in both the Pacific and Atlantic, Lynch said. The Pacific theater, he said, was "a succession of carrier-based battles, but also amphibious warfare that was supported primarily by aircraft carriers."

Addressing an audience in the Museum's Hangar 2 in a March 16 presentation titled "Aircraft Carrier Operations During WWII," he said four countries -- the U.S., Britain, Japan, and France -- had a total of 220 carriers during the war.

The U.S. had the most with 111 (24 fleet carriers, 9 light carriers and 78 escort carriers). Britain was next with 83 (12 fleet, 8 light, 44 escort and 19 merchant aircraft carriers, or MACs, converted from oil tankers and commercial grain transports). Japan had 25 (13 fleet, 7 light and 5 escort). France had one, a fleet carrier.

The U.S. Navy benefitted from carrier technology developed by the British Royal Navy, Lynch said. But, he said, while the Japanese made expert use of their carriers, they "didn't have [comparable] development because they didn't have the arsenal of democracy that we had operating here in the United States."

Carrier-based planes don't "take off" like land-based planes, they are "launched," Lynch said. Navigation and communication also are very different, and carrier aircraft don't land, they are "recovered."

Launching depended on how fast the ship was going, the velocity of natural wind, the payload of an aircraft, and its type, Lynch said. Catapults could be used if the payload was heavy, like a Mark 13 torpedo, of which the Museum has a volunteer-made replica. Hook-like devices on or near the main landing gear allowed attachment of a "bridle" to a "shuttle" in a flight-deck catapult.

| |

|

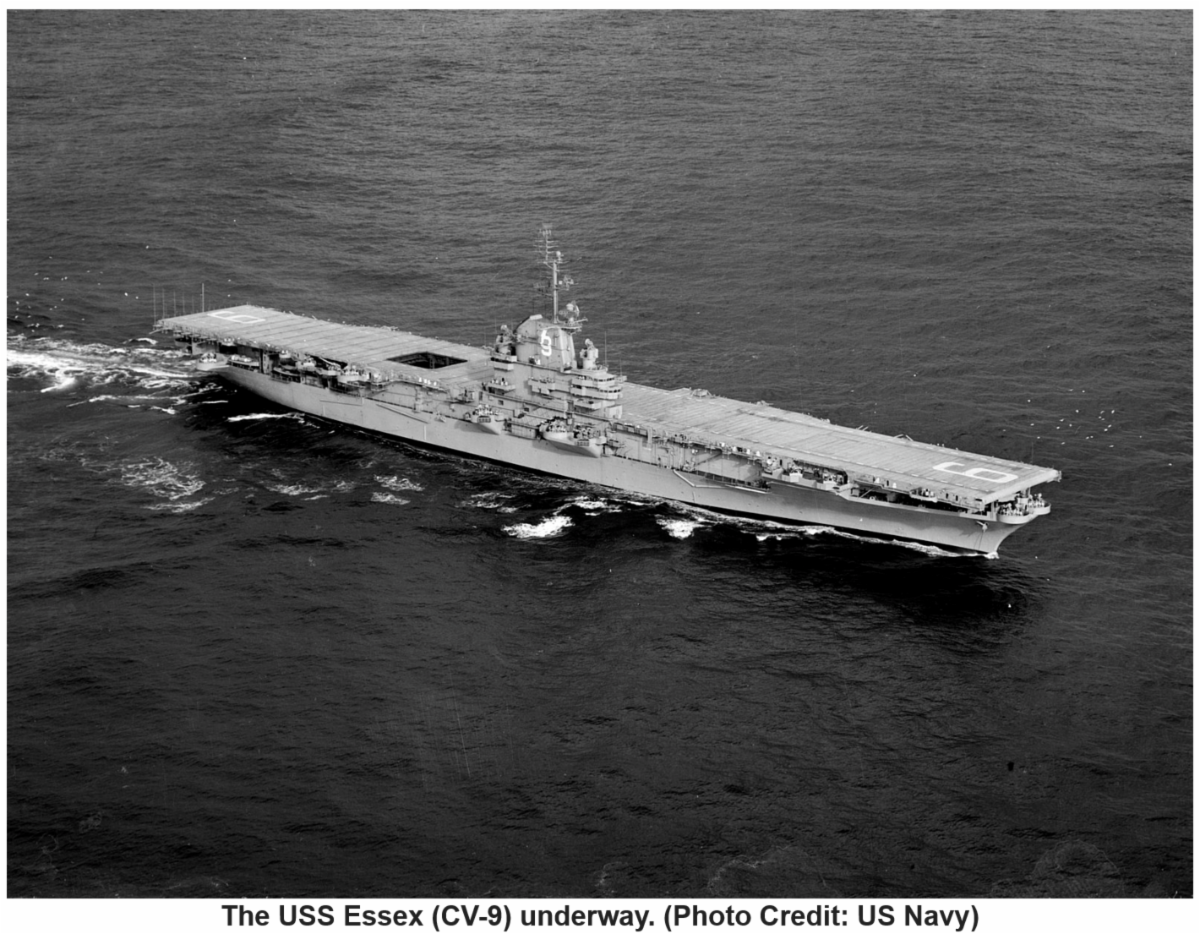

Essex-class carriers also had a "cross-deck" catapult to launch planes from the hangar deck. If planes were bunched up on the flight deck and timely reconnaissance of the enemy was required, for instance, it would allow a scout plane to be launched. It wasn't used often and was ultimately removed, Lynch said.

Navigation was over featureless water that may, in any case, be covered by clouds. There were no rivers, towns, or mountains to check against a map. "You need dead reckoning," Lynch said. That, among other things, means knowing where you are in terms of latitude and longitude, and knowing where the ship will be when you return. It means knowing your speed, having a good compass, and knowing about any crosswinds.

A little desk with a "maneuvering board" helped with all this. It slid out from under the instrument panel and, with a circular slide called the E6B, it depicted headings and ship location. The Museum’s SBD Dauntless dive bomber has such a desk.

"In addition to flying the airplane, trying to stay out of the way of people trying to shoot you down, dropping your bomb, and talking to your radio operator in the back seat, you also had to be navigating all the time," Lynch said. "And you were invested in the outcome because if you messed up your navigation, your dead reckoning, you're not going come close to the ship" on the way back from a mission.

As the war progressed, pilots had some help from the YE-ZB "Hayrake" electronic navigation system. It broadcast a signal from the carrier and helped a pilot understand where he was in an imaginary circle around the ship. There was a different code for every 30 degrees around the ship, and the codes changed every day. It worked relatively well and "a lot of people got back to the ship because of it," Lynch said.

| |

|

Recovery is probably the thing that most defines naval aviators, he said. "It's not magic but it takes some practice, and it is an example of very precise flying." And "airspeed is hugely important. There's very limited visibility” from the cockpit as a plane approaches a carrier’s deck, “and you're going to rely" on a Landing Signal Officer (LSO) "to help you bring the plane back on board.

“The dangerous thing...is you are flying right on the edge of a stall.... In most propeller-driven airplanes of WWII, that airspeed was about 69 to 70 knots."

“You pull the power back, that propeller [becomes] a fairly decent brake, and the plane falls out of the air onto the deck” at the “cut” signal of the LSO, Lynch said. “You don't land the plane, you crash it into the deck in a controlled fashion and it works pretty well, but it can be pretty scary. But it is an example of precision flying.”

The LSO would "grade" each landing and would sometimes be challenged by squadron officers.

Flight decks of American carriers in WWII were made of wood because it's relatively light, Lynch said. "We did that because if you add a lot of weight to the flight deck and the ship rolls, the extra weight is going to exacerbate the roll." Teak was used, and before the war most of it came from Indonesia. But that wasn't possible after the Japanese took Indonesia, so a number of other sources of the wood had to be acquired.

Controlled-crash landings meant the planes themselves had to be sturdy. In fact, the requirement to operate from carriers affected aircraft design in several ways, Lynch said. A close look at some of the planes in the Museum's collection -- including the Dauntless, Corsair, Helldiver, and Skyraider – will show how.

|  | |

|

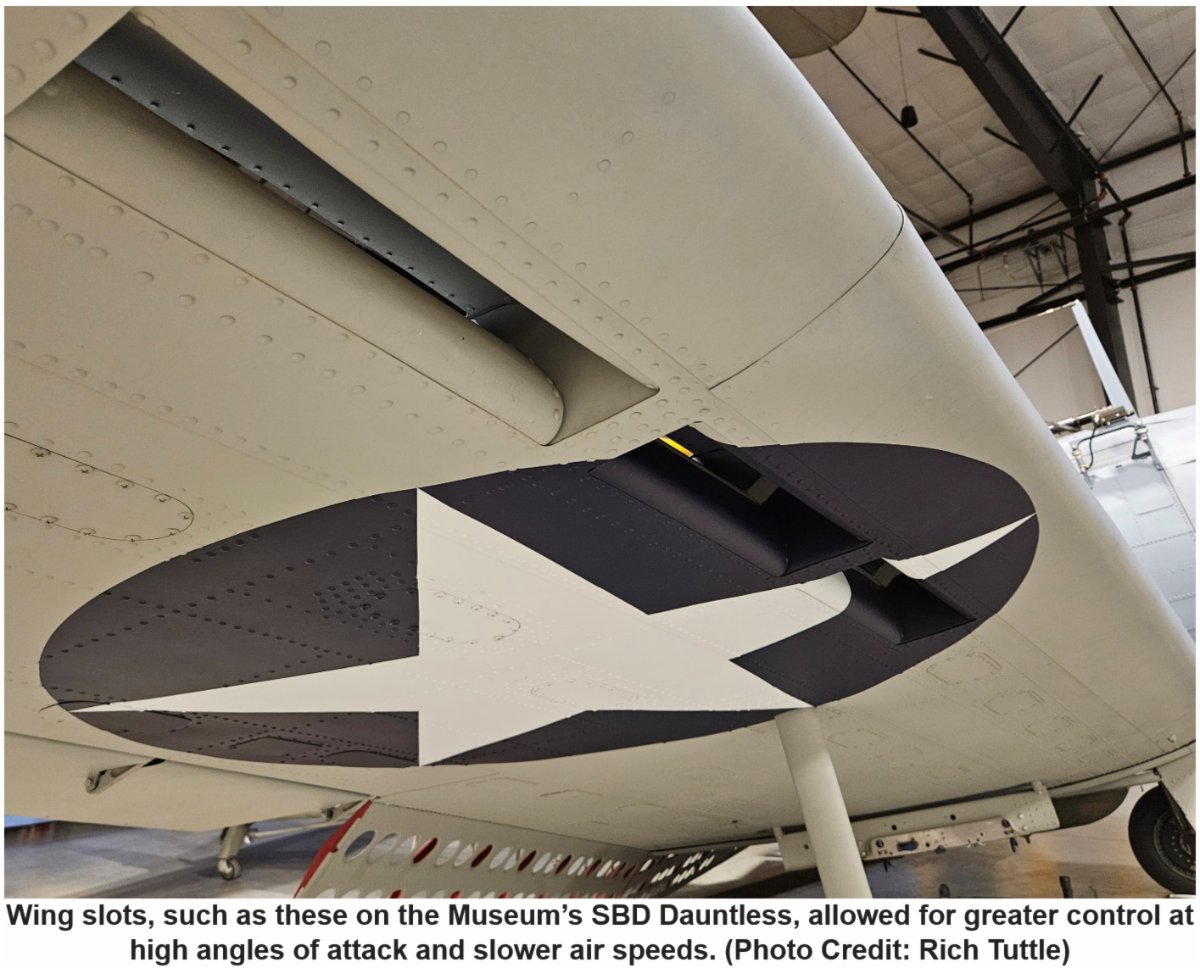

The Dauntless, for instance, has slots in its wings to ensure proper flow of air over the wing and impacts effectiveness of ailerons, even at the high angles of attack needed to get the airspeed down to just above stall.

Story Credit: Rich Tuttle

| |

Get Your 2024 Pikes Peak Regional Airshow Tickets and See the Blue Angels First Colorado Springs Appearance! | |

|

Head on over to https://www.pprairshow.org/tickets/ today to get your airshow tickets!

Attendance is limited daily and once sold out there is no admittance; tickets will not sold the day of the event, don’t procrastinate!

Tickets are sold progressively, and Saturday is getting close to being sold out!

General Admission: Saturday $47, Sunday $45

Military: Saturday $42, Sunday $40

Children (ages 4-12): Saturday $37, Sunday $35

Preferred Seating: Saturday: $85 (70% Sold out)

Preferred Seating: Sunday : $73 (50% sold out)

Canteen Experience: Saturday & Sunday: SOLD OUT

Preferred Seating:

- Prime Seating

- Private Restrooms

- Official Collectible program per order

We're expecting record airshow attendance beyond the 25K+ visitors that filled the 2022 event, especially with the first ever Colorado Springs appearance of the United States Navy BLUE ANGELS Flight Demonstration Squadron!

Remaining 2024 PPRA Preferred Seating tickets are limited; secure yours at https://www.pprairshow.org/tickets/ !

| |

|

This edition's Best Shot comes from Colin Neff, 42, of Denver, Colorado. Colin shot this photo of the U.S. Navy EA-18G Growler Demonstration Team making a slow pass in a Legacy Flight with one of the Museum's two Grumman F7F Tigercats at the 2022 Pikes Peak Regional Air Show. He used a Nikon D5100, 55-200mm telephoto lens, on Full-auto with Speed setting (5 frames/second) for the picture, and it was processed in Adobe Lightroom.

Great photo Colin!

| |

|

Send us your best shot! Here are the rules:

1. Photo entry must include name, age and city of the photographer; when the photo was taken; and what event it was taken at. For example: Kanan Jarrus, 33, Manitou Springs, May 2023 Battle of the Philippine Sea presentation. If you'd like to include any other information about your photo, please do!

2. Photo must be of a National Museum of World War II Aviation airplane, display or event

3. There's no age limit to entrants; if you're old enough to take a photo, you're old enough to enter!

4. Photo must be a good quality digital .jpeg or .png file; the higher the resolution the better

5. Photo can be horizontal or vertical format, color or monochrome, untouched or processed; get creative!

6. If photos utilize a model, an appropriate model release form must be provided

7. One entry per person, per month. Send us your best shot!

8. Deadline for entry is 12:00 p.m. MST on the 20th of each month

9. The Museum Newsletter Team (that's our smiling mugs down below) will choose the winner. Between the four of us we have something like 175 years of experience in the writing, photography and publication business; we know a good photo when we see it!

10. The winning photographer will be requested to fill out a Museum Photo Release Form and return it. There is no monetary compensation or other prize, but we think you'll be pretty proud to have your photo shown to over 4K+ newsletter subscribers!

Email your photos (and any questions) to us at museumnewsletterphotos@gmail.com. Don't forget, the entry deadline is the 20th of each month!

| |

|

Special Presentation: WASP -- Women Airforce Service Pilots

Saturday, May 18, 2024

Museum opens at 8:00 a.m.

Presentation at 9:00 a.m.

Stearman Flight Demonstration Following Presentation (Weather Permitting)

The Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP) were a brave and dedicated group of aviators who helped the U.S. to win WWII. Although they did not participate in combat directly, they did take the place of men who could and did fight in the air. These women were not military service members but civilian employees. Their training was nearly identical to that of male pilots except for the combat-related portion of instruction.

In all, 25,000 women applied for admission to the WASP training program; 1,830 were admitted and 1,074 completed the course and were assigned to operational duty at 122 bases. They flew 80 percent of all American ferrying missions; delivered 12,000 aircraft and freed up 900 male pilots for combat. In 1943 women pilots were assigned to the Training Command where they towed targets for live anti-aircraft artillery practice, simulated strafing missions, transported cargo, and served as flight instructors.

WASP eventually flew 77 types of aircraft, including the Lockheed P-38 and F-5 Lightning, Bell P-39 Airacobra, Curtiss P-40 Warhawk, Bell P-63 King Cobra, Douglas C-54 Skymaster, Curtiss C-46 Commando, Martin B-26 Marauder, Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress, and Consolidated B-24 Liberator.

On May 18, museum docent Blair Griesheim will present the story of the WASP and how their service eventually opened the way for today’s women pilots of all the military services. The presentation will begin at 9:00 a.m. and, weather permitting, will be followed by a flying demonstration of the museum’s Stearman, an aircraft used by WASP instructors to train Aviation Cadets during WWII.

Standard admission prices are in effect. The purchase of advance on-line tickets is encouraged.

Advance ticket prices are:

Adult - $17

Child (4-12) - $13

Senior and Military - $15

WWII Veterans – Always FREE!

Children 3 and Under – Always FREE!

Museum Members - Included in membership; please call 719-637-7559 or stop by the front desk to make your reservations.

And of course, parking is always FREE!

Story Credit: Museum Curator and Historian Gene Pfeffer

| |

Give Us Your Newsletter Feedback! | |

|

Do you really love an article? Did a photograph really wow you? Have a question about a story? Want to see more of a certain topic? Did something spark a memory that you'd like to share with us?

We'd love to hear your what you have to say about the newsletter; let us know by dropping the editor a message at newsletter@worldwariiaviation.org!

| |

Newsletter Staff / Contributors | |

Gene Pfeffer

Historian & Curator

| |

Rich Tuttle

Newsletter Writer, Social Media Writer, Photographer

| |

John Henry

Lead Volunteer for Communications

| |

George White

Newsletter Editor, Social Media Writer, Photographer

| | | | |