|

|

Did your car witness a crime? San Francisco Bay Area police may be coming for your Tesla

__________________________

|

|

Project Counsel Media is a division of Luminative Media. We cover the areas of cyber security, digital technology, legal technology, media, and mobile technology.

About Luminative Media: our intention is to delve deeper into issues, at greater length and with more historical and social context, in order to illuminate pathways of thought that are not possible to pursue through the immediacy of daily media. For more on our vision please click on our logo:

| |

|

Did your car witness a crime? San Francisco Bay Area police may be coming for your Tesla

Plus: U.S. police forces just love Teslas

| |

|

______________________________________________

BY:

Eric De Grasse

A member of the Luminative Media team

______________________________________________________

| |

Today's post is sponsored by Lateral Link's Bridgeline Solutions | |

|

Bridgeline Solutions has an extensive track record placing attorneys, law graduates and legal support staff in temporary and direct hire positions. It also staffs small to massive document review projects on minimal notice.

Bridgeline places a wide range of professionals, including attorneys (e.g former SCOTUS Law Clerks and AmLaw 200 Associates), paralegals, legal assistants, eDiscovery staff, privacy professionals, DEI officers, CISOs, chief operating officers, conflicts personnel, recruiters, financial personnel, project managers, and contract managers.

Through it's comprehensive network and highly refined recruitment process, Bridgeline identifies top-tier candidates who possess the skill sets and experience necessary to excel in their respective roles.

For more information, please click here.

________________________________________________

| |

|

4 September 2024 (San Francisco, CA) - I spent a good chunk of yesterday driving a Tesla around a test track. Elon might be a piece of s**t, but his car is a wonder. The Tesla's advanced sensors, cameras, and artificial intelligence to enhance safety and assist with driving tasks are simply amazing.

But later today I will test drive a Chinese auto manufacturer's EV (electric vehicle) and I'll make comparisons.

And, as usual, "the law" has made its presence known. The situation in which a car acts as a witness against its human driver (or as a witness in events in which its presence was known) in a court of law began cropping up in the legal journals as far back as 2018. This possibility became a reality due to technology embedded in modern-day vehicles that captures data prior to a crash event, or when a car is in the vicinity of a crime or other event. And it began in earnest in California when the police started using "crowdsourced data" taken from cars as an additional source of information in the fact-finding process.

There was an article in yesterday's San Francisco Chronicle about the issue vis-a-vis Teslas. The article is behind the newspaper's pay wall but I have a subscription so I did a cut & paste and the full article is below.

And, yes, to our legal eagle readers: many eDiscovery vendors are carving out a specialty on collecting data from EVs.

|  | |

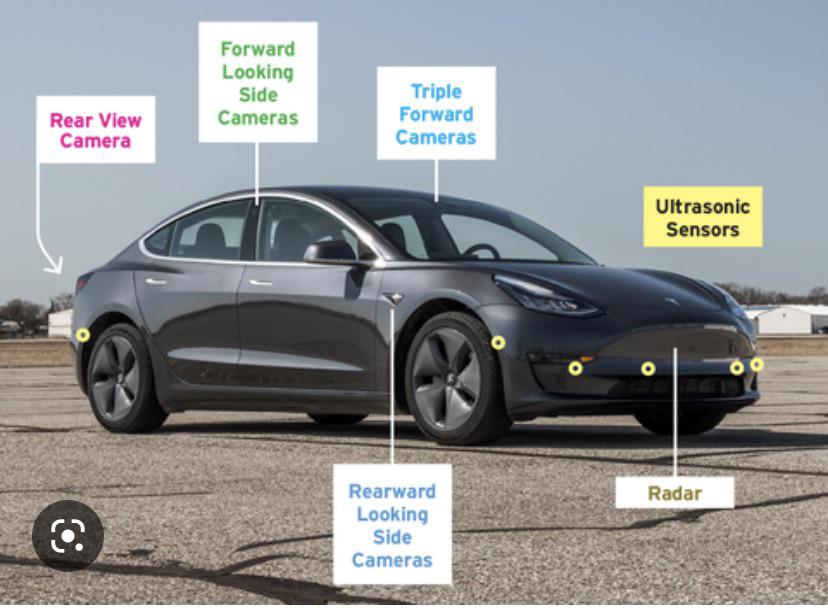

Tesla cameras show the multiple angles that are recorded around the vehicle. Police now routinely request subpoenas and warrants in investigations if they were parked anywhere near a crime scene — even if the car wasn’t involved | |

|

A Canadian tourist was visiting Oakland, California recently when he had to talk someone out of taking his Tesla from a hotel parking lot.

This was no thief. It was the Oakland Police Department. Turns out, the Tesla may have witnessed a homicide.

In Oakland and beyond, police called to crime scenes are increasingly looking for more than shell casings and fingerprints. They’re scanning for Teslas parked nearby, hoping their unique outward-facing cameras captured key evidence. And, the Chronicle has found, they’re even resorting to obtaining warrants to tow the cars to ensure they don’t lose the video.

The trend offers a window into how mass surveillance — the expansion of cameras as well as license-plate scanners, security doorbells and precise cellphone tracking — is changing crime-fighting. While few cars have camera systems similar to Teslas, that could change rapidly, especially as the technology in vehicles continues to improve.

“We have all these mobile video devices floating around,” said Sgt. Ben Therriault, president of the Richmond Police Officers Association.

Therriault said he and other officers now frequently seek video from bystander Teslas, and usually get the owners’ consent to download it without having to serve a warrant. Still, he said, tows are sometimes necessary, if police can’t locate a Tesla owner and need the video “to pursue all leads.”

“It’s the most drastic thing you could do,” he acknowledged.

In at least three instances in July and August, Oakland police sought to tow a Tesla into evidence to obtain — via a second court order — its stored video. Officers cited the cars’ “Sentry Mode” feature, a system of cameras and sensors that records noise and movement around the vehicle when it is empty and locked, storing it in a USB drive in the glove box.

The case involving the Canadian tourist happened July 1 outside the La Quinta Inn near the Oakland airport. When officers arrived at the parking lot shortly after midnight, they found a man in an RV suffering from gunshot and stab wounds. He was later pronounced dead at Highland Hospital.

Officers also noticed a gray Tesla parked in the stall opposite the RV.

“I know that Tesla vehicles contain external surveillance cameras in order to protect their drivers from theft and/or liability in accidents,” officer Kevin Godchaux wrote in the search warrant affidavit obtained by the Chronicle, noting that the vehicle was perfectly positioned to document what happened.

“Based on this information,” Godchaux wrote, “I respectfully request that a warrant is authorized to seize this vehicle from the La Quinta Inn parking lot so this vehicle’s surveillance footage may be searched via an additional search warrant at a secure location.”

Oakland police officials did not respond to a request for comment, nor did the Tesla owner back in Calgary. A source familiar with the investigation said the owner showed up as crews were loading his car onto a tow truck and intervened. When he volunteered the video, police released his vehicle.

There’s no guarantee that a Tesla will record a crime that occurs near it. That depends on factors including what mode the car is in and whether the system is triggered. But police who view Teslas as rolling surveillance security cameras aren’t taking chances.

“When you have these cars on the roads that are constantly capturing information, even when they’re parked, the police can look to them as a resource,” said Saira Hussain, a staff attorney at the Electronic Frontier Foundation who specializes in government surveillance. “That obviously puts third parties — people who are not involved at all — in the crosshairs of investigations.”

Similar issues have come up with self-driving cars now on the road in San Francisco and other cities, which are also equipped with sophisticated video capability, Hussain noted. But in those cases, police subpoena the tech company — typically Waymo — because it owns the cars and the data. Tesla drivers, by contrast, get served individually because they control their own camera footage.

In recent years, Tesla camera footage has played a variety of roles in police investigations, most commonly offering evidence after crashes but also documenting crimes perpetrated on a car’s owners or identifying a burglar who enters a car. The use of court orders related to crimes that occur near a Tesla appears to be a newer wrinkle.

On July 13 in Oakland, an argument between several people outside a beauty supply shop at 40th Street and Telegraph Avenue escalated when five of them drew guns and began shooting at each other, police said, killing a 27-year-old woman.

Oakland police officer Roland Aguilar obtained a search warrant to tow three vehicles, including a Tesla Model X with Kansas plates, writing in a court affidavit, “This video could provide valuable information relevant to the ongoing investigation.”

Weeks later, two men were charged with murder and a raft of other felonies in connection with the shooting. Probable cause declarations for their arrests referred to “high-definition quality surveillance footage” of the homicide, without specifically mentioning the Tesla. Police had also gathered video from a nearby market, the affidavit said.

Another search warrant affidavit from Oakland police described an incident on Aug. 12, in which the city’s gunfire detection system prompted officers to rush to 13th and Center streets in West Oakland. There, they found a man with a gunshot wound to the head in the back seat of his girlfriend’s Tesla. The girlfriend, also in the car, gave officers a “partial statement,” the affidavit said. Officers took a bloody cell phone she was carrying and allowed her to leave.

Though officers found no weapons inside the Tesla, they towed it as evidence, believing its cameras may have recorded the crime, according to the affidavit. Paramedics drove the victim to Highland Hospital, where he was listed in critical condition. No arrests have been made in the case.

Tesla video could be crucial as well in prosecuting a young man over a homicide that occurred in January in San Jose, said Sean Webby, a spokesperson for the Santa Clara County district attorney.

Webby said the Tesla was “not associated with either the suspect or the victim,” but happened to be parked nearby, he said, when the driver of an Infiniti intentionally ran over an already wounded man and then kept going.

| |

|

From Wired Magazine

15 August 2024

At a rally this past April in Michigan, surrounded by a cadre of law-enforcement officials, Donald Trump suddenly began railing against electric cars. President Joe Biden’s decision to support EVs, he decried, “is one of the dumbest I’ve ever heard.” Minutes later, he was back to praising the sheriffs behind him: “We have to get law and order back. These are the best people in the world,” he said to a smattering of applause.

Support for law enforcement and skepticism of electric cars both abound on the right. Police officers are more likely to identify as Republican than the communities they serve, and their unions widely endorsed Trump in 2020. Meanwhile, the Americans buying electric cars tend to be Democratic. And yet, more and more law-enforcement officers seem to be taken by EVs. When they “get into and experience the [electric] cars firsthand themselves,” Tony Abdalla, a sergeant with the South Pasadena Police Department, told me, “they’re like, Okay, I think I get it now.”

Last month, South Pasadena’s police department became the first in the country with a fully electric police fleet, replacing all of its gas-powered vehicles with 20 Teslas. Four officers, after test-driving Teslas for the department, have already bought one for personal use, Abdalla, who leads his department’s EV-conversion project, told me. South Pasadena is one among a growing number of law-enforcement agencies that are electrifying their fleets. About 50 miles south, the Irvine Police Department just became likely the country’s first to purchase a Tesla Cybertruck. Departments in at least 38 states have purchased, tested, or deployed fully electric cars. Electric patrol cars are not yet legion and in many cities are likely less common than EVs among the general population, but their ranks are growing. They now prowl the streets in Eupora, Mississippi; Cary, North Carolina; and Logan, Ohio.

The nation’s switch to battery-powered police cruisers isn’t only, or even primarily, about the environment. In many cases, they are proving to simply be the best-performing and most cost-effective option for law enforcement. Police departments require vehicles that have rapid acceleration and deceleration; space for radios, sirens, and other special equipment; and extreme reliability for 24-hour emergency responses. When the South Pasadena police first looked into electrification, in the mid-2000s, no EVs on the market could handle the heavy workload that law enforcement demands. The last thing any police officer needs is to worry about their car running out of charge mid-shift. When Tesla unveiled the Model Y in 2019, Abdalla said, it “perked us up.” The model’s range, safety, and power made it the first EV that appeared potentially suitable for the department.

Five years later, the cars have gotten much better. New EVs can regularly drive upwards of 200 or 300 miles per charge, plenty for many officers. Multiple companies help modify Teslas with the necessary equipment to turn them into patrol cars, and both Ford and Chevy market EVs specifically for police use. And from a performance perspective, EVs are appealing for law enforcement because they are typically more powerful than gas-powered cars. The acceleration can verge on the absurd—an electric Hummer pickup truck, which weighs nearly 10,000 pounds, can go from zero to 60 miles per hour about as quickly as a Formula 1 race car. The reason is simple: Whereas combustion engines have to transfer energy from a series of explosions through the transmission and then to the wheels, electric motors instantly begin spinning the tires.

An annual vehicle test by the Michigan State Police precision-driving unit, which is used by departments across North America to gauge a car’s suitability for police use, found last year that the Chevy Blazer EV and the Ford Mustang Mach-E accelerated from zero to 100 miles per hour in roughly 11 seconds, about half the time of many popular gas-powered police cars. On a highway patrol, improved acceleration means catching up to other cars more quickly and risking fewer accidents, says Nicholas Darlington, the Michigan State Police precision-driving unit’s commander. If a suspect is fleeing in a high-end EV, a gas-powered pursuit vehicle might just not be able to catch up: There are numerous videos of police cars struggling to keep pace with Teslas on real and controlled roads.

An EV is typically more expensive up front than a gas-powered car, but police departments offset those costs by not needing to fuel up. The South Pasadena PD expects to save $4,000 a year per EV on fuel alone, Abdalla said. EVs also require less maintenance than gas cars do, compensating for higher sticker costs. After factoring in maintenance and other savings, the operational costs of the city’s Teslas could be half the price per mile driven. New York City, which has one of the largest police fleets in the world, now has roughly 200 EVs, and citywide has “achieved probably 60 to 70 percent maintenance savings in our existing electric fleet,” Keith Kerman, NYC’s chief fleet officer, told me. The most expensive and time-consuming repairs, combustion-engine and transmission replacements, are wholly unnecessary for EVs, he added, meaning the cars can more consistently stay on the road and free up mechanics.

Todd Bertram, the police chief in Bargersville, Indiana, told a local news site that the department’s 13 Teslas are leading to roughly $80,000 in savings on fuel costs, freeing the agency up to hire two additional officers. “For us, it was primarily an operational decision,” Abdalla said. “We got a much better-performing fleet that cost significantly less to maintain and fuel. It saves taxpayers money.”

EVs don’t make the best police cars in every situation. Some departments that have piloted Teslas have determined that they are too small for regular police work. Range is another concern: South Pasadena is a relatively small municipality in which officers are unlikely to drive more than 60 miles in any given 12-hour shift, Abdalla told me. In New York City on a triple shift, an EV battery’s range might not cut it, which is why the NYPD operates more than 2,000 hybrids, Kerman told me. Chargers are much slower than refueling a gas tank, and there are still not enough of them. EVs may not always be practical for state troopers or highway-patrol officers, who may have to drive long distances over roads without much of an EV-charging infrastructure.

As more officers are seen patrolling highways and parks, making traffic stops and arrests, and idling on street corners in Teslas, electric pickup trucks, and battery-powered SUVs, more Republicans may give EVs a chance. “Given the high trust Republicans have in law enforcement, it’s possible that those who were once skeptical of EVs could have a more favorable impression of these products once they see law enforcement using them,” Mike Murphy, who runs the EV Politics Project, an advocacy group dedicated to getting Republicans to adopt EVs, told me over email.

That will not be the case everywhere—if police cars aren’t labeled as electric, for instance, people may not notice them, Loren McDonald, an EV consultant, told me over email. In some places, the effect of electric police cruisers might even dissuade more drivers: “Pushing for EVs using climate-change arguments … would further alienate GOP politicians and voters who have a polarized and entrenched view on climate change,” Murphy said.

Right now, electric cars might actually be more divisive than law enforcement. Some recent polling suggests that Republicans and Democrats may be more closely aligned in their confidence in the police than in how they view EVs. GOP politicians might even prevent police departments, along with other government agencies, from buying EVs, as Republican legislators attempted to do in Kentucky earlier this year. Defunding the police is already a controversial idea; defueling the police may turn out to be as well.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

Note to readers: Trump has since changed his tune. Having Musk's support he has pledged, if elected, to buy Tesla Cybertrucks for the U.S. military and subsidize the purchase of Teslas and Cybertrucks by U.S. police departments.

| |

|

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

For the URL to this post, please click here.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

| | | | |