By Jefferson Scholar-in-Residence

Dr. Andrew Roth

| |

|

‘Americans & Their Games’ (Part II)

Freedom’s Faultlines: Indigenous Americans &

Sports in American History

| |

|

What are lacrosse’s origins?

What, if any, positive impact have sports played in assimilating the Indigenous people (Native Americans) into American society?

How does the history of sports in American society track women’s and African Americans’ quest for civil rights?

How have sports served as a portal into American society for generation after generation of immigrants?

Beginning with this installment of “Americans & Their Games”: Sports in American History and Culture , the next several Book Notes will try to answer those questions about the world’s experience of American society through the lens of sports as we explore Indigenous people (Native Americans), African Americans, women of all hues and ethnicities, and immigrants.

***

| |

|

Just as elsewhere, sports among the indigenous people of the Americas are ancient. Versions of ring and pole games are found all over the world. Native American peoples played multiple variations of it. The Mandan people, who have lived for centuries in what is now North and South Dakota, played a version called Tchung-kee. According to American artist George Catlin, who observed the Mandan in 1832:

This game is decidedly their favourite amusement, and is played near to the village on a pavement of clay, which has been used for that purpose until it has become as smooth and hard as a floor. … The play commences with two (one from each party), who start off upon a trot, abreast of each other, and one of them rolls in advance of them, on the pavement, a little ring of two or three inches in diameter, cut out of a stone; and each one follows it up with his tchung-kee’ (a stick of six feet in length, with little bits of leather projecting from its sides of an inch or more in length), which he throws before him as he runs, sliding it along upon the ground after the ring, endeavouring to place it in such a position when it stops, that the ring may fall upon it, and receive one of the little projections of leather through it. [1]

| |

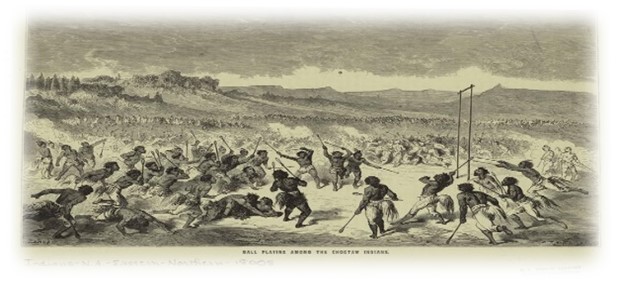

|  | In addition to ring and pole games, Indigenous Americans excelled at archery and horse and foot racing contests. But the preeminent Native American game was and remains lacrosse. Although the picture accompanying this text illustrates a ball game similar to lacrosse played by the Choctaw Indians, no one knows the game’s origins. It has been known by many names, including “Creator’s Game, Baggataway, and ‘little Brother of War’ or Tewaaraton.” [2] Lacrosse, however, is most intimately associated with the Indigenous people of the northeastern woodlands, in particular the Haudenosaunee – an Iroquoian speaking people who the French called the Iroquois League and the English the Five Nations. The Haudenosaunee, which means the “people of the long house,” live in New York state and Quebec and Ontario, Canada along New York’s northern border. From east to west, the Five Nations of the Iroquois (the Haudenosaunee) are the Mohawk, the Oneida, the Onondaga, the Cayuga, and the Seneca. When the Tuscarora emigrated north from the Carolinas, they were absorbed into the Haudenosaunee and the confederacy became known as the Six Nations.

The earliest known team sport in North American history, among the Haudenosaunee, the first lacrosse game dates to approximately 1100 A.D. Lesley Kennedy says, “The early versions of lacrosse matches played by Native American nations included 100 to 1,000 men or more using wooden sticks, sometimes with net baskets or pockets attached, and small, deer hide-wrapped balls. Deer sinew formed nets. Borderless fields could span miles, and games could last days.” [3]

French Jesuit missionary Jean de Brebeuf, who was among the first Europeans to see a lacrosse “game,” named it “lacrosse” because the stick with a leather pocket at its end resembled a Bishop’s staff or crosier, which the French called a “crosse”; hence, an individual “stick” was “la crosse” anglicized to lacrosse. [4] [5] The game has many names in Indigenous people’s culture; among the Six Nations the Onaondaga call it Dehuntshigwa’es (“men hit a rounded object”) and the Mohawk know it as Begadwe and/or Tewaaraton (“little brother of war”). The NCAA (National Collegiate Athletic Association) award to the outstanding college men’s and women’s lacrosse player is called the Tewaaraton Award. The NCAA received permission from the Mohawk Nation Council before using the name. [6] [7]

In Part One of “Americans and Their Games,” we discussed that in many ancient cultures sports have religious origins and that in contemporary American culture some observers assert sports have acquired almost a religious character in the intensity of their followers. Lacrosse’s origins in Haudenosaunee culture speak to this religious character. Neal Powless, a member of the Onondaga Nation and a former professional lacrosse player, notes that in one version of the Haudenosaunee creation myth “a young woman and a chief, living in the Sky World, or a multiverse space, must marry to save their universe from destruction. But her attention is drawn to a lacrosse player who later dives through a hole torn in the multiverse to save her, and they mate before she lands on Earth.” [8] So, as Powless continued, “lacrosse is part of that story of our creation, of our identity, of who we are.” [9]

In American sporting culture, until recently lacrosse was a niche sport played in Native American communities and more generally along the East Coast of the United States. Since the 1990s, however, it has become the fastest growing high school and college sport. Its growth has been strongest in suburban schools, where it has achieved “designer sport” status. In the Erie area, it flourishes at McDowell, Fairview, and Cathedral Prep. The Mercyhurst University men’s team won the 2011 NCAA Division II national championship. At the Division I collegiate level, it is still dominated by East Coast schools, with Maryland the 2022 national champions. Since 2000, Johns Hopkins University, Yale University, Syracuse University, Princeton University, and others have dominated. Since 1971, only one school west of the Allegheny Mountains has won a national championship – the University of Denver in 2015. [10]

Regardless of lacrosse’s newly earned status as the middle- and upper-middle class sport of choice, one of the best men’s lacrosse teams in the world remains the Haudenosaunee Nationals Men’s Lacrosse Team. Founded in 1983 by the Grand Council of the Haudenosaunee as the Iroquois Nationals, the team changed its name to Haudenosaunee Nationals in 2022. [11] The Haudenosaunee are currently the third-ranked men’s lacrosse team in the world. The Haudenosaunee took the Bronze Medal at the World Championships in 2014 and 2018. It should come as no surprise that No. 1 and No. 2, respectively, are the United States and Canadian men’s teams. They will all meet again in the 2023 World Championships in San Diego.

Athletic quality aside, garnering more headlines has been the Haudenosaunee Nationals’ passport issues. Using their Haudenosaunee passports, in 2010 they were denied entry to England prohibiting them from competing in the 2010 World Championships. The passport issue raised its head again for the 2018 championships in Israel when only the intervention of the Federation of International Lacrosse and Canada enabled them to enter Israel.

| |

|

In use since 1923, the current Iroquois passport evolved from negotiations in 1977 with the U.S. State Department, Canada, Britain, and other countries. Since it involves the sovereignty issue regarding the legal status of Indigenous tribes within the United States, the passport issue remains a muddle. The sovereignty issue is beyond the scope of a mere Book Note, but its essence remains the unsettled question of whether the Indigenous nations are sovereign countries within the United States; that is, do they have tribal sovereignty and the inherent authority to govern themselves? Or are they, as the U.S. government recognizes them, domestic dependent nations as defined by the United States legal system that determines the relationship between tribal governments and the federal and state governments?

If sports are a lens into American history and culture, then the Haudenosaunee passport issue opens up the fraught question of the relationship between the Indigenous people and the larger American society. That question spawns a series of other questions:

Are the Indigenous people a conquered people subsumed into the larger American whole?

Or, are they a people with whom the larger American society has reached a state of détente each seeking to accommodate the other?

Or, are the Indigenous tribal nations independent sovereign countries?

Or, are they members of the United States?

Or, are they both?

In Indigenous culture, which of course is not homogeneous, there are numerous Indigenous cultures, an assimilated part of American culture, or are they distinct and separate cultures, or are they both? Are Indigenous people citizens of their own autonomous tribal nations, or are they American citizens of the United States, or are they both?

As culturally and legally complex as it is, the question of citizenship is comparatively easy to answer. Since the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924, all Indigenous people are citizens of the United States. Not all Indigenous tribal leaders supported American citizenship, fearing it would erode tribal integrity and ultimately survival. Since many Indigenous tribal nations hold land in common and require that their members maintain their tribal citizenship, Indigenous people are granted dual citizenship – they are both citizens of their tribal nation and the United States.

Even more than the legally snarled citizenship question is the emotionally charged question of cultural assimilation. The question is as old as the history of the interaction between Europeans and the Indigenous people of North America. In broad strokes, from the European perspective there were three courses of action: either eradicate the Indigenous people (a polite way of saying ethnic cleansing); or accommodate them by setting aside land for them but essentially living separately (the reservation system); or assimilate them into Euro-American culture. From the Indigenous people’s perspective, the issues were similar if inverted: fight to the end risking extinction; or make a separate peace and retreat to tribal enclaves (essentially the reservation system); or make peace with the Europeans and assimilate into Euro-American culture. On both sides, there were those who advocated for each of these positions.

In the end, the result was a bloody muddle of all three.

Sports shed a light on two facets of the issue of cultural assimilation. Using the profound and familiar metaphor developed in Part I of this series, we will look at the profound issue of the Indian School Project and the familiar (popular culture) issue of sports teams using Indigenous names and images as sports teams’ nicknames, logos, and mascots.

| |

|

The topic of Indian Boarding Schools dwarfs what a simple Book Note can cover. It is also a topic about which the vast majority of Americans know very little. The primary focus of the Indian Boarding Schools was to “civilize” or “assimilate” Indigenous children into Euro-American culture. In the late-20th century, this came under intense criticism, but eschewing that anachronistic judgment, stepping back and trying to understand what U.S. Army Lt. Richard Pratt, who founded the Carlisle School, and others thought they were doing provides a more balanced insight. Misguided as they might have been from a 21st century perspective, they sought to find an alternative to eradicating the Indigenous people.

They wanted to assimilate the Indigenous people into Euro-American culture. Pratt’s motto was “Kill the Indian, save the man.” They taught the Indigenous children English, industrial and other skills, and how to live and function in Euro-American society. Their methods were harsh. Their results were mixed. Over 10,000 children from 140 tribes attended Carlisle between 1879 and its closure after World War I in 1918. For a more complete treatment of the subject of the Carlisle Indian School from the perspective of the Indigenous people visit the Carlisle Indian School Project’s website.

What has all of this to do with sports?

Ironically enough, it has been sports historians’ interest in the accomplishments of the Carlisle Indian School’s football team that brought attention back to the larger question of forced assimilation, for in the early 20th century the Carlisle Indian School fielded one of the greatest intercollegiate football teams of all-time.

From 1893 until 1917, the Carlisle Indians won 64.7% of their games. They invented the hand-off fake and the overhand spiral throw – the forward pass. Coached by the legendary Glenn “Pop” Warner, who would later win national championships at the University of Pittsburgh and Stanford, during the first decade of the 20th century Carlisle competed against and beat the major intercollegiate powers of the day – Harvard, Penn, Cornell, and Army. In 1907, before 20,000-plus fans at Franklin Field in Philadelphia, Carlisle blasted the powerful Penn team, 26-6. In 1911, in one of the greatest upsets in college football history, Carlisle defeated the era’s greatest powerhouse, Harvard, 18-15. Jim Thorpe scored all of Carlisle’s points. In 1912, Carlisle defeated West Point, 27-6.

Yes, 22 years after the last Indian/Army battle at Wounded Knee, the Indians beat the cavalry, 27-6.

The 1912 West Point team featured nine future generals, including President Dwight D. Eisenhower and General of the Army Omar Bradley. On the Carlisle side were future professional football players Jim Thorpe, Pete Calac, and Joe Guyon. Grantland Rice, one of the first of the great sportswriters, was quoted as saying, “I believe an All-American, All-Indian Football team could beat the All-Time Notre Dame Team, the All-Time Michigan Team, or the All-Time anything else. Take a look at a backfield like Jim Thorpe, Joe Guyon, Pete Calac, and Frank Mount Pleasant.” [12]

| |

|

Thorpe himself is arguably the greatest athlete of the 20th century. A Sauk and Fox Indian from Oklahoma, Thorpe was a college All-American football player on Walter Camp’s teams of 1911 and 1912; at the 1912 Olympics he won the Gold Medal in the decathlon and the pentathlon; from 1913-1919, he played Major League Baseball for the New York Giants and Cincinnati Reds; he played professional football from 1919-1925 for the Canton Bulldogs, NFL champions in 1922; he was a founder and first president of the American Professional Football Association (which evolved into the NFL); he also excelled in basketball, boxing, lacrosse, swimming, and ice hockey. Thorpe was the first person elected to the Professional Football Hall of Fame. To this day the Most Valuable Player trophy in the NFL is the Jim Thorpe Trophy.

| |

|

Native Americans have continually distinguished themselves in sports. A member of the U.S. Marine Corps, Billy Mills, a member of the Ogala Lakota people, was the first and remains the only American to win the Olympic Gold Medal in the 10,000 meters (10K) race. Mills attended the Haskell Indians Nations University in Lawrence, Kansas before attending the University of Kansas, where he was a three time All-American in cross country. Still active in the fight for Native American rights, Mills was co-founder of “Running Strong for American Indian Youth,” an organization that helps Native Americans meet their basic needs. As Andrew McGregor says, “Mills is widely known in within the Native American community as an inspirational Olympic hero, activist, and advocate for Indian Youth.” [13]

| |

|

Mills also has spoken out against the use of sports teams using Indian themes and images as nicknames, logos, and mascots. He particularly worked against the Washington Commanders’ former use of the nickname “Redskins.” Of all the “Indian-themed” names used to identify sports teams, amateur, high school, collegiate, and professional, “Redskins” was the most offensive. Most Americans didn’t know, many still refuse to know, that it signified, as Mills points out, the Indigenous people’s own holocaust that saw the demise of 12 to 23 million Indigenous Americans after the arrival of Europeans. As Mills himself said, “Redskins is among the most vulgar for us. …In Minnesota and some other states, the tribes whose lands were in those states now, there were bounties paid. X number of dollars if you brought in a female scalp of a Redskin. X number of dollars if it were a child. X number of dollars if it were an adult man.” [14]

The use of Indian names and themes for sports mascots is a contentious issue. As someone who was a Cleveland Indians fan since before I knew how to read, I came to understand the issue late. But upon reflection, the myth that the team was named after Louis Sockalexis, a Penobscot Indian who played for the Cleveland baseball team when it was known as the Blues or Naps, notwithstanding that there is some substance to the story, is irrelevant. It is not for me or you to decide if something we utter is offensive; it is for the person to whom it is said or the person about whom it is said to determine. If Americans of African descent say the N-word uttered by a white person is offensive, then I don’t use it.

It’s just that simple.

Similarly, if Indigenous Americans say the use of their name, their likeness, or images and objects derived from their culture is offensive, then it is our responsibility to refrain from using them. It is really just that simple. The name “Redskins” always struck me as marginally offensive, but when I learned what it actually meant – literally a scalp carved from a person, the most valuable of which were torn from either a woman’s head or pubic area – then the discussion ended. [15]

As for me and the team formerly known as the Cleveland Indians, I am now an ardent fan of the Cleveland Guardians. The name first struck me as bland, but I am now all-in and proudly support the Guards. In fact, knowing that Bob Hope’s father was one of the stonemasons who carved the figures of the Guardians of Traffic on the Carnegie-Lorain Bridge, I now say “where there’s Guardians, there’s hope.”

Sports, as they have since time immemorial, still thrive in Indigenous American culture. You can attend the North American Indigenous Games in Halifax, Nova Scotia this July 15-23; you can learn more about the history of Indigenous Americans and sports at the North American Indigenous Athletics Hall of Fame at Athlete | North American Indigenous Athletic Hall of Fame (naiahf.org) or you can visit the American Indian Hall of Fame on the campus of Haskell Indian Nations University in Lawrence, Kansas.

If the essence of the American story is the ever-increasing inclusiveness of the “We” in “We the People,” then the story of the first Americans as revealed by their experience in sports in American society starkly suggests that the issues of sovereignty, accommodation, and assimilation still remain unresolved. How to do that challenges us all, particularly in an age of white nationalists’ calls for exclusion, but meet that challenge we must.

Next week – “Americans and Their Games: The African American Experience.”

| |

-- Andrew Roth, Ph.D.

Scholar-in-Residence

The Jefferson Educational Society

This content is copyrighted by the Jefferson 2022.

| |

|

Intro Photo Credits

“Americans & Their Games collage” created by A.Roth roth@jeserie.org.

“Tchung-kee, a Mandan Game Played with a Ring and a Pole” at Smithsonian American Art Museum available at Tchung-kee, a Mandan Game Played with a Ring and Pole | Smithsonian American Art Museum (si.edu) accessed May 20, 2023 .

“Ball Playing Among the Choctaw Indians” by Gustave Dore at The New York Public Library Digital Collections available here accessed May 20, 2023.

“Haudenosaunee Passport” at Wikimedia Commons available at File:Iroquois passport.png - Wikimedia Commons accessed May 21, 2023.

“Carlisle Indian School logo” at Wikimedia Commons available at File:Carlisle Indian School Logo.png - Wikimedia Commons accessed May 21, 2023.

“Jim Thorpe, Canton Bulldogs uniform” at Wikimedia Commons available at File:Jim Thorpe Canton Bulldogs 1915-20.png - Wikimedia Commons accessed May 21, 2023.

“Billy Mills and Mohammed Gammoudi, 1964” at Wikimedia Commons available at File:Billy Mills and Mohammed Gammoudi 1964.jpg - Wikimedia Commons accessed May 21, 2023.

“Billy Mills” at Global Sports Matters available at Olympic legend Billy Mills says 'no justification' for Washington's NFL nickname - Global Sport Matters accessed May 21, 2023.

End Notes

-

Catlin, George, “Letters and Notes,” v. 1, #19, 1841 quoted at “Tchung-kee, a Mandan Game Played with a Ring and a Pole” at Smithsonian American Art Museum available at Tchung-kee, a Mandan Game Played with a Ring and Pole | Smithsonian American Art Museum (si.edu) accessed May 20, 2023

-

“Brief Origin of Lacrosse” at Edward H. Nabb Research Center, Salisbury University available at Brief Origin of Lacrosse · Native Americans Then and Now · Nabb Research Center Online Exhibits (salisbury.edu) accessed May 20, 2023.

-

Kennedy, Lesley. “The Native American Origins of Lacrosse” at History.com available at The Native American Origins of Lacrosse (history.com) accessed May 20, 2023.

-

Claydon, Jane, ed. “Origin and History: Origins of Men’s Lacrosse” at World Lacrosse available at Origin & History | World Lacrosse accessed May 20, 2023.

-

Derivation of lacrosse compiled from entries at Microsoft Translator re English “crozier” to French “crosse”; at “crosier” at Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia available at Crosier - Wikipedia; and at “Brief Origin of Lacrosse” at Edward H. Nabb Research Center, Salisbury University available at Brief Origin of Lacrosse · Native Americans Then and Now · Nabb Research Center Online Exhibits (salisbury.edu) accessed May 20, 2023.

-

“Five Things You Didn’t Know About Lacrosse” at Rocky Top Sports World available at 5 Things You Didn’t Know About the History of Lacrosse (rockytopsportsworld.com) accessed May 20, 2023.

-

“Tewaaraton Award: History of the college lacrosse honor” at NCAA available at Tewaaraton Award: History of the college lacrosse honor | NCAA.com accessed May 20, 2023.

-

Kennedy, cited above.

- Ibid.

-

“Men’s Lacrosse Championship History” at NCAA available at DI Men's Lacrosse Championship History | NCAA.com accessed May 20, 2023.

-

“Our History” at Haudenosaunee Nationals Lacrosse available at Our History – Haudenosaunee Nationals accessed May 20, 2023.

-

Cited without substantiating source in “Pete Calac” at Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia available at Pete Calac - Wikipedia accessed May 21, 2023.

-

McGregor, Andrew, “Review of Redskins: Insult and Brand” in Sport in American History (6 March 2016) available at Review of Redskins: Insult and Brand | Sport in American History (ussporthistory.com) accessed May 21, 2023.

-

Daffron, Brian. “Billy Mills: Redskins Name Calls to Mind ‘Our Own Holocaust’” at ICT available at Billy Mills: Redskins Name Calls to Mind 'Our Own Holocaust' - ICT News accessed May 21, 2023.

-

Bechtoldt, Max, “Olympic legend Billy Mills says ‘no justification’ for Washington’s NFL nickname” at Global Sports (November 21, 2018) available at Olympic legend Billy Mills says 'no justification' for Washington's NFL nickname - Global Sport Matters accessed May 21, 2023.

| |

JES Mission: The Jefferson was founded to stimulate community progress through education, research, and publications. Its mission also includes a commitment to operate in a nonpartisan, nondenominational manner without a political or philosophical bias. As such, the Jefferson intends to follow the examined truth wherever it leads and is neither liberal nor conservative, Democratic nor Republican in philosophy or action. Our writers’ work reflects their own views. | | | | |